Summary

Blinded by the Light is a musical coming-of-age story that’s truly timeless, saying profound things about life and struggles in 1980s England that transcends its setting and hits us in the here and now.

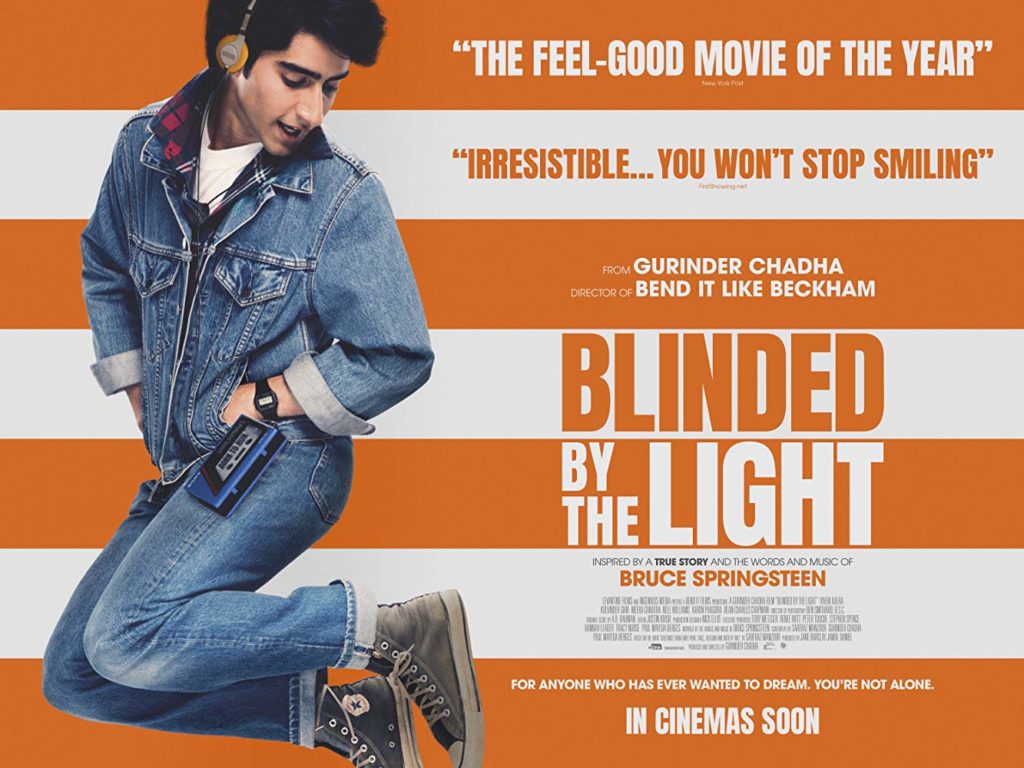

Director Gurinder Chadha, along with writers Paul Mayeda Berges and Sarfraz Manzoor (on whom Blinded by the Light is based), tell the story of Javed Khan (Viviek Kalra) as he grows up in Luton, in the southeast of England. It’s a tale of growth, of music, of words, of love, of life, and it’s utterly universal – infused with the music of Bruce Springsteen.

Javed is the son of Pakistani immigrants Malik (Kuvinder Ghir) and Noor (Meera Ganatra), and he struggles furiously to navigate his multifaceted identity. He’s ethnically Pakistani and religiously Muslim in a traditionally Caucasian Christian nation. The 1980s saw a rise in fascism, which meant that his family was encircled by people who looked down on them. More than that, his father has no intention of seeing his son integrate into their adopted society. Moreover still, Javed is a teenager, attempting to sort out his impending university, his exams, his best friend, his girlfriend, and his pursuit of writing. In his words, Javed wants to: “Make loads of money. Kiss a girl. Get out of here.” The person who helps him make sense of all the conflicting aspects of his worldview: The Boss himself, Bruce Springsteen.

Javed runs into a fellow outsider, a Sikh student at his school, Roops (Aaron Phagura). Roops tells him about Springsteen: “The Boss is the direct line to everything true in this sh–ty world.” And with that, Javed’s world changes.

Bruce helps unleash Javed’s creative dreams, affirming that his pain is real. Music helps him to forget the world around him, but also to make sense of it. Bruce doesn’t speak for Javed, but his words echo Javed’s experience and help him figure out how to speak for himself. It gives Javed the impetus to pursue his writing, to ask out a girl, to dream, to hope.

From a young age, Javed has kept diaries and written poetry, but he’s never thought anything of it because his father would never allow him to pursue writing as a career. He’s simply supposed to work at something respectable and stable – maybe a lawyer – and provide for his family. Yet children are told to dream, to pursue their passions. This fuels his identity struggle. His father tells him: “You will always be Pakistani. You will never be British.” Meanwhile, neo-fascists, led by the National Front (the NF) are scrawling “Pakis get out” and chasing him around the estate. Kids are peeing in the Pakistani families’ mail slots and shouting, “Smelly smelly Pakis.” This isn’t isolated — it’s so common that Javed’s family friends just keep plastic beneath the mail slot. Javed’s community is totally isolated, further reinforcing his father’s words. Yet he yearns to escape, and Springsteen provides him with a picture of another world, speaking the language of angst, but fighting against that oppression he feels.

Javed just wants to write, to say something, to shout truth and find meaning into the oppressive void. He finds support from his English teacher Ms. Clay (Hayley Atwell), who tells him to write more, that he has a responsibility to make himself heard. His writing affects those around him; its importance rings true in the midst of the prejudice. “You must write more and get your message out.” He needs to counter people like the NF, who are marching and spreading bile and hate throughout England. Springsteen’s music provokes Javed to write about who he is, who he hopes to be, even who his father wants him to be. Javed’s father tells him he’s supposed to keep his head down and not be noticed, but Javed has a voice that cannot be silenced.

The film speaks of being blinded by the light — straight from The Boss himself. This blindness pervades the film: blindness to others’ needs, to family’s wishes, to the world around us. The British Pakistani community’s struggle against the NF bears powerful echoes to today. “No one in America cares where you’re from.” He speaks about the American dream as something he can attain, with stars in his eyes. And he finds it there, in New Jersey. I feel a little pang because this movie could be set entirely in the US today. The UK of the 80s saw fascist marches against immigrant families — not distinguishing between legal or illegal — with “Keep Britain White” banners. We’re seeing all too similar things, here and now in the United States. The film portrays wholesale blind(ed by the light) people who see blanket depictions of all people who appear different than the theoretical norm. And yet Springsteen speaks to the struggle of the Everyman; he speaks about daring to dream, to hope, that all people deserve respect.

Viveik Kalra gives a raw performance which I wish was a bit more polished. The supporting cast is solid overall, but it feels like some pieces of the plot and cast are dropped and then picked up at random.

Stylistically, the portrayal of the music varies wildly, to equally varied effect. The music shifts from diegetic to soundtrack, while lyrics often appear as superimposed text to projected words on buildings. Sometimes there are dance numbers and sometimes a fantasy sequence. I really wish they’d embraced the musical part just a bit more because those moments were the best – it lent both a visual and aural unevenness to the film that, at times, felt disconcerting.

We’ve had a glut of music-oriented films of late — but not all created equal. They’re not all actual musicals, but music plays such a central part, beating at the heart of so very many people. Blinded by the Light speaks to this universality of music as a means of moving people. Blinded by the Light isn’t as slick as Yesterday, nowhere near the heart of A Star is Born, but with much much more heart than Bohemian Rhapsody, and less musical fantasy than Rocketman.

Blinded by the Light is meaningful and deeper than you’d think, with a message that transcends its 1980s British setting, hopefully speaking to people around the world today. It’s got its flaws—it’s at times too saccharine, often oddly edited, with some jumps in plot logic, and uneven performances. However, it’s still well done overall and, like the best music-based films, makes me want to just switch on its soundtrack. Moreover, I’ve been chewing on its message for hours, hoping that others will do the same.