Summary

A visceral crime film that gives us a powerful look at the urban drug trade and the bleak despair of escaping your circumstances, while exploring race relations between the police and the community they serve.

To honour the success of BlackKklansman, we have taken a look back at Clockers, a lost in the shuffle Spike Lee Joint that was ahead of its time.

Director Spike Lee directed a crime film that was hardly noticed in 1995; if it were released today, it would be considered contemporary.

Before David Simon’s groundbreaking HBO series The Wire (but after his true-crime classic Homicide: Life On The Killing Streets), produced by Martin Scorsese (who was set to direct before deciding on Casino), and adapted from Richard Price’s masterful novel (who went on to write several episodes of The Wire and even played a prison teacher), Spike Lee’s Clockers goes for broke almost immediately out of the gate with an opening credits montage of police photos of murdered African-American men. One is shown after another without apology. What is apparent after watching the film is that they can be considered casualties of circumstance and even fate.

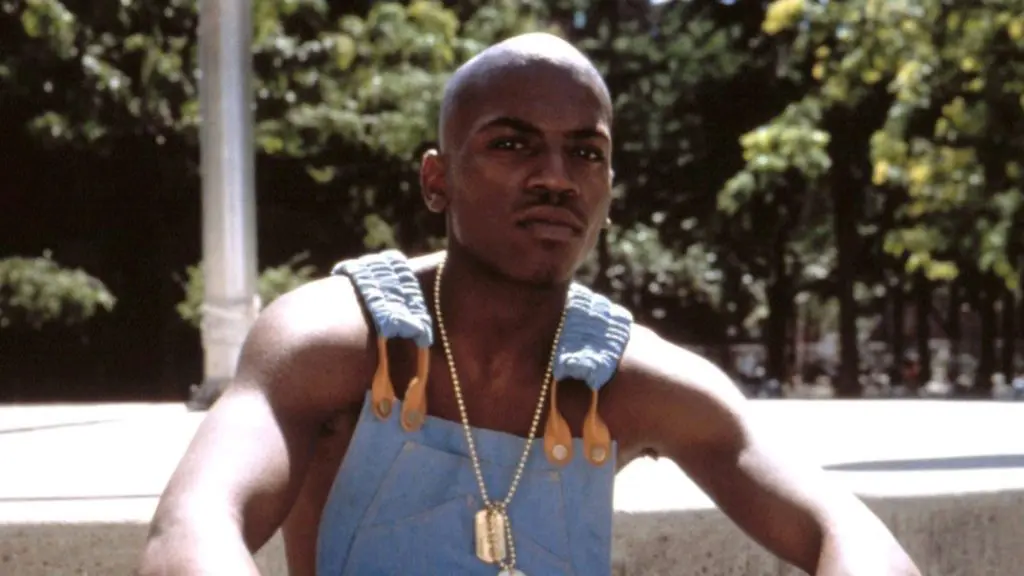

The film centres around a young man named Strike (at the time played by first-time actor Mekhi Phifer), who runs a crew in his project for a small-time kingpin named Rodney (the underappreciated Delroy Lindo), watched with disdain by the residents in the project that include a single mother (Regina King), a beat cop (David Keith), and an adolescent who wants to be just like him (Pee Wee Love).

The other storyline that brings it all together is when two homicide detectives investigate the murder of a young black man they think was killed for dealing out of the fast-food restaurant he manages. Detective Mazilli (John Turturro) doesn’t see the point of solving another dead drug peddler’s murder. Detective Klein (Harvey Keitel) has his eye on Strike – even though his brother, Victor (Isaiah Washington), confesses to the crime.

Brilliantly photographed by cinematographer Malik Sayeed (who also shot Spike Lee’s Original Kings of Comedy, Girl 6, and He Got Game), who uses light and shadows when scenes play out inside versus vibrant colours when shooting scenes outside, combined with filming onsite in the Gowanus Projects in Brooklyn, New York, give this joint a raw authenticity.

Two moments have lingered in my memory for a little over 20 years since watching the film. The first is a scene where a handful of white detectives (one being Keitel’s Detective Klein) are standing around the body of a young African-American male who was just murdered. The group cracks jokes, makes light of the loss of life with disrespectful (even jovial) racially-laced tones.

There could be two ways to look at this scene: one is that this is a way of dealing with the day in and day out emotional toll of “murder” police. The other is the lack of respect these white men have for the community members they serve, of whom the majority are black. Lee is gifted at: Showing you an image that commands your attention for all the wrong reasons.

It’s a blistering performance by Keitel, who leaves you wanting Klein punished for his deep-seated racism, yet feeling for him when the case leaves him a shell of himself. It ends with him being a changed man; we don’t know what way that will swing.

The other memorable moment is when Lindo’s Rodney schools his young protégé. He tells him, “If God kept anything better than cocaine, he kept that shit for himself.” It’s a stunning statement as he looks upon a woman waiting to buy from him and then cuts to a powerful musical score while watching the damage these men are causing. They aren’t the first to start dealing in these streets, but they are the current reason why this neighborhood is rotting from the inside while good people live there.

Lindo is electric in this role. With a snap of his finger, he can go from a lovable father-figure type to a dangerous sociopath who will do anything to make sure he won’t be the one going to prison.

Strike is caught between the will of both these men. He (the film never states his age, but you get the feeling he probably should still be in school) is playing the game to survive and desperately wants out. For much of the film, you are watching him calmly make chess moves, trying to stay out of prison or not become a victim like the ones we watched roll on the opening credits.

When Clockers was released almost 23 years ago, people criticized it for wrapping up storylines with a little red bow, and some characters had happy endings (bleak as those outcomes were). What wasn’t realized at the time is how revolutionary that really was. African-Americans in fictional entertainment don’t have to be killed off at the end of a film to wrap up a storyline. They do not have to be relegated to stereotypes, sent to prison, or product of their circumstance in film or television. These minority characters are fully realized and three-dimensional. In fact, it is a white homicide detective who finds out some startling revelations about himself and is now stuck in a world that doesn’t make sense to him. He isn’t the white knight, or the hero portrayed in films, that walks away clean. His life is left altered.

Clockers was years ahead of its time. It’s a visceral crime film that gives us a powerful look at the urban drug trade and the bleak despair of escaping your circumstances while exploring race relations between the police and the community they serve. It’s the “lost” Spike Lee Classic that was ahead of its time.