Summary

A simple story about a senior judge’s decision against the backdrop of her grinding-to-a-halt marriage made more complex because of the consequences. A film which will make you think about your world, instead of escape from it.

Damn, it’s not easy to write about The Children Act: the themes and subtle complexities deserve to be highlighted, but I risk telling you the whole story if I misjudge my words. Bear with me.

The scenario is this: a high court judge (Justice Fiona Maye, played by Emma Thompson) has got where she is because she puts everything into her work, where she is evidently very well respected. The main case of the film is one in which a boy with leukaemia needs a blood transfusion, but both he (nearly eighteen) and his parents are refusing. At the same time, the judge’s marriage to an American professor (Jack Maye, played by Stanley Tucci) reaches a crisis point. Her responses to both prove to be pivotal; particularly with regard to the former.

The Children Act was scripted by Ian McEwan, and based on his own novel. I confess that made me a little nervous when I first decided to go: Atonement was a great big punch to my spirit from start to finish, as I could just feel the doom growing; and Enduring Love was relentlessly painful too (though much more palatable). The Children Act does have a similar theme to Enduring Love, but much more thoughtful and mature; a more even blend of intellect and heart.

The director of The Children Act is Richard Eyre, notable for Notes on a Scandal, another successful novel adaptation. He applies here the same studied attention to characters and follows the natural pacing of the plot. However, I do think he makes it a little too sentimental in places, especially towards the end: my score would have been higher if his treatment had been gentler and less melodramatic around the denouement. But thing is, regardless of how much I liked that treatment, it worked: I cried heaps (and yes, thought about my life), in the middle of the film, and at the end.

You may have heard how marvellous Thompson is in The Children Act: “Oscar-worthy”, I’ve read, and “national treasure”. Don’t know if her reputation makes her a kind of Meryl Streep equivalent, but we’ve known this for some time. The role really suits her though: her legal cases are ones which blend family morality with medical logic, and Thompson adds some terrific humanity to what could be dry textbook stuff. She rarely tells us explicitly how she feels about what’s going on around her, or the decisions she has to take (and rapidly), but the strain is visible in every look.

A bigger surprise was the quality of the supporting cast. Stanley Tucci played the best role I’ve seen: I remember his love-to-hate role in Murder One, and he has grown his craft with his age. Tucci’s Jack was the perfect spouse to Thompson’s Fiona: we could see how sparkly the marriage used to be, no matter how flat it had become in recent months. We could see too just how strong his frustration and affection are towards his wife, with the slightest lift of his eyebrow. It’s interesting to see, as the film progresses, that the depth of Tucci’s acting skill is utilised to express unexpected shallowness of his character.

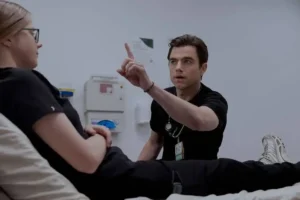

Fionn Whitehead was a revelation to me, perhaps not to those of you who saw Dunkirk. He plays Adam Henry ( “child A” in legal terms), the boy with leukaemia… I say “boy”, but he’s just a few months away from his eighteenth birthday, which causes an apparent legal grey area. He and his parents are devout Jehovah’s Witnesses; and honestly, I have never heard the rationale for denying a blood transfusion expressed so articulately, first by Adam’s father (Ben Chaplin, in a remarkable though brief performance), and then by Adam himself. Adam was very intelligent and creative, though within the boundaries of a sheltered and religious upbringing; Whitehead was impressive particularly in portraying the delayed teenagerhood that this young man went through as a result.

The cinematography (and direction of it) in The Children’s Act was successful in the way it focused on the human aspects of every set and took time in doing so. For example, we watched Justice Maye at home in her office, before entering the – comparatively sparse – courtroom when called; we also observed the care taken in looking after her gowns and travelling cases, such things that rarely get much attention in a more traditional courtroom drama.

And no, I’ve not mentioned the themes of The Children’s Act still: I’d rather you found out along with the main protagonist. Suffice it to say there is a good deal to discover – as always with McEwan – about the range of human emotions, and especially how some can go unnoticed, or cause confusion in their expression. The details of the film are to be found in those emotional nuances, rather than in the plot, which may not fit well for everyone. It is a beautifully written film though, despite some flaws; and I really hope the three main actors I’ve discussed above gain further recognition as a result.