Summary

The Last Black Man in San Francisco is a visionary film that’s an absolute stunner.

There are moments in Joe Talbot’s visionary film that left me with the feeling of being positively giddy from a satisfying fulfillment and then heartrendingly broken the next. Talbot’s personally emotive takes on tradition, love, family, loyalty, friendship, community, gentrification, and finding your place is an epic achievement of the soul. All of this is woven into our future, our past, and our present while remaining uplifting. The Last Black Man in San Francisco answers the call for those craving something different, genuine, more authentic than the franchise fare, remakes, or reboots of the world. They don’t make them like this anymore.

The story revolves around a man named Jimmie (played by newcomer and writer Jimmie Fails) and his best friend Monty (White Boy Rick‘s Jonathan Majors). The film follows two young men who I would guess are in their late ’20s and early ’30s, who run around the streets of San Francisco like kids who haven’t had a care in the world. The story is set in the not so the distant future, where the water and air are toxic (fish now have two sets of eyes), but it seems only white people are given masks and suits to deal with the pollution. Jimmie is an aide at an old folks’ home, treating his patients (and anyone he meets) with respect. Monty works in the fish market, hammering catfish over the head before selling them to customers while working on his playwriting.

The McGuffin that keeps the story moving is that Jimmie keeps visiting the house his grandfather built, a 1946 Brownstone that has been taken over by the gentrification of the residents of their old neighborhood. He comments about how the new residents don’t take care of the home, so he takes it upon himself to weed the garden, makes sure Monty knows the handrails are pewter and gives the windowsills a fresh coat of red when the owners aren’t home — well, that’s until they find him there again and hit him over the head with a couple of tomatoes to vacate the premises. Eventually, the house becomes available, and Jimmie begins a plan to reclaim the family property to reset the roots he once called home.

The film writing credits include the story by Talbot and Fails, with the official screenplay going to director Talbot and Rob Richert. It takes themes of racial, economic disparity, gentrification, and community in a strikingly original way, with rich dialogue and marvelous lyrical cinematography that enhances scenes that evoke a deeper meaning. Richert’s script isn’t interested in being a cut-rate heist thriller to obtain the once crown family jewel as it explores why Jimmie can’t let go of the past and step into the future.

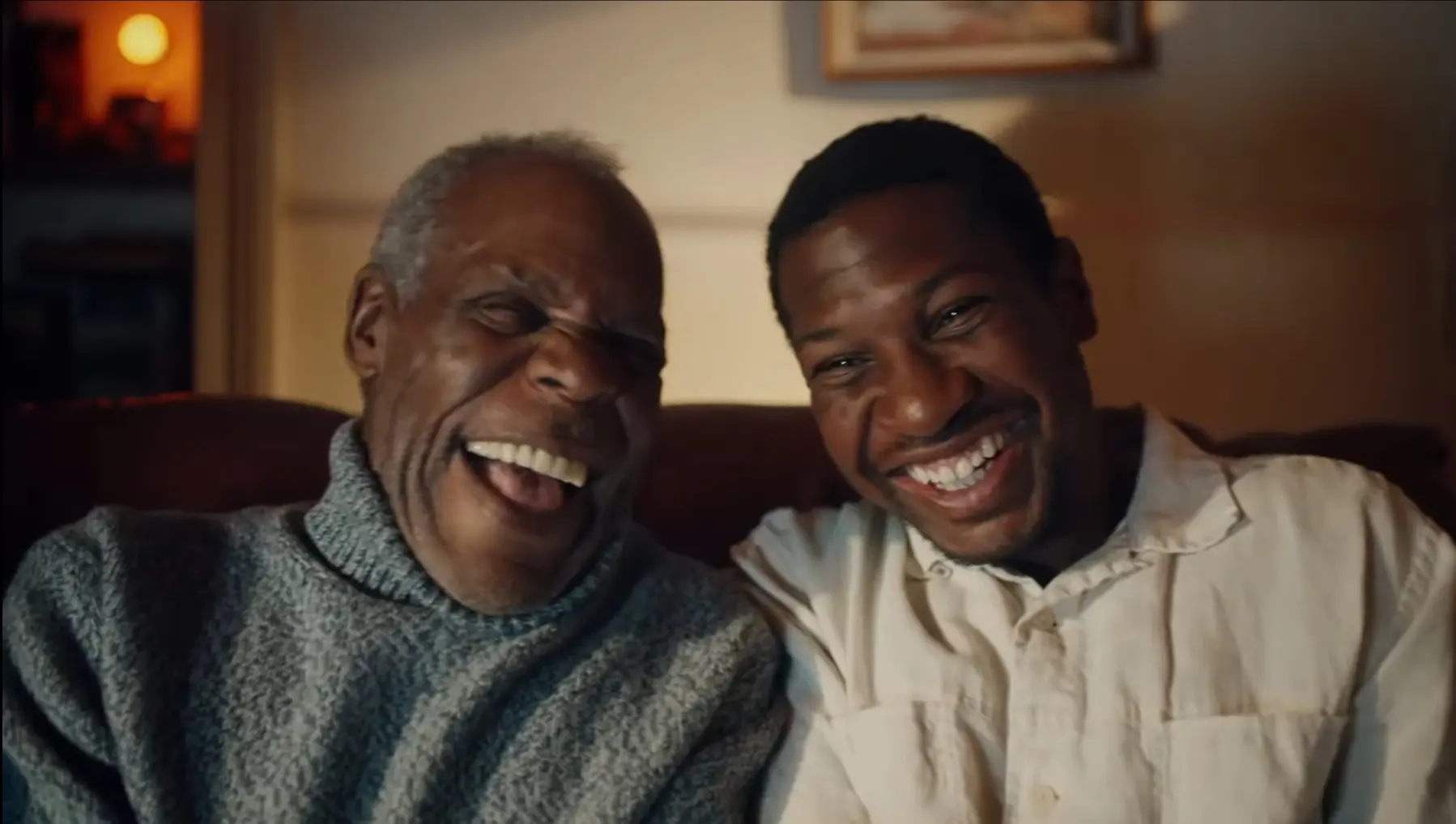

What makes The Last Black Man in San Francisco so authentic, absorbing, and satisfying is how it explores family, love, and traditions that have fallen by the wayside. In one beautifully shot scene, Jimmie explains to a tour guide the time, effort, and craftsmanship it took his grandfather to build the brownstone that was inspired by his service overseas in World War II. In another that I am certain will stick with me for some time, Monty is lovingly sitting next to his blind grandfather (the invaluable Danny Glover), arms locked in a loving grandfather-grandchild embrace as adults explaining to him what is happening on the program they are watching together, while smiles never leave their faces.

The film has some stellar turns from its supporting cast, including the wonderful Danny Glover and a scene-stealing Everyone Hates Chris’s, Tichina Arnold. The credit should go to the leads, where Jimmie Fails has most of the screen time and takes a stoic role that embodies the basics of any performer’s work: acting is listening. Fails invokes his innate ability to communicate his thoughtful glances that tell you everything you need to know without the tedious, repetitive dialogue while allowing Emile Mosseri’s exquisite musical score to enhance his scenes. When his character speaks, you need to listen because he’ll be delivering a line so perfect I wouldn’t spoil them here shortly.

Then there is the lightning in the bottle performance of Jonathan Majors as Monty. His character is a student of the human condition. A master mimic who needs to understand human nature so he can not only finish his play but understand and live in the world that surrounds him. It’s a beautifully rendered performance of almost childlike innocence, of a man who keeps dreaming, whose actions practically burst with vibrant life. This will all lead to a powder keg scene towards the end of the film that made me think I had just witnessed a true moment of greatness that had sent my hair standing straight up off my forearms with goosebumps in tow.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco is a visionary film about love and loss, family and friends, community and tradition, that touches themes that are all around us, are universal in nature, that so many of us take for granted — even though many have never had the opportunity. This is a striking work of originality about the cost of the American dream and how far out of reach it all really is. It’s an absolute stunner and one of the year’s very best films.