Summary

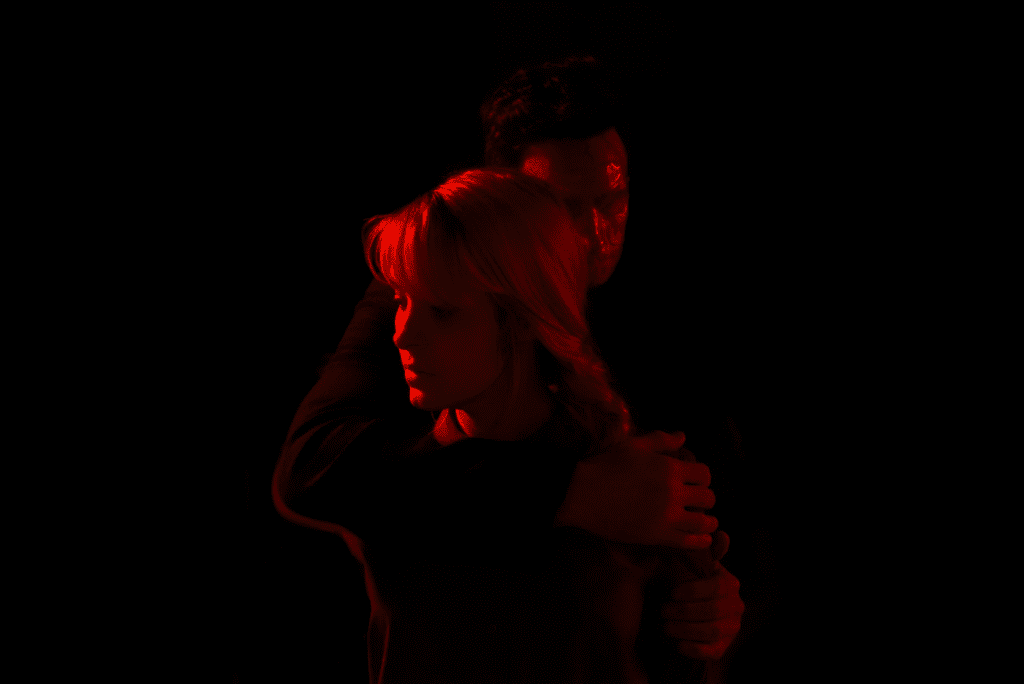

Observant and clever slasher/fable hybrid about unrelenting harassment and dismissal that women so often face. But is it horror? Oh yes.

Lucky is titled as such because of the myriad ways the word is used towards women who have been in what many would call unlucky situations. I’ve had it used towards me, and I’ve used it about myself: this film hit a few deeply personal nerves.

(And yes, Lucky is distinctly about women, and having lived as a woman for most of my life, it is very easy to understand the perspectives in the film. It’s no longer in my nature to talk in gender-binary terms, but that’s how the film presents, so bear with me.)

Lucky follows May (Brea Grant, After Midnight), who discovers a man breaking into the house one night. Her husband Ted (Dhruv Uday Singh) responds as though it’s hardly news: he comes every night to try to kill us; well, he mostly tries to kill her actually. They confront the stranger, he disappears, and – just as the husband has said – he returns to try again, night after night. May fights back, and gets a range of reactions from her peers, the police, and other authorities: disbelief, gaslighting, deflection; but mostly defeatist platitudes such as “that’s how things are.” Oh, and naturally, May is called “lucky” and “brave”.

In case it isn’t apparent, although Lucky looks like a light slasher flick, it is not strictly a narrative film but a surreal fable: this nightly intruder and the casual responses people offer to May are a metaphor for the intimidation and assaults women get daily in real life and the dismissal or disbelief they face. That’s a simple description: although not long, this film (written by Brea Grant, as well as starring her) does cover the scenario from many different angles. There are other women who have been through intimidation of their own, some accepting it as part of life, and some fighting back; there are those (particularly her husband) who suggest to May that she is overreacting, and authority figures who find it easier to assume she must be a victim of domestic abuse.

There is something especially insightful about the way in which dealing with the double whammy of an assailant and gaslighting every day is draining on May. She is spending all her physical energy, losing touch with her family, and almost ready to give in to the misogynistic ways of thinking by the end of the film. I don’t know whether Grant really considers this aspect of the modern world to be hopeless, but it feels that way at times: there is a strong sense that not only do women face these opponents and attitudes constantly, but also there is nothing to be done about it; the man will keep coming back, in one form or another, and there’s no way any of us can help everyone else.

Having said all that, Lucky is an extremely engaging film. Directed by Natasha Kermani (Imitation Girl), it is pacy, with no filler whatsoever, and – despite the familiar aspects – is full of surprises. The action, violence, and tension alike all escalate, or spiral, with horrible ease. Interestingly, although the intruder comes at night, what seems like well over half of the film is set in broad daylight, while May is going about her work, staying in touch with allies, and getting kitted up for the bad guy’s return. That sharp daylight puts the whole story in the real world, and yet May feels like she is entering another universe once the attacks start, because no-one seems able to accept what she tells them is happening. It quite makes her head spin when she discovers she’s not alone.

Jeremy Zuckerman’s music helped me to not take the film too seriously at times. It was plenty varied, starting out with simple string sounds and moving to voices and electronic tones later. The music was never overbearing or too intense, instead either lightening or complementing the mood.

It would have been easy to take it seriously. The man who assaulted me in my late twenties came into my home late at night to do so, and I recognized May’s experience when someone said to her, “I don’t know how you could stay in that house.” Like her, I had periods of not knowing whether I was to blame, or being punished for something; and like her, I struggled to find people who understood my experience. I could relate to everything in the film with one exception: I don’t think it was terribly realistic that a modern woman would be so ignorant of “how things are” until her thirties.

That’s the real horror.