Oppenheimer is about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Father of the Atomic Bomb. The film begins with Robert as a student facing criticism from a professor due to his struggles with the mathematics involved in chemistry at Harvard. After studying under Max Born, he obtained his Ph.D. in physics at the University of Göttingen in Germany at the age of 22. The film has raised many questions, especially with the ending when Oppenheimer has his final conversation with Albert Einstein.

As the film moved forward, Oppenheimer returned to the United States, where there was a lack of focus on quantum physics, and began teaching at the University of California, Berkeley. There, he meets his on-and-off-again lover, psychiatrist, and Communist sympathizer, Jean Tatlock, Nobel Prize laureate Ernest Lawrence, and his future wife, Kitty, with whom he has a child out of wedlock.

Oppenheimer Ending Explained

Lieutenant General Leslie Groves approaches Oppenheimer, wanting him to head the operation to build the atomic bomb. Due to his attendance at Communist Party gatherings, he initially faced disqualification from being part of Lawrence’s group. Despite his initial apprehension, Lawrence later explains that theory can only take one so far.

Robert decides to establish an entire town near his hometown in Los Alamos, New Mexico. This location is ideal, offering remoteness and a lack of any significant presence within a forty-mile radius, allowing for private discussions and focused work.

At the research laboratory site of the Manhattan Project, Robert and Groves recruit the world’s best scientists to join the project aimed at creating a weapon that can save humanity by letting the world know, if you have one, so do we.

Why does Jean Tatlock kill herself?

Ms. Tatlock ended her own life after Robert told her he could no longer see her again. That’s because he had to practice discretion, being the head of “Project Y” in Los Alamos. Initially, he broke up with her after cheating on her with Kitty, and she became pregnant. (Kitty was also married to another man at the time).

However, during the initial breakup, Robert tells her that he will always answer her call. Now, after sleeping with her while married to Kitty, he cuts off ties with her, most likely because of her ties to the communist party, which started in her days at Stanford with the Bay Area’s Communist Party community. Jean killed herself on January 5th, 1994, a day after Robert visited her for the last time.

Who was that traitor at Las Alamos?

While Groves suspected anyone with former ties to the Communist Party as possible traitors, particularly suspecting Rossi Lomanitz, Klaus Fuchs gathered intelligence for the Russians while working at the Manhattan Project. Klaus, a German theoretical physicist, immigrated to England after being told he was “no longer German” when the Nazis came into power.

Fuchs had previously worked under Max Born, which likely contributed to Oppenheimer’s welcoming him to the project without suspicion. However, this association cast a shadow of doubt over Robert, as many perceived him as a Communist sympathizer and potentially disloyal to America when his curiosity was purely intellectual.

Fuchs’s primary contact was a man named Harry Gold, to whom he transmitted information regarding the Atomic Bomb and the possible development of the Hydrogen Bomb.

Who was Lewis Strauss?

Strauss was the man behind the curtain in the attempt to assassinate Oppenheimer’s character. Initially hiring Oppenheimer to teach at Berkley, he served as the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. According to the American Heritage Foundation, Strauss wanted to study physics but could not afford the tuition, which may have caused animosity towards Oppenheimer, as seen at the film’s end.

Nolan’s manipulation of the timeline presents Strauss as a sympathetic character. Still, he ultimately used Oppenheimer as a pawn, preparing a cover for any potential negative consequences from his work on the Commission for political gain. As Oppenheimer grew vocal in his opposition to the development of the “H-bomb” later in life, Strauss devised a plan to have his security clearance revoked.

Why was Oppenheimer not given a jury trial?

Rather than a jury trial, a private hearing was arranged to accuse Robert of his alleged communist connections, leaving him with little opportunity for defense. Strauss went as far as to question his leadership at the Manhattan Project, even bringing up his philandering in front of Kitty at a hearing. He was labeled a threat to democracy and subsequently barred from further government work.

However, Eisenhower rejected Strauss’s nomination as Secretary of Commerce after scientist David Hill, portrayed by Rami Malek, testified in defense of Oppenheimer and condemned Strauss during the hearing.

What does Oppenheimer say at the end of the film?

At the end of the film, Oppenheimer says, “I believe we did,” while reminiscing with Albert Einstein about if the feared “chain reaction” of the atomic bomb would destroy the world. They worried that its detonation would have such intense heat that it could end all human life on Earth, turning the atmosphere into fire with a power akin to the sun.

Even though Earth remained and was not destroyed after the Trinity nuclear test and the bombing of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Robert believes they have done just that, perhaps because they opened Pandora’s box regarding escalation. As Nolan fans know, this is a common theme from the transition of the director’s Batman Begins to The Dark Knight.

This revelation brings us back to the quote he read to Jean in Sanskrit: “Now I become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” We can now draw parallels to J. Robert Oppenheimer as an “American Prometheus” (a reference to the source material the film is based on), the God of Fire, who in Greek religion is associated with fire and the creation of mere mortals.

Does Oppenheimer have a post-credit scene?

No, Christopher Nolan’s film has no post-credit scene, so feel free to sprint to the bathroom after the film’s three-hour running time.

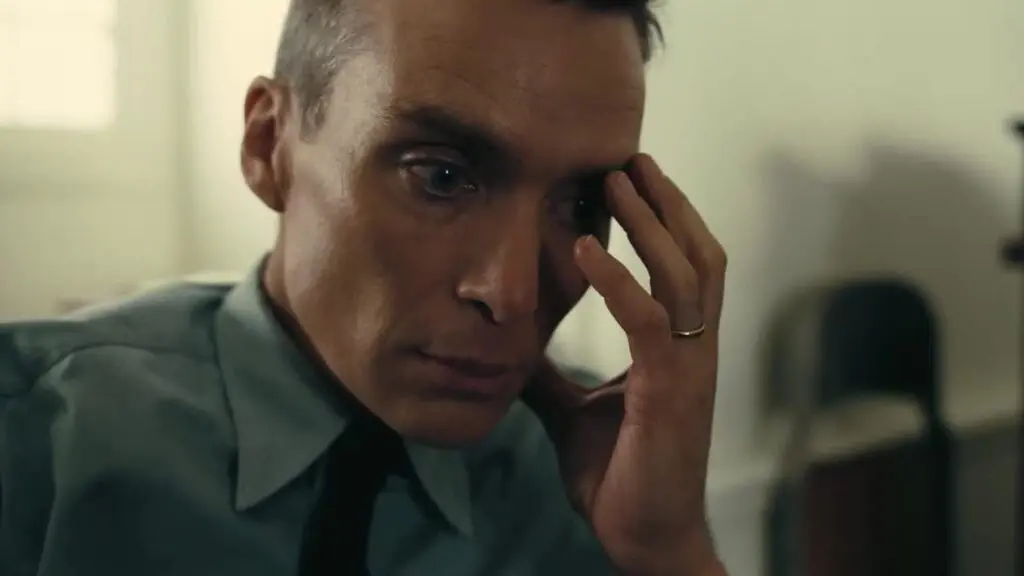

Cillian Murphy as Robert Oppenheimer in Oppenheimer (2023) – Image Courtesy of Universal Pictures

Oppenheimer Detailed Review

Very rarely does a studio picture surprise me anymore. Yet, after watching Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, I walked away from the movie speechless (well, practically, anyway). It’s almost impossible for me to stay wide awake and confidently witness such true greatness.

It’s as if everything Nolan has done is practice for this very moment. From Interstellar’s existential crisis and windstorm visuals to the classic themes and pulsating soundscape design across The Dark Knight Trilogy. From the technical prowess of Inception and the film’s exploration of the depravity of humanity and the subtle allure of the free will of Tenet.

And there are more. Like the subtle shades of distortion of memory in films like Dunkirk or Memento.

Even the latter’s exploration of personal identity. The close-up view of free will in Tenet, the allure of power in The Prestige, and the obsession of his first film Following. Of course, the classic Nolan is across his entire filmography of causality.

All of Nolan’s abilities are there and left for the audience to see. This leads me to my thoughts on Oppenheimer, which are to the point. It’s the greatest biographical film ever made. You won’t have a better cinematic experience, in total, all year or maybe in the next few.

Oppenheimer stars featured Nolan player Cillian Murphy, who is phenomenal here, as the titular subject. The film starts with the young Father of the Atomic Bomb in school, struggling with mathematics in the professor’s view.

After acquiring his Ph.D. in physics in Germany, Oppenheimer returned to the United States because no one was working on quantum physics.

Robert then starts to teach at the University of California at Berkeley (in reality, splitting his time with Caltech). Robert meets his on-and-off-again lover Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), 1939 Nobel Prize winner Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett), who knows theory will only get you so far, and his future wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt).

There, Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) approaches him, requesting Oppenheimer’s involvement in creating the atomic bomb, but only after Oppenheimer assures them he has no ties to the Communist Party.

From there, Robert recruits the world’s most outstanding scientists to save the world by creating the atomic bomb, despite the worry of worldwide escalation.

Based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, Oppenheimer is epic in scope, encompassing a period of fear and paranoia that led to a collective effort of hubris.

Except, what Nolan does here is set his biographical film against the backdrop of a race-against time-thriller.

The result is equally as nerve-racking and thrilling as it can be overwhelmingly powerful. Case in point, the first two acts lead to the testing scene, and the gravitas of the moment and visuals are awe-inspiring. Nolan examines what it’s like for Oppenheimer to be considered a hero. And, of course, sticking around long enough to be the villain and hero again.

Murphy delivers an astonishing turn that transcends standard biographical fare, capturing Oppenheimer’s obsession, drive, and brilliance throughout various stages of his life, with subtle timeline shifts reminiscent of Nolan’s trademarks. The actor fully embodies the man’s dedication, reportedly emulating Oppenheimer’s intense concentration by eating only a single almond daily.

Oppenheimer is brilliant and a masterpiece in biographical and technical filmmaking that never wastes a single moment.

For one, the film’s final words spoken by Murphy are Nolan’s kiss to the world, and the collective gathering of Los Alamos residents to celebrate their victory will go down as one of the most hypnotic in film history.

Oppenheimer is a perfect film. Nolan’s biographical work is worth watching for Hoyte van Hoytema’s stunning minimalist cinematography, Ludwig Göransson’s pulse-pounding sound design, and the many fine performances.

Expect Oscar nominations for Murphy, Damon, a scene-stealing third act from Emily Blunt, and Robert Downey Jr., who portrays politician Lewis Strauss, as well as a plethora of nominations for their outstanding achievement in sound design.