Summary

It might be the sequel nobody asked for, but Jurassic World has enough wit and imagination to offset the thin characters and sloppy plotting.

The other morning, I awoke to an email from a friend concerning his opinion on Jurassic World: “I’m glad they finally realized how fucking stupid all this is”.

I know what he means. Unlike him – who sometimes seems utterly devoted to tearing down the 1993 original – I’m personally of the opinion that Jurassic Park is about as perfect an adaptation as that story was ever going to get. But I understand. It’s a ludicrous idea, full of ludicrous characters and set-pieces. Where Jurassic World differs is in knowing this about itself. For the same reason that the otherwise okay Fast and Furious sequels have taken on a previously unimaginable level of quality and prominence, Jurassic World works as a charming, dumb-fun summer blockbuster far better than it really has any right to.

My friend was only at Jurassic World because his girlfriend wanted two hours of Chris Pratt, and in the interest of preserving an easy life, he agreed to go along. Outside of movies like this one, that’s how relationships work. I’d seen it the day before, at an evening showing with one of the more diverse crowds I’ve been a part of for a while. I wasn’t aware of anyone clamouring for another instalment of this franchise; maybe they didn’t know they wanted it until they got it. Either way, the place was packed. A few seats to my right, an older couple kept loudly vocalising their memories of the first three movies, two of which were directed by Steven Spielberg, the third by Joe Johnston. In front of me were a group of teenage girls who seemed as enamoured with Pratt as the movie does, and behind me a couple of brothers not unlike Ty Simpkins and Nick Robinson, who play the two siblings who’ve been shipped off to the prehistoric theme park so that their parents (Andy Buckley and an exasperated Judy Greer) can finalise their typically amicable divorce. Those two kids in the theatre wanted dinosaurs and dinosaurs only – I can’t imagine they left disappointed.

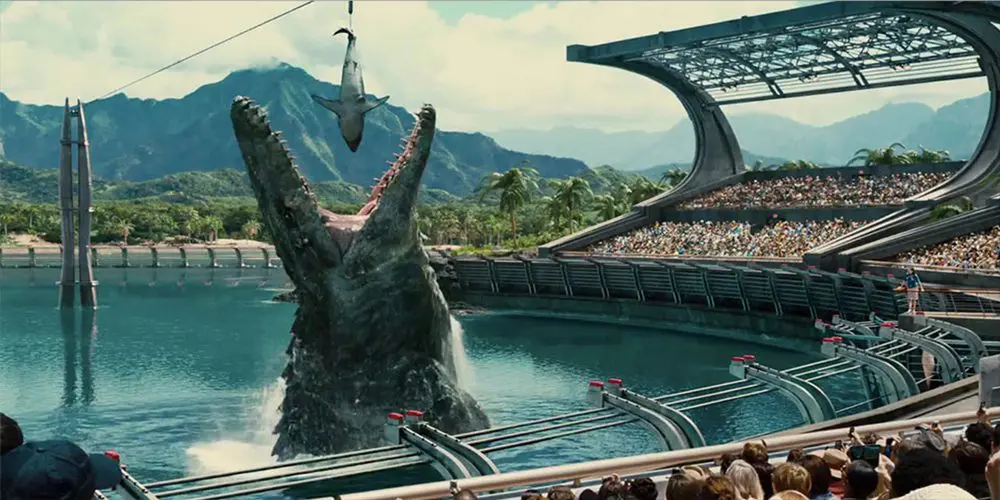

Jurassic World trades in a few big ideas, but the one most central to the plot is that of a gene-splicing big-business strategy that throws together science and capitalism in the same way that BD Wong’s returning geneticist has thrown together the DNA of T. rex and who knows what else. Public enthusiasm for the eponymous island attraction has dwindled over the decade since it’s opening, and so upper-management has genetically-engineered something new to keep the blasé attendees on their toes. It’s called Indominus rex; it’s big, it’s ugly, and it’s smart enough to stage an elaborate escape from captivity.

It’s also, it must be said, utterly absurd, possessed of abilities that wouldn’t have any value or function in a zoo attraction (among them camouflage and self-regulated body temperature). This is partially explained: the science and business teams worked on Indominus with InGen private security contractors, and its full genetic provenance is classified because it would likely reveal all the silly ways it was supposed to function as a military weapon. I’d probably be okay with that if it didn’t feel like a subplot transplanted from a completely different movie. There are characters (like Vincent D’Onofrio’s no-nonsense paramilitary bruiser) that seemingly exist for no reason other than to openly scheme about this, but it goes nowhere and adds nothing besides a single dangling thread for sequels to yank on and unravel.

Of more immediate concern is the fate of Gray (Simpkins) and Zach (Robinson), the two quintessential Spielbergian brothers stuck in the middle of Indominus’s killing spree. Gray is the younger, nerdier of the two, and knows more about previously-extinct animal species than seems reasonable. Zach is too hormonal to care about any of that and is instead using his time at the park to stare lustfully at any female who wanders into his general vicinity. (Gray has a funny line about this which is a damn-near perfect awkward little-bro moment). The movie is produced by Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, and these two could have been body-snatched from anywhere in its catalogue. A lot of what director Colin Trevorrow and the three other credited writers have done with Jurassic World feels deferential to Spielberg, who has always been one of the most talented filmmakers to build an adventure atop familial schmaltz without being irritating or manipulative. Zach and Gray tread a fine line between saccharine and sweet on occasion (this isn’t, after all, actually a Spielberg picture) but for the most part they tend towards the latter – particularly Simpkins, who’s a dead-ringer in both appearance and wide-eyed, bright-faced manner to Sean Astin, who played a similar character in The Goonies.

Sometimes the nods and winks are aimed broadly at Amblin’s whole body of work and others at the first three Jurassic movies specifically. Jake Johnson, for example, plays one of the park’s technicians; he wears t-shirts emblazoned with the original Jurassic Park logo, keeps dinosaur figurines on his desk, and abhors what Irrfan Khan’s flamboyant billionaire has done with the resort. That’s about as subtle as things get. Elsewhere, the movie’s hero, Owen Grady (Pratt), is doing as faithful an impersonation of Indiana Jones as you possibly can sans bullwhip, and his frosty love interest, Claire Dearing (Bryce Dallas Howard), works with and against him in much the same way Marion did with Indy.

All this should feel unseemly, but the movie genuinely loves Grady and the cast seem to feel the same way about Pratt. At one point, as he barrels through the park’s wilderness on his motorcycle flanked by a pack of velociraptors, Zach, who is watching this on a live feed, says to Claire, “Your boyfriend is a badass”. He doesn’t seem to be acting. Claire runs the park and is the boys’ estranged, careerist aunt, but she’s paper-thin and the writing doesn’t offer her any more dimensions. The focus is on Grady, and on adding one layer of implausibility after another. He’s ex-Navy. He’s an animal lover. He’s a man of science. He’s managed to sort-of tame a pack of raptors, and he’s vehemently against what’s being done to the dinosaurs in the name of profit. As far as I can tell there isn’t even a field of study against which to prop all these ludicrous talents – he can just do everything, and do it better than everyone else, solely because he’s the hero. Jurassic World’s attitude to good-guy heroism and masculinity is as prehistoric as the park’s residents, but never in a way that feels mean-spirited. It’s as much as part of the movie’s carefree, tongue-in-cheek energy as everything else. Pratt has the air of someone who spent a significant portion of their life being fatter and less attractive than they are now. His allure has a self-conscious streak to it. At 35, his appeal is that even when he’s playing a character as ridiculous as this one, he still seems like a real person.

Trevorrow’s only other movie is a time-bending genre-comedy called Safety Not Guaranteed. I haven’t seen it, but I know people liked it. The comedic background’s hardly a surprise to me; a lot of Jurassic World is played for laughs, and not just the lines delivered with a wink and a smile. The movie’s bravura set-piece – a shrieking, zooming sequence in which the park’s pterodactyls flee their aviary and aerially molest the languishing patrons – is very funny, and not in a way that feels unintentional. The winged dinos swoop down and scoop up fleeing human beings in the same way a seagull might snatch a hotdog. One guy runs for his life with a beer in each hand, which is easy to relate to if you’ve ever bought a pint at a pricey theme park – I probably wouldn’t leave them either. This whole scene wouldn’t work half as well had it been going for shock, and likewise, the whole movie has a playful quality that takes the pressure off both it and Trevorrow’s handling of it. In one sense it’s disappointing when a promising director gets sucked out of the independent scene and offered the caretaking duties of an old, well-respected franchise like this one. In another sense, these are the guys who bleed their influences in sloshing, frothy torrents. Those pterodactyls, in more ways than one, are directly related to The Birds. But Trevorrow seemingly knows how to remould iconic scenes in a way that feels his. The movie’s littered with them. He might be decorating a new house with old furniture, but he has his own sense of feng shui.

I couldn’t honestly say quite how well Jurassic World works solely on its own terms, but I never got the sense it was supposed to. You don’t necessarily have to get all the references to enjoy this movie – that’s part of its shrewd charm. There’s wit and imagination, and the three or four big action sequences are worth the price of admission alone. But it’s a movie that takes a lot of pleasure in playing on and subverting your expectations. One of those action scenes is the most wonderfully absurd bit of fan-service I’ve seen in a blockbuster, and you can feel the movie bending over backwards to accommodate it. Unlike its hybrid super-predator, Jurassic World seems completely aware of its genetic makeup; its heritage, its strengths and weaknesses – the parts of it people are paying to see. The worst aspects are legitimately bad: thin characterisation, sloppy plotting, and a sneering attitude. The best, though? That stuff’s good enough to make sure you don’t care.