Summary

Arrival is stunningly-made science-fiction that, by the end, manages to slightly undermine its own themes and ideas.

Arrival is a movie about humanity’s first contact with an unknowable alien race, which is funny because sometimes I feel like I’m the only person in the universe who has any sense. You’ll understand why soon in my spoiler-filled review.

See, everyone loves Arrival. Critics love it. Audiences love it. You, dear reader, probably love it too. Me? I do not love Arrival. I actually dislike it quite intensely, for reasons that are varied and numerous and difficult to explain.

Difficult, because it always is talking about a movie like this; about anything, really, that most people seem to enjoy. But especially difficult in this case, as Arrival is built around a significant plot twist, and, when it eventually reveals itself, how you felt about it will likely determine how you felt about the movie overall.

We’re all adults here, so I’m going to talk openly about that twist and various other leaky holes in Arrival’s plot, any one of which the audience could fall down and break their legs at the bottom of. If that bothers you, don’t read on. Or, better yet, go out and watch the movie, then come back when you’re done. Okay? Okay.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein famously stated that if a lion could speak, we wouldn’t be able to understand him. The point he was making, I think, is that the experiential differences between a human being and an animal are so incomprehensibly vast that even if we shared a language, we’d have nothing worth saying to each other.

You’d think the same would apply to alien squid monsters, but Arrival calls bullshit on this idea. Its heroine, Dr Louise Banks (Amy Adams), is a professor of comparative linguistics who was once seconded as a military advisor to translate a video of Farsi-speaking insurgents.

When a dozen giant spacecraft materialize and drop anchor across the globe, one of them in the Montana wilderness, who else are you going to call? Colonel Weber (Forest Whitaker) shows up on Louise’s doorstep. He wants her to ask the aliens what they’re up to.

She’s uniquely qualified to do this, which you can tell, because, at one point, she writes her name on a whiteboard in English and reads it aloud to the aliens while pointing at herself.

Louise’s partner in this endeavor is Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner), a physicist who spends the entire movie not doing any physics and instead genially mimicking all of Louise’s advanced linguistic techniques. (He also writes his name on a whiteboard.)

Her enemies are not the aliens themselves, but instead the world’s various hair-trigger governments, particularly those of Russia and China, naturally, who are all in a rush to doom us with a full-scale military response. So, to be clear, Arrival posits a scenario in which humanity’s only hope for survival is two morally-upstanding intellectuals learning to peacefully communicate with the visitors. It’s science-fiction not as bug-zapping space fantasy but as a hopelessly idealistic parable; a story that leans heavily into thinking at the expense of feeling.

This is not, in itself, a bad thing. Humans have been fucking up extra-terrestrials for as long as the genre has existed, and it is about time they sat down and had a chat. Even among its recent contemporaries Arrival is solid enough entertainment; it’s certainly better than Christopher Nolan’s preposterous Interstellar, if for no other reason than it has too much self-respect to bury it’s final third in hippie mumbo-jumbo.

The parts of it that work do so in more or less the same way as Ridley Scott’s The Martian, but it lacks that movie’s sense of humour and global cooperation, and it doesn’t have the same confidence in the intelligence and likeability of its characters. Louise and Ian are only smart because of their constant proximity to dummies; only worth rooting for because nobody else is being reasonable.

The dudes with guns are moronic and dangerous purely by virtue of being dudes with guns, not because of any explicit flaw in their thinking. In fact, there’s a case to be made for a militarized response being slightly more appropriate than a relaxed meet-and-greet, especially in light of how the aliens suddenly reveal themselves, but Arrival isn’t interested in making it.

The movie’s screenplay, which was adapted and expanded by Eric Heisserer from a short story by Ted Chiang, clearly has aspirations of intellectualism, but this kind of lazy shorthand consistently undermines it.

You can almost guess a character’s moral alignment by how they’re dressed: uniforms and shirtsleeves denote idiocy and evilness; shabby casualwear symbolizes intelligence and rectitude. This is atypical science-fiction that, ironically, only knows how to communicate in a language we already understand.

The director here is Denis Villeneuve, working for the first time with Selma’s cinematographer, Bradford Young, and he lends Arrival the same stately pace as his other recent films (Prisoners, which I liked, and Sicario, which I loved). He’s well-suited to this material. The big visual reveals are sober and deliberate but immediately evocative, even when they shouldn’t be.

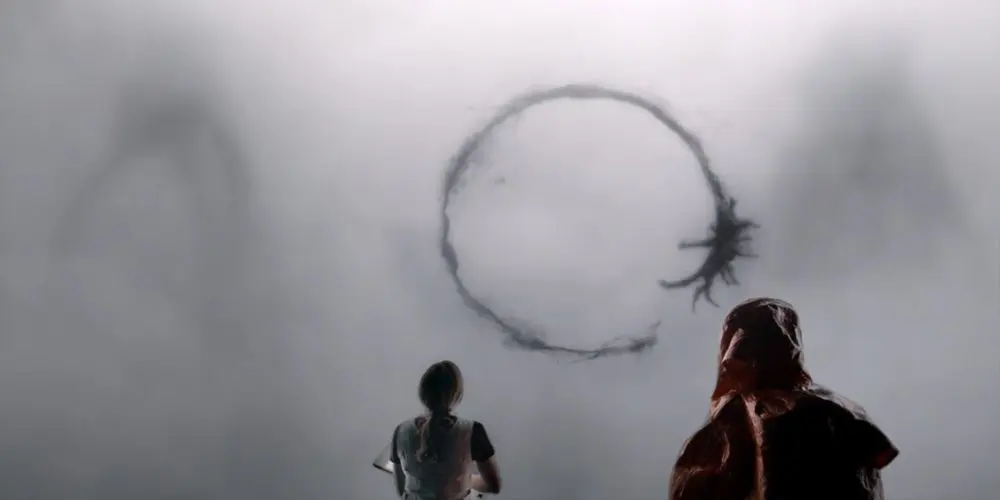

The colossal obsidian-black starships look like pebbles; skipping stones stand upright. They’re ridiculous. But Villeneuve treats their emerging from the mist as though it’s momentous and mysterious, and it becomes so. The ships have little square shafts in their base.

Through these enter Louise and Ian, flanked by military personnel and technicians. Inside, they become weightless, untroubled by gravity, and the entire structure rotates 90 degrees, such that the shaft becomes a corridor, one of its walls the floor, and at its end float two squid-like lifeforms on the other side of a transparent barrier.

This is a tremendous sequence. It’s everything Arrival could and should have been. The low, menacing horns of Johann Johannsson’s score boom all the while.

What’s wrong with the Ending of Arrival?

Louise and Ian call the aliens “heptapods”. Seven tentacles. Makes sense. They also call the two behind the barrier “Abbott” and “Costello,” which would be okay were it not for a scene later in the movie, when Louise meets Abbott and asks it directly about Costello’s whereabouts, and the fucking thing gives a direct answer.

It speaks. Not in English, but Louise understands it well enough, and the movie helpfully provides subtitles for the audience. Then Abbott explains the plot twist to Louise. And suddenly, I’m lost. Isn’t the whole premise of this movie predicated entirely on human beings not being able to communicate with these creatures? Why is it that this otherwise unremarkable linguist is the one person on Earth who can have a conversation with them? And why so suddenly, after spending the entire movie up to that point, painstakingly deciphering their bizarre writing?

The answer to all of these questions is this: Because the plot needs her to. This is why the twist didn’t work for me. It’s deployed to show off its own cleverness and how carefully it was woven into the narrative, but it requires that the movie breaks its own established rules in order to make the reveal work.

What is the reveal, you ask? Well, as it happens, it’s some seriously high-concept, thought-provoking stuff. The heptapods see time as non-linear; they can look into the future the same way human beings can remember the past. They’re here on earth to telepathically gift us with the same ability – an ability that Louise has somehow already inherited, which is why she has nightmares about the death of a child she hasn’t given birth to yet and how she can solve our current problem by asking future-Louise what to do.

To Arrival’s credit, this works on a mechanical level better than it has any real right to. But it doesn’t work thematically. It doesn’t support any of the movie’s previous ruminations on cold intellectualism versus rash emotionalism. It exists to be smug about itself.

And, I suppose, it exists to provide some semblance of a happy ending. Of course, Ian is the daddy of future-Louise’s future-baby. How romantic. And, of course, Louise decides to have that baby anyway, condemning her child to a long, painful death at a young age because she will treasure every moment before that. How ro-… hang on. Isn’t this supposed to be a happy ending? That’s the most selfish shit I’ve ever heard.

RELATED: