There’s a moment in Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation (the fifth of these movies – they don’t always put numbers on them) in which Tom Cruise’s extra-special agent, Ethan Hunt, knifes his way into a centrifuge chamber full of water and swims against the current with no scuba gear to rewire a security system. The whole time you can hear his heartbeat, the way you can hear your own whenever you’re underwater. That was the moment I realised what it is that makes Cruise the very best action star on the planet: that heart beats for us, the moviegoers. Not in the sense that he needs us to buy tickets, either; he doesn’t anymore. The guy’s been one of the biggest stars on the planet for longer than I’ve been alive. And, at 53, he certainly doesn’t need to keep putting his own body on the line in these distressingly-realistic stunt sequences. He’s already proved his point, and never better than in the last of these movies, 2011’s Ghost Protocol, which featured the only action set-piece in anything I’ve seen that made my palms sweat in legitimate fucking dread. What is it, then, that compels Cruise to repeatedly appear to risk his life onscreen? It has to be us. If he’d have drowned in that chamber (and he almost does), his heartbeat wouldn’t have ceased. The relentless enthusiasm of Cruise is too powerful. At this point, he’d continue making these movies if all that was left of him was his steadily-beating heart, sitting on the arm of a director’s chair.

This time around the director is Christopher McQuarrie, whose last movie, the abominable Jack Reacher, also starred Cruise. The novel on which it was based, Lee Child’s One Shot, is a twisty whodunit about a lone gunman opening fire on a plaza-load of civilians in a small Indiana city. It’s a decent book, one deserving of a better adaptation, but it was the wrong material for Cruise – both as an actor (he’s a foot shorter and a hundred pounds lighter than the book’s protagonist) and as a star. Cruise works best without boundaries – narrative, national, budgetary. He’s at his peak in a loopy plot which allows him to stamp his passport as many times as possible, while running, jumping, fighting, shooting, swimming and smirking his way through joyously ludicrous action sequences and legions of heavily-armed, less-cool bad guys. Rogue Nation, then, is just about the Cruise-iest Cruise movie in the history of Cruise.

And that’s saying something – particularly with this franchise, in which he’s always been an essential thread holding together a surprisingly distinct string of movies. Brian De Palma’s 1996 original is tonally and stylistically unlike anything that would follow it; it’s most iconic sequence, in which Ethan Hunt, suspended from wires, breaks into the CIA’s Langley headquarters, feels almost anti-Cruise at this point. But Mission: Impossible also introduced the touchstones that each subsequent instalment would call back to: the Impossible Missions Force (the IMF), and the team that Ethan would either assemble or have assembled for him; the self-destructing assignment tapes; the secure location which contains a MacGuffin that must be stolen; and Ethan himself, the charismatic super-spy who is never above suspicion but always one step ahead of his peers, his opponents and the audience. The directors have changed for the sequels (John Woo, J.J. Abrams and Brad Bird, respectively, did the next three), and between each the series has quietly performed a soft-reset, wiping the slate clean for each new creative team. The movies never lost their priorities, interests or sense of self, but by Ghost Protocol it was understood that major plot points and minor characters would be excised to make room for new ones.

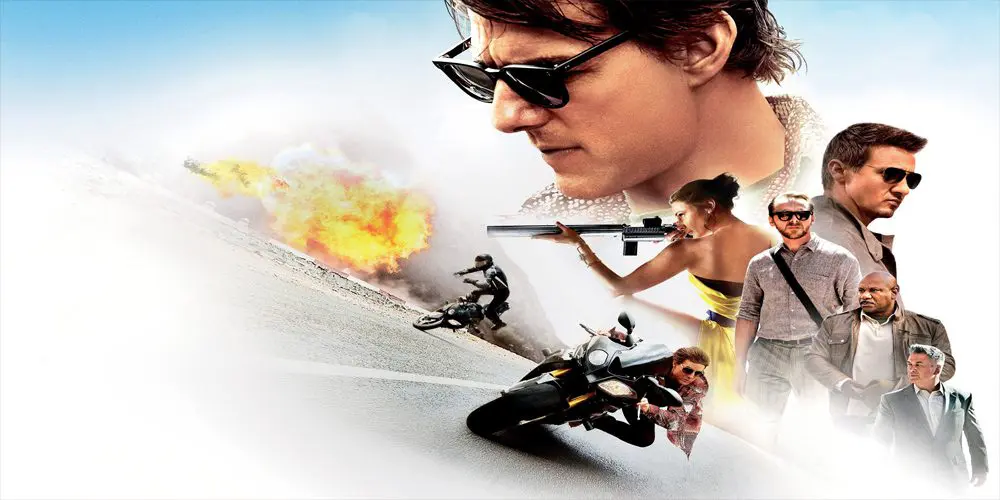

Rogue Nation immediately veers off the established path, referencing events from the previous movie and lassoing recognisable characters into this one. William Brandt (Jeremy Renner), for example, another IMF agent, wants to stop a government oversight committee from dismantling his organization and handing it’s workload over to the CIA, which Alec Baldwin runs with formidable hauteur (his character has a name, Alan Hunley, but he’s basically just Alec Baldwin). Washington thinks the IMF are impulsive mavericks with a “disregard for protocol”, and that their “unorthodox methods are indistinguishable from chance”. They have a point, so the IMF is disbanded and absorbed, rendering the missing Ethan Hunt a fugitive who Hunley is obsessively eager to hunt down.

Ethan’s missing because he’s on the trail of the Syndicate – an international criminal consortium comprised of presumed-dead covert agents and led by a disgraced Brit, Solomon Lane (Sean Harris), who wants to affect global change by bringing down passenger planes, assassinating heads of state and blowing things up. Honestly, it’s never really made clear exactly how any of this wanton destruction is supposed to help Lane achieve what is already a rather unspecific goal, but whatever – this, like the bare-bones caper plot of the last one, is less an actual narrative we’re supposed to follow and care about than an all-expenses-paid scenic tour of various real-world locations and landmarks that Tom Cruise and his friends race through and demolish.

Along with Renner, Rogue Nation also brings back Simon Pegg’s lovable tech wiz, Benji, and Ving Rhames’s ex-agent Luther, who is the only figure other than Cruise connecting the whole franchise together. A lot of this movie’s wit comes from Pegg, who was good in Ghost Protocol and is even better here. His exasperated lightness is the perfect antidote to whatever it is Cruise is playing with Ethan, who at this point is not so much a character as an omnipotent avatar through which McQuarrie is celebrating the idea of Tom Cruise rather than Cruise himself.

New to this edition is Rebecca Ferguson as an agent, Ilsa Faust, deep undercover in the Syndicate’s inner-circle. Another calling card of the Mission: Impossible franchise is a woman who falls in love with Ethan; Faust is that, to a degree, but also a great deal more, and Ferguson’s mixture of tender and tough keeps her loyalties to him, the Syndicate, her country and herself in a constant state of flux. If it hadn’t been for Mad Max: Fury Road and Imperator Furiosa earlier in the year, Ilsa would have been the action heroine of 2015’s summer; beautiful, competent, compelling, and really only lacking the long-term cosplay appeal of Charlize Theron’s bionic badass. I’d never seen Ferguson before, so she was my biggest and most welcome surprise of Rogue Nation.

The action sequences were less surprising in that they are, without exception, phenomenal examples of storytelling and cinematography – each is predicated on an understanding of reality and physical space, each has a clear beginning, middle and end, each reveals more about the characters and their relationships to one another, and they never hit the same note twice. The most talked about is that opening sequence, in which Cruise affixes himself to a plane as it’s taking off with a bellyful of nerve gas. The funniest is a bout of drunk-ish driving through the streets and market stalls of Morocco; the most compelling a silent fist-fight in the rafters of Vienna’s State Opera House, as Cruise battles a Syndicate goon atop swaying trusses. Some of these passages reach Raiders of the Lost Ark-levels of escalating complication, but every single one is shot with clarity and played for maximum thrills. The director of photography, Robert Elswit, who did Ghost Protocol and the tremendous Nightcrawler, is one of the very best cinematographers in the business, and his presence lends a long-awaited visual consistency to the Mission: Impossible franchise that the first three movies lacked. You’d be hard-pressed to find three more different filmmakers than De Palma, Woo and Abrams, and consequently their contributions felt like director’s movies in a way that the latter two don’t. Rogue Nation in particular seems to see Mission: Impossible less as an overarching narrative than a rubric for a certain kind of self-satisfied action moviemaking, a glittering monument to muscles and mayhem. And at the centre of that, as always, is Cruise.

The key to Rogue Nation’s appeal isn’t Ethan Hunt as a conception, but as a conduit. Through him, Cruise can really cling to the doors of ascendant aircraft, can really hold his breath for minutes at a time, can really plug himself into the screenwriter’s brain and tickle the audience’s nerves. His overwhelming need to be a walking, talking special effect fuels our own need to witness him defying expectations and terrorizing studio insurance companies. In each of these movies is a mandatory scene in which one character peels off a fleshy face-mask to reveal another underneath. We always feign surprise when it happens, like we really weren’t expecting it. But there aren’t any surprises in action cinema anymore, not real ones. With Rogue Nation McQuarrie has simply proved something we knew all along. Whatever mask it’s wearing, underneath it the action blockbuster always looks the same. It looks exactly like Tom Cruise.