When particularly violent criminals are prematurely transferred from Young Offender Institutions into adult prisons, their files are marked with stars identifying them as troublemakers. This practice (that of being “starred up”) is one I’d never heard of before; one which seems too archaic and controversial to be true, yet depressingly is. Youths being forced to fend for themselves among hardened convicts in the British prison system is not unheard of. In fact, as one character in this film assures us, among the the incarcerated “being starred up means you’re a leader”.

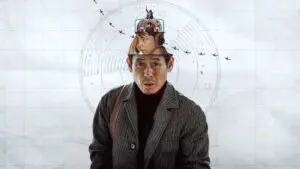

The career of Jack O’Connell has followed a similar trajectory to one of these inmates, at least in the sense of a young man a little before his prime being snatched away from his contemporaries and dropped into particularly deep water. Rising to prominence on the strength of his role as James Cook in E4’s drama series Skins, this is an actor who has rapidly skyrocketed from national television serials, one-off dramas and the occasional feature film into the very depths of Hollywood itself. He had a prominent supporting role in 300: Rise of an Empire, played the leading man in Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken, and co-starred alongside George Clooney and Julia Roberts in Money Monster. His blistering performance here, in David Mackenzie’s prison drama Starred Up, proved that he had the raw acting talent for those high-profile roles.

Starred Up‘s central character is Eric Love, a damaged and dangerous nineteen-year-old whose propensity for violent outbursts has landed him within the walls of an adult prison tough enough to make any borstal on earth look like a summer camp. Eric, however, is already an old hand when it comes to the intricacies of prison life: the demeaning and invasive induction procedures illicit barely any response; and, upon arriving in his cell, a couple of minutes is all he needs to fashion both an improvised weapon and a neat hiding place for it – all before he’s said a single word. This is excellent, wordless exposition which communicates more about a character in five minutes than many films do in their entire duration.

O’Connell lends an eerie authenticity to Eric, from his facial expressions and general demeanour, to the way he struts around with a boisterous tough-guy swagger, to how he occasionally retreats into himself, tightly coiled, like a cornered predator. That authenticity permeates the entirety of Starred Up, and while the leading man embodies it most ferociously, his surroundings and fellow actors all do their parts exceptionally well.

Filmed on a shoestring budget in one of Belfast’s disused penitentiaries, this is a raw, claustrophobic and, importantly, glamour-free depiction of institutionalization. There’s an overwhelming feeling throughout the film that of all the terrible places one might find themselves in life, perhaps the worst is within those walls.

Among those confined alongside Eric is Neville, a well-known (and widely feared) name and face on the wing, played extraordinarily well by Australian actor Ben Mendelson, who with this performance has just about cemented his reputation as the go-to guy for sleazy, haggard psychopaths. Nev is also Eric’s biological father, which is at once both the film’s most irritating conceit, and its most intriguing twist on the genre’s formula.

That isn’t to say Starred Up is immune to genre tropes; there’s still tension in the exercise yard and gym, there’s still a fight in the showers and there’s still a Mr. Big in cahoots with an openly corrupt prison governor. But there’s still a lot here which seems fresh and original: biological rather than surrogate parenthood, for one thing, but also the presence of Homeland‘s Rupert Friend as a volunteer therapist, Oliver, who believes in rehabilitation through group sessions wherein the prison’s most volatile inmates sit together and attempt to talk about, and find solutions to, their various problems.

These group scenes – which are based on screenwriter Jonathan Asser’s personal experiences working at HMP Wandsworth in a very similar capacity to the Oliver character – are where Starred Up really elevates itself above usual prison drama fare, and approaches the same territory as Alan Clarke’s legendary Scum; not just a well-made film, but a socially-conscious and important one. Asser has a tremendous ear for dialogue, and is able to communicate a lot of subtlety in what many would assume to be slang-riddled torrents of nonsense. These are believable sequences where one misjudged word is the difference between something potentially kicking off and actual physical violence, and the tension never really goes away, even as the participants begin to understand each other.

One thing I particularly admire about Starred Up is the fact it never becomes preachy, even though it’s communicating quite a clear pro-rehabilitation message. The story never stops being about Eric personally, even when the group therapy is blatantly shown to be working as a whole. As someone who has far too many friends who are either dead, in prison, or on their way to one of the two as a result of anger issues which were never properly addressed, it’s difficult for me not to develop a personal bias towards this kind of depiction – luckily there’s such a great film surrounding the potential “message” that it doesn’t really matter if I do.

Where Starred Up stumbles is during its final act, which strays a little too far away from the brutally honest but still rather grounded narrative developed throughout most of the running time, and descends instead into something greatly resembling melodrama. This is unfortunate, and could ultimately prevent Starred Up from achieving quite the same cultural resonance as the aforementioned Scum, but it doesn’t sully the experience to such an extent that this stops being an incredibly effective film. There are many, many lessons to be learned from David Mackenzie’s work here.