If you were wondering what, exactly, comes at night, allow me to be the bearer of bad news: It’s not what you think.

It’s not zombies, even though It Comes at Night borrows a lot of visual inspiration and filmmaking language from your typical post-apocalyptic undead hoedown. It isn’t a ghoul emerging from the forest or a serial killer stalking the hallways, even though the cabin in which most of the film is set is situated right in the middle of the woods, and eerily barricaded against intruders. It isn’t even the nebulous viral plague that has wiped out a good portion of the near-future population; the sickness might blacken the eyes of the infected and demand that they’re immediately killed and burned, but it can’t penetrate the sealed rooms of the cabin, or the gasmasks of its occupants.

So what comes at night? The answer is really what distinguishes this film from a thousand other boilerplate genre exercises. It’s paranoia. It’s fear. It’s the creeping understanding of how hopeless and oppressive life has become; the kind of destructive, disruptive neuroses that, during the day, are staved off by the relentless minutiae of survival. What’s admirable and novel about It Comes at Night is that it uses the familiar trappings of the genre to deconstruct it. The inciting incident might be the apocalypse – albeit a low-key, realistic interpretation of it – but the story it wants to tell is about the breakdown of social order. The overarching theme is that no matter how well you prepare for it, the end of the world will still fuck you up.

It Comes at Night is the second film from Trey Edward Schults, who became a critics’ darling with 2015’s Krisha, which was another horribly downbeat familial drama with a twist of autobiographical DNA. This film, by design, is more tense and absorbing, but the genre-mandated pickle these characters find themselves in feels more constricting than the dizzying vortex that Krisha spiralled into. It’s tersely-written and well-acted, but never quite manages to completely transcend the conventions it’s built atop of.

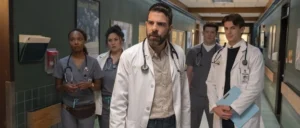

Joel Edgerton (who’s the film’s executive producer) plays Paul, the traditional no-nonsense Survival Dad who grumbles through his beard about rules. He’s holed up in his woodland cabin with his wife, Sarah (Carmen Ejogo), and their 17-year-old son, Travis (Kelvin Harrison Jr). Paul’s beard explains things like how to dispose of bodies riddled with plague sores – the first is Bud (David Pendleton), Sarah’s father – and that the cabin can only be entered and exited through one door, a red one at the end of a gloomy corridor that must remain locked and bolted at all times.

What Paul’s beard doesn’t expect is that another beard might break in, this one belonging to Will (Christopher Abbott), another desperate husband and father looking for supplies. Will has livestock and tinned food to trade for Paul’s water and shelter, but also a wife, Kim (Riley Keough), and a toddler son, Andrew (Griffin Robert Faulkner), who, in the interest of cooperation and companionship, all move into Paul’s cabin.

You might be surprised to learn that this doesn’t go exactly as planned. Goats are useful, and two three-person families make for better board game nights, but a teenaged lad in close proximity to someone’s saucy wife is never a good idea; Paul’s place has an attic which is ready-made for spying, and when Travis sneaks up there to listen to Will’s family settle-in, you expect what’s coming at night to probably be him. Pretty quickly what seemed like a mutually beneficial arrangement collapses into an uneasy existence of mistrust and suspicion. The horror in It Comes at Night is of the slow-burning psychological variety, as Will and Paul – their very names redolent of Old Testament ferocity – go beard-to-beard over increasingly contentious issues.

To say any more would be spoiling the film’s carefully-measured servings of suspense, which eschew twists and jump-scares in favour of tragic inevitability. It’s a taut bit of work, this, and it deserves an audience for its commitment to bleakness, if nothing else. That isn’t to say it’s entirely without flaws. It being so hemmed-in by genre convention ultimately prohibits it from achieving a dramatic depth that would have allowed it to transcend its foundations or at least properly deconstruct them, while it’s relatively short length and the lack of any outlandish elements leave the overall feeling one of slightness and inconsequentiality.

Still, It Comes at Night held me all the way through; it’s a tight and impressive exercise in psychological suspense that uses our expectations of post-apocalyptic survivalism to suggest that perhaps the beardy micromanaging control-freaks who usually function as the heroes in these stories might actually be the guys we should fear the most.

Who’d have thought it?