Adapted from the non-fiction book of the same name, The 15:17 to Paris tells a tale of real-life heroism starring the three American men – Spencer Stone, Alek Skarlatos and Anthony Sadler – who foiled a terrorist attack. Directed by Clint Eastwood.

The 15:17 to Paris is an incredibly bizarre film – the 36th to be directed by Clint Eastwood, but the first of his 50-year directing career to feel like a workplace training video.

The 15:17 was a train going from Amsterdam to Paris in August, 2015. Aboard were three Americans; friends since childhood, two of them in the military. Airman First Class Spencer Stone, Oregon National Guardsman Alek Skarlatos, and college student Anthony Sadler. Also aboard was a Moroccan, Ayoub El Khazzani, who emerged from a washroom bristling with weaponry and attempted to kill the passengers.

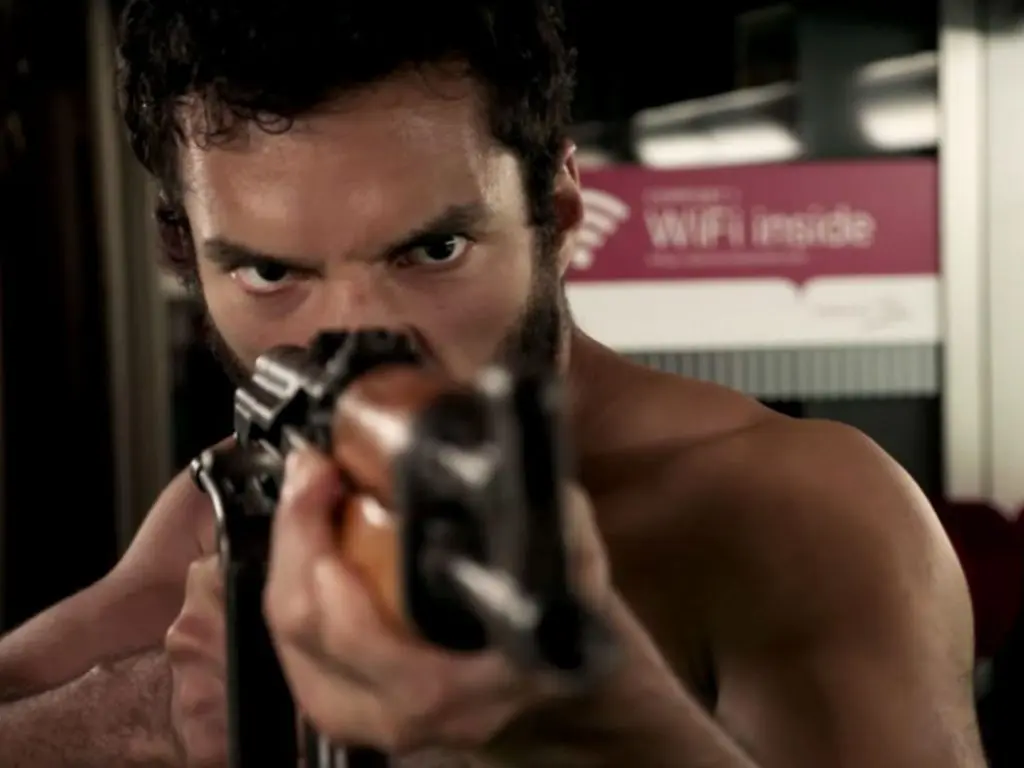

Stone tackled Khazzani and held him in a chokehold while being repeatedly slashed and stabbed with a knife. Alek and Anthony, along with a 62-year-old British businessman by the name of Chris Norman, battered the attacker into unconsciousness, both with their fists and the butts of weaponry he had dropped. They kept him alive until the train was able to stop. For their bravery, the four men were made Knights of the Legion of Honour by French president François Hollande.

This is a great story of real courage. But unfortunately I’m here to report that Eastwood’s film – which was adapted from a book co-written by the trio, along with Jeffrey E. Stern – is a spectacular failure of filmmaking. So much so, in fact, that I’m not sure I’ve ever seen anything else quite like it. It’s grubby with the meddlesome fingerprints of the kind of eccentric artist that Eastwood has made a career out of not being. The no-nonsense director, who is renowned for shooting quickly, efficiently, and only doing one or two takes, here devotes roughly three-quarters of a feature film to scenes that have absolutely no bearing on the larger plot, performed by actors who have never been in a motion picture before.

The decision to cast the three American heroes as themselves was a bold one, and it says a lot about The 15:17 to Paris that their performances are the least of the film’s problems. Their re-enactment of the wild action aboard the train takes up maybe 15-20 minutes. Call me cynical, but I think that’s the part of the story people are interested in. They’re not here to see painstaking recreations of the three friends meeting in middle school, where they bonded over their mutual rebellion against Christian authoritarianism. Spencer Stone’s training for and taking of Air Force tests is not entertaining. And the tortuous scenes that take up the bulk of the film, that see the trio vacationing around Europe, taking selfies, going to clubs, and drinking beer in various restaurants, are about as involving as a gap-year student’s home videos, only must less naturalistically performed.

In the last decade or so, Eastwood has been fascinated with non-fictional heroism. His boilerplate style always suited facts. That he frequently worked with some of the biggest stars in Hollywood – Tom Hanks in Sully, Morgan Freeman in Invictus, Bradley Cooper in American Sniper – helped to offset his lack of patience. His decision here is admirable in a way that attempting to build a house out of matchsticks would be. You can respect someone for trying it, but in the back of your mind, you can’t understand why they haven’t realised what a bad idea it is.

Stone is determined early on, presumably by Eastwood, to be the most interesting member of the trio. The other two get given some screen time, but Eastwood doesn’t delve into their upbringings in the same way. Skarlatos is also in the military, but he’s wooden, to put it mildly, and less of a screen presence than his towering, goofball buddy, so he’s kept mostly off-screen until he joins the others as an adult.

Stone it is, then. He’s a surprisingly not-terrible frontman. No depth or nuance, of course, because that comes with training and experience. But he has a likeable, laidback charisma. He also, and I think this was important to Eastwood, regularly talks about destiny, and having a greater purpose. His mother (played in flashbacks by Judy Greer) is religious. His friends mock him for it, but there’s a sense that we, as the audience, are supposed to believe that God has something exciting planned for his future.

Some of the details scattered throughout the film’s assorted montages and vignettes are important to the eventual attack on the train. Stone learns Jiu-Jitsu. Stone learns how to treat a neck wound. But most of The 15:17 to Paris is one stilted dialogue scene after another, the three buddies hanging out and ordering food in restaurants while robotically cycling through bits of dialogue. That sense of an iPhone travelogue is most prominent here, but you also get the sense that this isn’t even a particularly good holiday.

The action, when it arrives, is handled vividly and convincingly. What was problematic before, that eerie feeling of being right there with the boys, becomes a fairly potent dramatic tool. But this is a relatively simplistic, straightforward incident. It doesn’t last long, and once it’s over, you immediately wonder why we needed an entire movie to build towards it. The whole thing would have been better served as a documentary. Trying to craft a dramatic feature-film around the incident simply results in a tale of genuine heroism being told remarkably poorly.