Summary

In The Station, a first-person sci-fi narrative game, players explore an abandoned research ship in an attempt to find its missing crew.

The titular station is the Espial, and it’s orbiting a planet of violent, warring aliens. Aboard are three scientists, whose jobs are to observe the newly-discovered extraterrestrials in stealthy secrecy. No such luck. Not long into the cataloguing of this mysterious civil war, a malfunction disables the Espial’s cloaking systems, the aliens catch them snooping, and the station goes dark.

You, the player, are a specialist who arrives on the scene to assess the situation. To what extent is the mission fucked? Are the scientists dead? Your three primary objectives are to find each of them, but you’re never really briefed about where they might be or what might have happened to them. As usual in games such as The Station, the answers are to be found in bitten-off audio logs and emails and documents, all scattered liberally around the Espial’s gloomy but oddly luminescent interiors.

So far, so familiar. And as a first-person sci-fi narrative game with snatches of horror and a gradually-unfurling mystery, I could quite easily bury The Station under comparisons to games like Dead Space, Prey, Soma and Tacoma – and my reviews would rhyme, apparently. But I’m better than that, and so is The Station, even if it isn’t quite as good as I might like.

It’s better than first impressions suggest, at least. The opening cinematic is blessed with hilariously stilted voice acting, and the player-character’s first job upon arrival is to plug an errant power cell back into a door. Ugh. I confess to being a little worried at this point, so much so that I found myself wondering if I’d left the game on the title screen for long enough to void Steam’s refund policy. Luckily it only took a quick traipse through The Station’s lobby area to sweep aside my scepticism. An audio log revealed that the crew of the Espial are well-voiced, and some incidental details – a table strewn with playing cards, scattered work notes and such – gave me an impression of a place that might have been inhabited; that might, in fact, still be inhabited.

That’s the hook. The three missing crew members are Mila, the captain; Aiden, an engineer; and some kind of obnoxious researcher by the name of Silas. Early on, you turn around to see a person in a spacesuit across the room. And if you’re anything like me, that’ll be enough. One of the crew? One of the aliens? Dramatically, it doesn’t matter. The only thing that does is that whatever cosmic mess you’ve been sent to clear up is evidently still on-going.

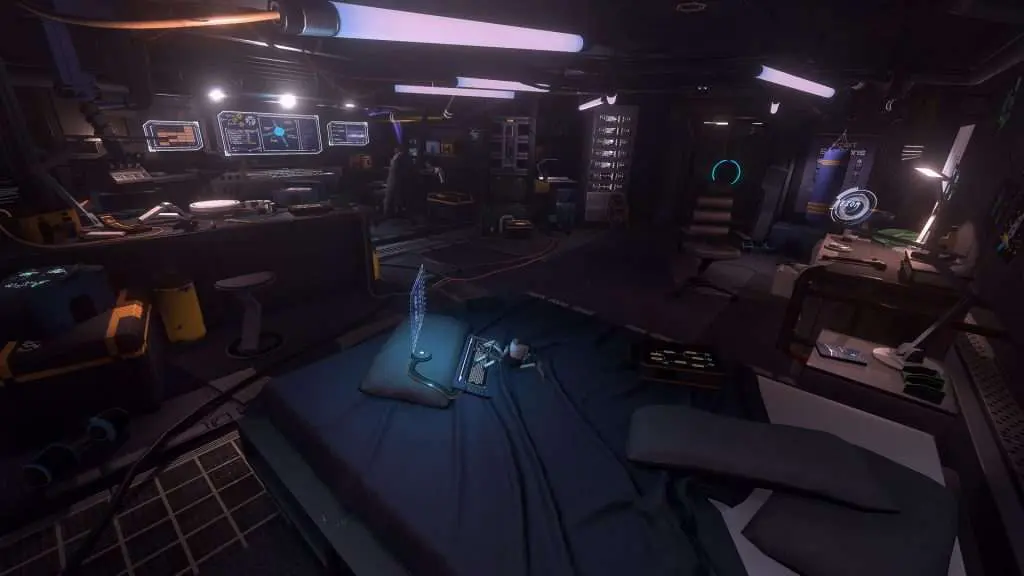

As you schlep through the ship’s innards, you get to know the folks you’re looking for. You poke around in their bedrooms and work areas; read their emails and listen to their recorded rants and conversations. Once you start to get a sense of why these three took on such a crazy mission, The Station starts to work as intended. You’ll chuckle at the pettiness of Mila leaving snide remarks about Silas in reports. It’s as if you’ve stepped into a tiny, contained slice of society, only all the people winked out of existence moments before you arrived.

The Espial, like any interior, is divided between corridors and rooms. Only the rooms are interesting, but you see far more of the dour tunnels that knit them together. There’s nothing interesting about corridors, I know, but here, nothing interesting happens in them either. They all look alike; rows of doors, some with blue lights, which are unlocked, and some with orange lights, which are locked, and the closest blue-lit door is the one you need to open, almost always. Inside the room, there’s life. All the interesting character development and world-building lives in those spaces, as do the game’s rudimentary puzzles. It’s easy to feel like when you’re not in a lab or a hanger or an office that The Station is held in stasis, waiting for you to wander back into the plot.

That plot only takes about an hour to run its course, which I’d be remiss not to mention. Ordinarily I don’t concern myself with “value for money”, which is too subjective an issue to worry about, and usually irrelevant to criticism anyway. But a 60-minute narrative game with no replay value retailing at a tenner feels like being mugged.

It’s just as well, then, that The Station has such a terrific ending. It’s ballsy enough to be worth the price of admission on its own, and once the game’s rougher edges start to grate, you’ll be thankful that the final five minutes are the best and that it buggers off before becoming properly annoying. It might not last long, but it’ll probably stick with you for a while, and mostly for the right reasons.