Summary

Better than you remember it and still worse than it needed to be, Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace is a so-so slice of science-fiction that unfortunately had no business in a galaxy far, far away.

Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace is part of the current Star Wars canon. You can check out the entire timeline by clicking these words.

Because I often worry that I’m not annoying people quite enough, I’m constantly thinking up new and creative ways to irritate our loyal readership. Thus, here’s a review of Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, a film which I actually think is alright. Yes, I know that’s neither new nor creative. But you’re pissed off, aren’t you?

Of course you are. The Phantom Menace is one of the most reviled films in cinematic history; not entirely because it’s bad, but because it came after almost 16 years of anticipation following one of the finest – nay, let’s be frank, the finest – film trilogies of all time. And then it took an overlong, steaming, midi-chlorian-infused piss over that decade-and-a-half of expectations.

Luckily, following the release of Star Wars: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi, a not-insignificant contingent of die-hard fans have started to look back on The Phantom Menace a bit more favourably, their fervent hatred of Disney and women having forced them to retroactively declare the prequels the best things ever because they were faithful to George Lucas’s “vision”. And if, when you read that last word, you imagined me performing elaborate scare quotes and rolling my eyes like I was having a seizure, then you, young padawan, may well be strong in the Force.

But I thought The Phantom Menace was alright long before that – and if it makes you feel any worse, I found The Last Jedi to be a daring nigh-masterpiece second only in the Star Wars mythos to Star Wars: Episode V –The Empire Strikes Back, which perhaps shall never be bettered by anything, least of all a film in its own universe.

My long-held theory that The Phantom Menace would have been quite favourably received and promptly forgotten about were it not a Star Wars sequel seems truer today than it ever was, especially now that people are returning to it in their Disney-smiting desperation and seeing what I saw all those years ago – it’s a so-so sci-fi movie with an overlong second act, some extraordinarily irritating characters, and some bone-headed narrative decision-making, but it’s otherwise alright. No, not “good”, in the traditional sense, but the idea of enshrining The Phantom Menace as some kind of life-ruining travesty of moviemaking is somewhat absurd considering it isn’t even the worst Star Wars movie.

I’ll concede, though, that an opening in which the laser-sword-wielding heroes are led to a waiting room while the insidious villains video-conference about the legalities of invading Naboo isn’t exactly helping my case. As a matter of fact I’d argue that a pulp space-adventure like Star Wars has no real use for a Trade Federation at all, much less a Republic Senate, and most particularly not one which grants relatively easy membership to the one-note comic-relief sidekick character whose singular defining characteristic is stupidity.

That could be the point, of course, but I suspect not given the lack of self-awareness Star Wars exhibits elsewhere. The opening of The Phantom Menace, then, is not very good, although once it gets going it is slightly superior to the film’s second act, where our intrepid heroes venture the barren desert planet of Tatooine to haggle with a junkyard dealer over faulty engines as the fate of the galaxy, we’ve been told, hangs precariously in the balance.

There is a reason for all this, and his name is Jett Lucas, the adopted son of George, who was around the same age as Jake Lloyd’s Anakin Skywalker when the film was being made. It should come as no surprise then that the plot, the first George had written since his 1983 divorce from his wife, Marcia, concerned the discovery of a miracle child who was passed from his biological mother to an adoptive parent. From this we can safely infer that Lucas’s “vision” was the assuaging of his obvious divorcee and single-parent anxieties; the accommodation of which required the substantial rewriting of galactic history to postpone every interesting major event in favour of having the future Dark Lord of the Sith cry when he is wrenched from the arms of his mother. This self-serving impulse eventually proved ruinous to both the prequel trilogy and Lucas’s reputation, and Jake Lloyd is now a schizophrenic criminal living in a psychiatric institution.

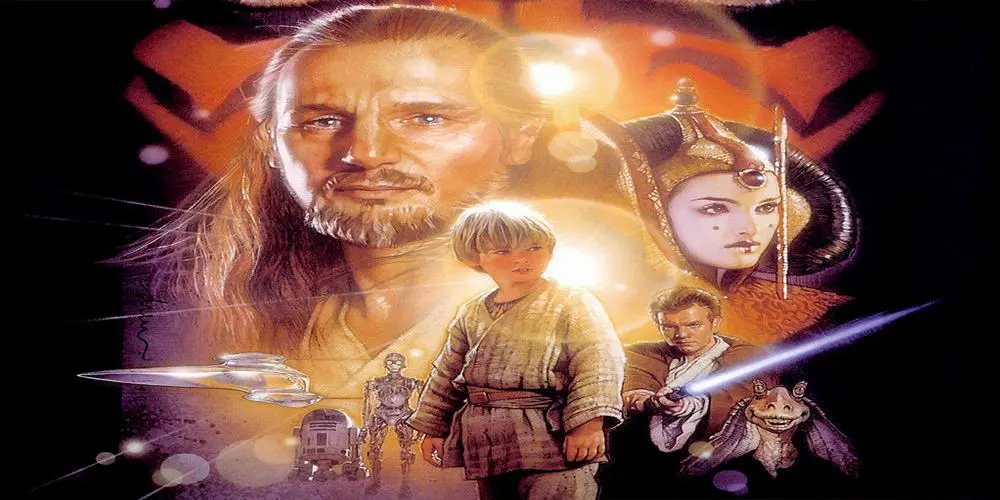

The new starting point, with its bumbling frog-men and whimpering children and soggy second acts, was one from which the prequels never really got going or, indeed, properly recovered. This is why it’s helpful to take The Phantom Menace on its own terms. Consider, for instance, its visual design, which, some dodgy CGI and that unspeakable Yoda puppet notwithstanding, is every bit the equal of the Original Trilogy’s in terms of imagination. Indeed the film has several great-looking locations, costumes and aliens, solid cinematography and technical direction, striking and colourful art design, and the best-choreographed lightsaber dual in the series scored to some of composer John Williams’ finest work. This remains true even if you admit that the pod racing sequence lasts at least one lap too long.

Consider also, if you will, the presence of Liam Neeson, who has at various points in his career played Qui-Gon Jinn, his Jedi Knight character here, as well as Oskar Schindler, Ra’s al Ghul, Zeus, and Bryan Mills, making him the de facto expert in doomed father figures. His death at the hands of Darth Maul (Ray Park), the series’ second-most iconic villain, is the only moment in The Phantom Menace with any sense of dramatic weight. His panted final words do more for the audience’s stake in the future of Anakin than any of the boy’s thoroughly misguided feints at innocence, which George Lucas couldn’t write and Jake Lloyd couldn’t perform, and which made no real sense for a character fated to become a robotic, asthmatic executioner regardless.

I don’t think about The Phantom Menace too often, as I’ve confined it to a part of my memory that I rarely have any use for. But when I do I think how it is a product not of George Lucas’s “vision” but of his fear; his fear of fatherhood, of his legacy, and I think how easily it might have been fixed, to use a term less grandiose than “saved”, by simply making Anakin Skywalker older and less cherubic. And fear is the reason, no doubt – what else might compel a man – a myth-maker of the old, Flash Gordon style, no less – to attempt an explanation of “the Force”, that nebulous tool of narrative convenience that nobody in their right mind ever needed or wanted an explanation for. The answer is now as it always was: because without the Force, there would be no galaxy far, far away, and the world would be worse for its absence. Some things require no explanation beyond being the product of a big, ambitious imagination.

Of all the things George Lucas came to misunderstand about the universe he himself created, the one that bothers me most is not that he forgot where it was going, but that he forgot where it came from.