The Rocky franchise is due to welcome it’s eighth instalment this month with the release of Creed II. Throughout its 42-year life cycle, Rocky has always represented the American dream: a working-class guy who life had seemingly passed by reaches the summit of the sport of boxing through determination, hard work and guts. However, that is not the only social movement that we can link to the film’s long narrative. Throughout its history, Rocky has dealt with issues such as legacy and fatherhood, (an awkward attempt at) racial politics, social mobility, and even managed to bring down the Soviet Union. Let’s have a look at how the series has evolved and how it’s many incarnations have dealt with and reflected shifting attitudes in American politics.

Rocky (1976) – The American Dream

This movie so strongly tells the fable of the American dream that even its production is one of the great rags to riches tales in filmmaking. Stallone, struggling to make a living as an actor and with only $106 in the bank, turned down a reported fee of $350,000 for his script about the Italian Stallion’s improbable rise because the production company planned to cast someone else in the title role. Instead, Stallone took an unpaid writing credit and worked for scale in exchange for the starring role in what would go on to win that year’s Best Picture award at the Oscars (it also picked up further awards for Best Director and Editing).

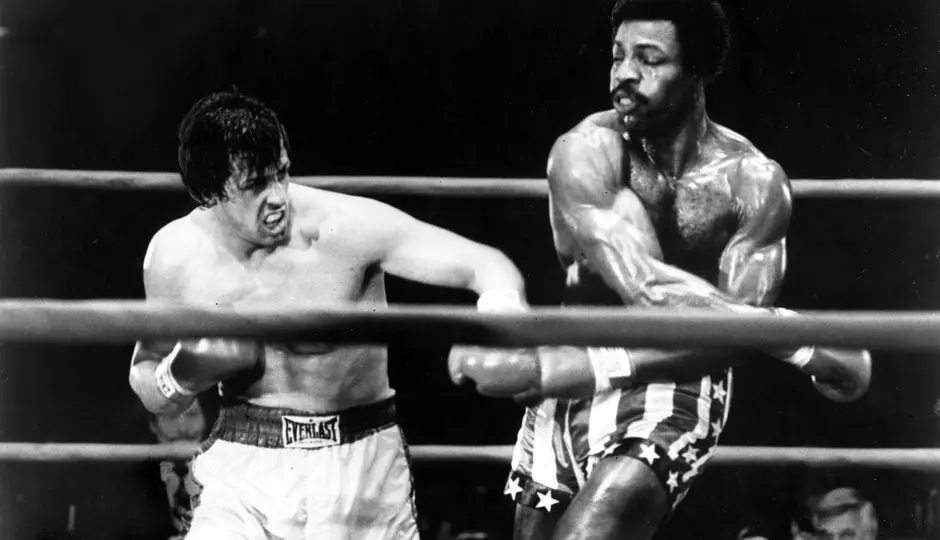

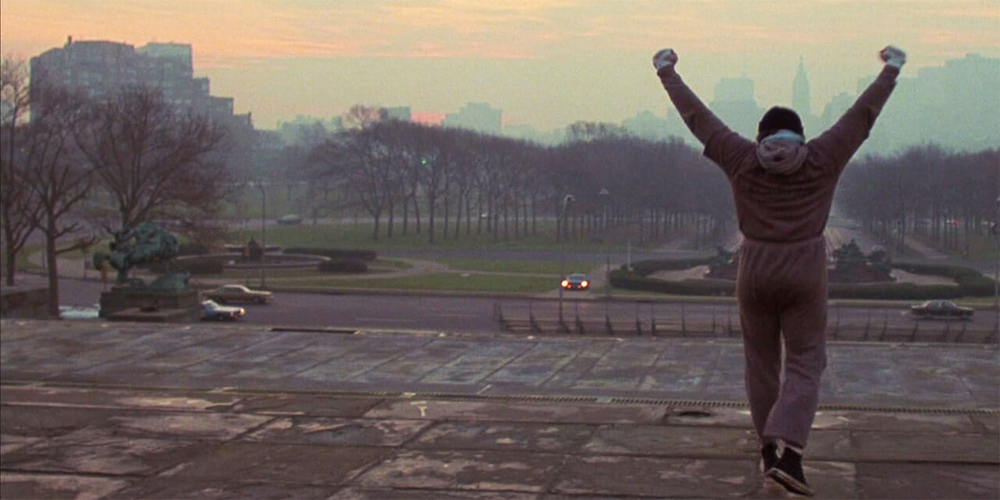

The film itself tells a tale of the working class Rocky Balboa, a talented but unfulfilled boxer who supplements his income collecting on behalf of a local gangster. He is going nowhere; that is until he is selected by the Heavyweight champion, Apollo Creed, as his next opponent. The fight is a PR stunt designed to show the public of the power of the American Dream – anyone can make it (at one stage Creed literally dresses as Uncle Sam!). What follows are a number of set pieces that would come to provide the series with so many of its iconic features – the training montage with the iconic jog through Philadelphia, the famous music, the unintelligible drawl, and of course the incredible fight choreography. Rocky narrowly loses the fight but emerges the moral victor (an echo of America’s attitude to the Vietnam war, perhaps?) Released in the shadow of Vietnam and the Watergate scandal Rocky gave American audiences someone simple, relatable and easy to root for.

Rocky II (1979) – Fragile masculinity

Following his unlikely heroic defeat, Rocky is now a national figure and is celebrated for his performance. Following doctor’s orders, Rocky retires from boxing and decides to turn his change in fortune to his advantage. Meanwhile, the humiliated Apollo Creed is desperate for a re-match to help him recapture some measure of self-respect.

Rocky struggles to adapt to his new celebrity and at first spends big; he buys a nice new house for his pregnant wife, he buys a number of eye-catching expensive items – all of which are really gaudy and underline the film’s attempt to illustrate Rocky as being hopelessly naive. When he gets the opportunity to make a living appearing in TV adverts we learn that Rocky is totally illiterate and is unable to read from the cue cards. Under increasing financial pressure and having been totally emasculated, Rocky decides to enter the ring against the doctor’s orders.

The film picks up the pace in the final third and again the climactic fight scenes are electric. However, Rocky II is largely a bloated, overly long sequel that somehow makes everyone unlikable. Apollo Creed is a bad loser who taunts Rocky; Rocky risks his health and life to protect his masculine pride (“don’t ask me to stop being a man”) despite what the consequences may for his family, and Paulie (Rocky’s brother-in-law) is jealous and mean-spirited (more on Paulie later). The one prevailing theme of this film is how unself-consciously it uses wounded male pride as the motivation for all its action, and does so seemingly because of how men were “supposed to” act in the late 70’s.

Rocky III (1982) – Here come the 80’s

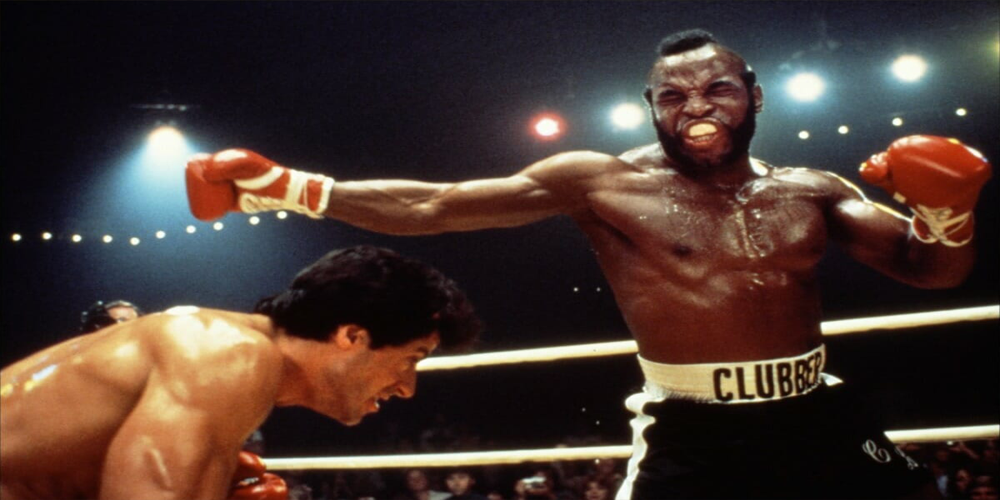

After the Grey, bleak political 1970’s came the colourful, consumer-driven, body-oiled 1980’s and boy does Rocky III tick all the 80’s boxes. After it’s attempt at introspective drama in Rocky II, the third instalment in the series changes gears and gives us a very different and much needed change in energy.

Riding high on success following his victory over Apollo Creed we meet Rocky living the good life. His family is wealthy and happy and he is winning a succession of easy fights. That is until he encounters Clubber Lang, played by Mr T. Lang is hungry and motivated and crucially has “the eye of the tiger”. He defeats Rocky easily. Following the death of his trainer, Mickey, Rocky is taken on by former rival Apollo Creed who helps him get back his edge.

This is one of the more entertaining entries in the series and the fact that it appears to deliberately steer away from tackling social issues (aside from its super ham-fisted attempt to distinguish black boxers from white boxers with a visit to a gym in South Central LA) in itself reflects a trend in American society at the time. The film is exaggerated in every way, echoing the excess that for many characterised the decade. The actors are sprayed down in every shot so their muscles glisten, the music moves away from the jazz inspired soundtrack of the first two to an 80’s guitar-led soundtrack (“Eye of the Tiger” the most memorable song), the camera movement is kinetic with loads of quick cuts, especially compared to the first film, and finally, most 80’s of all, is Stallone and Carl Weathers in half t-shirts. In the end, we have almost moved to a full-on buddy movie when Rocky and Creed face off to settle their score one last time.

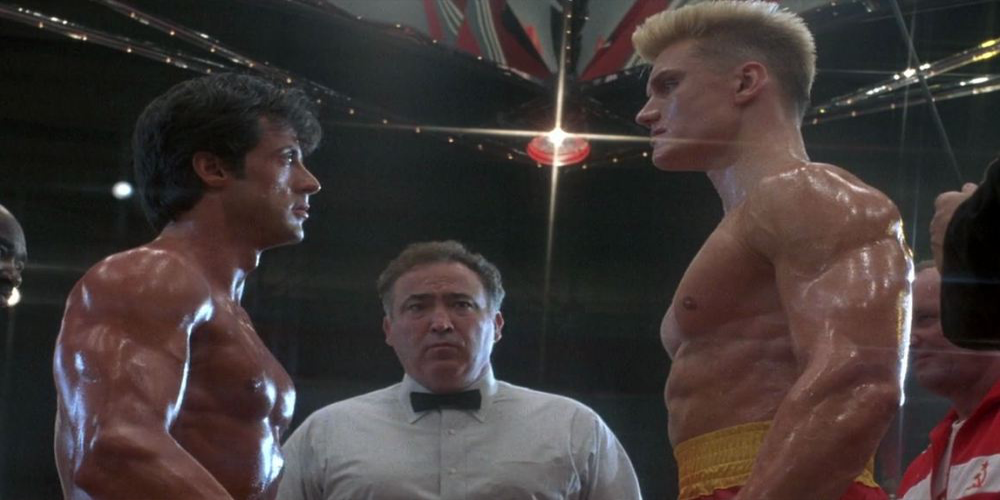

Rocky IV (1985) – Bringing down the wall

Rocky IV is a one off viewing experience. It is the most nakedly and unashamed piece of pro-USA propaganda you will see. Made at the tail end of the Cold War, Rocky once again comes out of retirement to avenge the death of his friend and former rival Apollo Creed at the hands of pantomime villain, Ivan Drago.

Rocky moves to the Russian countryside where (in the greatest training montage of all time) he grows a beard and trains by chopping logs in the snow and doing sit ups in a barn. This old fashioned and “back to basics” approach is juxtaposed with the cold, impersonal Drago being almost created in a lab where he receives regular steroid injections from a team of men in lab coats who measure his every move.

At the end of the now obligatory showdown, Rocky manages to turn a hostile Russian crowd to his favour due his spirit and courage in the ring. After finally defeating the walking, talking metaphor for Communism, Rocky addresses the crowd with a speech encouraging everyone to get along, which provokes a round of applause from the crowd with even Gorbachev joining along.

Rocky IV is the most outlandish film in the series. Rocky is once again the hero but this time his challenge is not to deal with his own issues of wounded pride or loss; this time his challenge is to take on the Soviet Union to a John Cafferty soundtrack. God bless America.

Rocky V (1990) – Post-Cold War Blues

After the brutal bout with Drago, Rocky is left with permanent brain damage and is forced to retire from boxing (where have I heard that before?). We also discover that Paulie had given power of attorney to a crooked accountant who has lost all of their money. The family goes from riches back to rags and we are left back where we started, in the ghetto of Philadelphia. This film reunited Stallone with Avildson, the director of the original film, but this outing for Rocky contains none of the muted optimism of the first.

Once again having to come to terms with the fact that he is not able to provide for his family and missing fighting, Rocky decides to neglect his son (played by Stallone’s real life son) and train a young up and comer by the name of Tommy Gunn (seriously). Tommy eventually betrays his mentor after being perniciously influenced by the Don King-esque promoter who is trying to get Rocky back in the ring. Eventually, Rocky and Tommy face off in a street fight to once and for all settle the argument of who is the better fighter?

The unintentional subtext to this film is a metaphor for post-Cold War America – what do you become when your foes are all defeated and there is no one left to measure yourself against? Do you simply retire or is there another way to continue to have relevance?

Rocky Balboa (2006) – Grief and the shadow of the past

After a 16 year gap, Rocky returned to our screens for one last bout. In Rocky Balboa, we catch up with Rocky living in the past, regaling diners in his restaurant with tales of his glory days. Adrian, Rocky’s wife, has passed away, and Rocky is still clearly grieving for her. He also has a strained relationship with his son, who feels as though he lives in his father’s shadow. With seemingly nothing more to live for and enough in the tank for one more go around Rocky re-enters the ring. Meanwhile, the current Heavyweight champion is facing criticism that he is not loved by fans of boxing, so in order to bolster his popularity, an exhibition fight with the Italian Stallion is lined up.

On paper, the idea of 50-something Rocky fighting again seems ludicrous, but the script somehow makes it work. Rocky is not seeking glory; simply hoping to feel alive and relevant again, and boxing is the only thing he ever knew. A lot of the original production team returned for this one and the film looks and feels like the original Rocky movie, with Stallone writing and directing and Bill Conte returning for the score; there is a clear throughline from the series’ beginning. Stallone’s performance is understated and subtle which gives the film unexpected heft.

This is a film for the mid-2000’s. Just before the global financial crash but with the Iraq conflict still in full swing, this film was made with tempered optimism that somehow an ageing superpower still had one last good fight in him.

Creed (2015) – Passing the baton

The son of Apollo Creed, himself an aspiring boxer, seeks out Rocky in the hopes that he might train him and mentor him. Initially reluctant, Rocky takes him on and passes on his experience to the next generation.

A surprise hit, Creed cleverly reinvents the series by refocusing the story on a new lead. Adonis Creed, played by Michael B. Jordan, never knew his father and is the son of his mistress. Donny grows up feeling alienated from his father’s legacy and has something to prove.

One of the things that makes Creed so interesting is that this is the first time the series has been helmed by new creative talents. Ryan Coogler sits in the director’s chair this time and along with his regular collaborator Michael B. Jordan we are introduced to a different world. The fact that this film is directed by a black director whose previous work, Fruitvale Station, tackled some hard-hitting social issues and his next film (Black Panther) would help to redefine comic book movies for black audiences gives Creed something else, and opens the world up to new perspectives. When set in contrast against the Black Lives Matter campaign this marks an exciting trend when black filmmakers and actors can take existing intellectual property and continue to develop the canon whilst adding new voices to a series. This could potentially open the ground up for other franchises to follow suit (hey James Bond!).

As with any long-running film series the instalments tend to reflect the times in which they are made. With political division, social unrest, economic uncertainty and a very socially conscious filmmaker at the helm, it will be really interesting to see what Creed II tells us about America today when it lands later this month.