Today, over a year after the unacceptably popular six-episode first season of Netflix’s Neo Yokio, a long-awaited continuation of the series has arrived on the streaming platform in the form of a Christmas Special entitled Neo Yokio: Pink Weekend. I haven’t seen it, and I likely won’t, and thanks to the vague management structure here I’m in the process of forcing someone else to watch it instead. In the meantime I should tell you why I find the whole thing utterly insufferable and deserving of scorn.

Created by Ezra Koenig, lead singer of Vampire Weekend, and starring Jaden Smith, the androgynous pseudo-philosopher offspring of Will and Jada, Neo Yokio is a soulless and grating pastiche of varied anime influences and a disgracefully self-indulgent celebration of Jaden’s enigmatic and nonsensical public persona – especially his dopey Twitter account, where he seemingly just types whatever rubbish he’s thinking at the time and assumes him capitalising every letter of a sentence lends his inane stream-of-consciousness babble some kind of profundity.

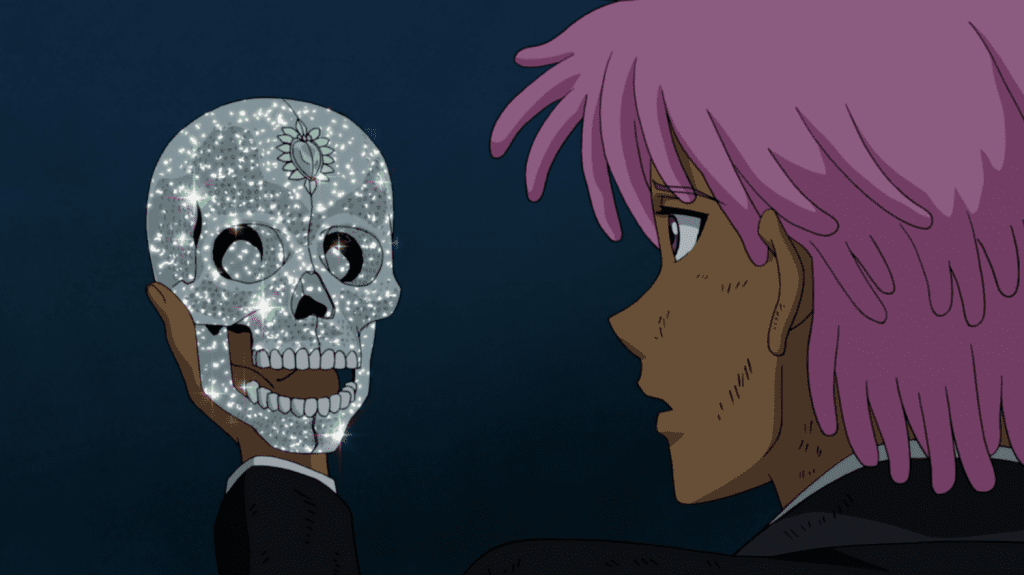

Neo Yokio includes talented storyboard artists and actors like Jude Law and Susan Sarandon in voice roles, but it has no sense of soul or aesthetic identity; it’s just a hodgepodge of influences and ideas held together by the sheer adhesive force of pretension. The twisted version of New York that serves as the show’s setting is the kind of luxury-obsessed fantasia that someone born and raised in absurd privilege might envision. It makes sense that Kaz Kaan, Smith’s character, is the wealthiest and most eligible bachelor in this place, a fact about which he never ceases to complain in his nasally monotone. He is also ministered to by robot butlers and has demon-exorcising powers, and the explanation for both of these things is simply, “because anime.”

Neo Yokio mistakes surface-level lip-service and mimicry for an appreciation of the form, but it never plays like anything other than a parody of it, despite everyone involved in its creation insisting that the thing is earnest and sincere. The same can be said about Smith’s bizarre public identity, which has a sincerity of its own; a commitment to the espousal of strange, nebulous “wisdom” that means nothing but nonetheless defines him purely by virtue of him believing it to be truth. Because Neo Yokio communicates exclusively in his disinterested voice, and revolves entirely around his self-centred, narcissistic avatar, it lives in that same space between genuine delusion and obnoxious social experiment.

Neo Yokio: Pink Christmas arrives on the same day as The American Meme, a feature documentary about social media “influencers” who have cultivated entire lifestyles and personalities purely for affirmation from brainwashed sheeple. Smith, as an eccentric artist, would have fit into that crowd, but in some ways he has grown beyond the confines of the “influencer” definition. His carefully-constructed image isn’t just contained within selfies and brand promotions, but transplanted into actual creations. He clearly isn’t stupid. But he hasn’t yet realised that his made-up skate-philosopher character doesn’t, and can’t, work in fiction. Kaz is an abstract construction; the reflection of an already-projected image. He can’t be rooted for on the same level as a human being, because he isn’t even based on one, and he can’t fit seamlessly into a world, even one created to accommodate him, for the exact same reason.

There’s a chance that Neo Yokio would work better if it was self-aware, and if it attempted to satirise its own obsessions with status and materialism. It would also work better if it ever gave the impression that it truly understood either the appeal of the strains of anime it consistently apes or the arts and philosophies it pays lip-service to. But it does none of these things. Instead it continuously circles the same drain of artistic excess, revisiting plot points and ideas that it believes are interesting but that are quite clearly not, and it never amounts to anything beyond a love letter to an ever-evolving digital culture that will, in no time at all, have moved beyond Smith’s algorithmically-constructed idea of what personhood really means.

Still, Merry Christmas and all that.