Summary

Smaller and Smaller Circles is a sharply produced and acted crime drama, pitting two educated priests against a child killer and bureaucracy. The first police procedural thriller from the Philippines, but slower than most, to mirror the slow progress.

Smaller and Smaller Circles is a crime drama from the Philippines; reputedly the first. It is based on the 2002 novel of the same name by Maria Felisa H. Batacan, which was similarly the first novel of its kind from the Philippines. I’ve not read the book, though I understand the adaptation is very close (some of the awards the film has won have been for the adaptation); nevertheless, I’m here at this keyboard to tell you about this fascinating film.

The crime at the heart of Smaller and Smaller Circles is a series of child murders; not simply murders, but each mutilated in the same way, and dumped unceremoniously in a scrap heap. It’s not the crime itself which is particularly interesting, though, but the way it is used to make some rather pointed comments about Philippine society. The main issue the story explores is that of class divide: the child victims were from such poor backgrounds that not only did the police not register when the number increased, but they had no interest in investigating either. The boys were discarded by the killer and largely ignored by everyone else, a similar view of lower classes to that presented in The Cannibal Club.

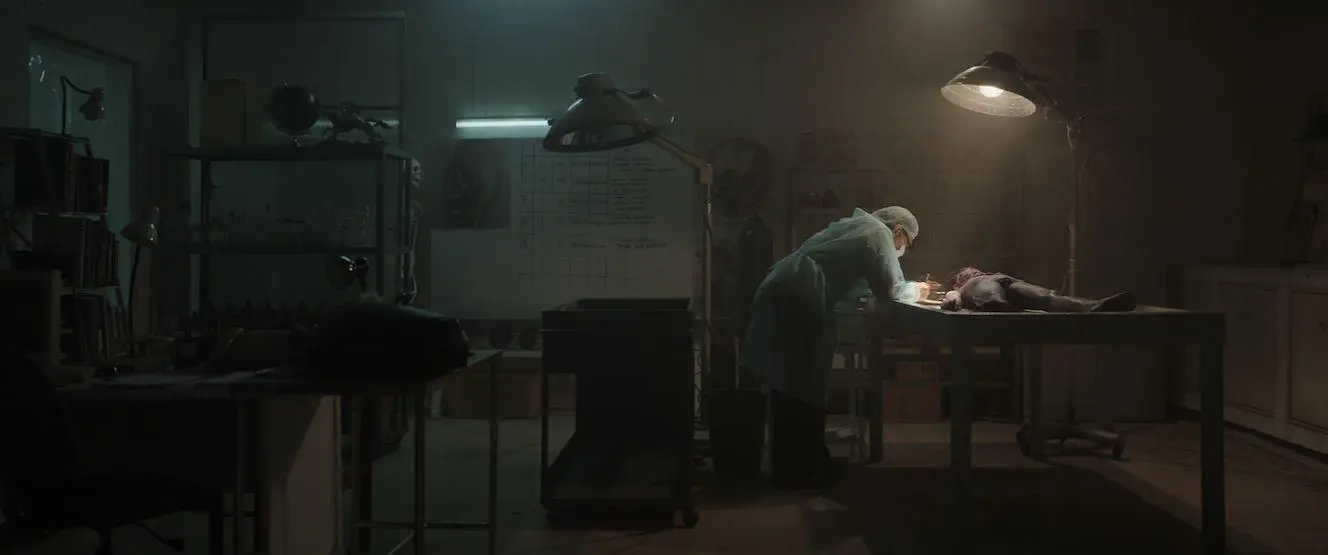

Because the police don’t take the deaths seriously, the only people who show any interest in pursuing any investigation (quite unofficially) is Father Gus Saenz, the forensic anthropologist, and Father Jerome Lucero, his assistant. They are both priests, as well as scientifically trained, and apply some care and humanity to the bodies which arrive on their table: they see them as children whose parents may be missing them, parents who deserve to know what’s happened.

Saenz (Nonie Buencamino) and Lucero (Sid Lucero) have to navigate their way through this mentality of not caring, picking up a couple of allies along the way. Gradually zooming in on where clues take them is made even more difficult when faced with corruption and political maneuvering in the church too. These are both practical difficulties (such as funding being restricted) and the distraction that comes with them. So what could have been a fairly straightforward case (every body was the same, and the killer was clearly from nearby) was like wading through mud to reach any kind of breakthrough.

In a film, that’s a problem: most of the film is slow and studied, with the two priests feeling their way through an uncooperative system. Thus it is interesting, rather than exciting, until that breakthrough arrives. I’ve seen the book described as “harrowing”, but apart from brief but graphic views of the dead boys, that word does not apply here at all. There are a few moments of tension when the slow investigation is broken up with visits to the killer’s mind, but there is little that feels really gripping until Saenz and Lucero are closing in on their target.

(And still, humanity is applied to the story, sympathy granted even to the antagonist’s background. By the priests, that is, not the police or law.)

The acting in Smaller and Smaller Circles is excellent throughout. Unusually, I cannot pick out an example that is better than the others: the two priests are utterly natural, the politicians appear to be real politicians, the police and church authorities come across almost like wannabe gangsters… But even that feels believable, due to both the acting and writing.

The film was written and produced by Moira Lang and Ria Limjap, and I consider it a great benefit that both were carried out by the same people. They adapted a hefty and well-known novel for a script that was just under two hours long, and they used sets that were perfect for both the story and the sense of place. Scrap heaps, mobile health clinics, opera houses, and laboratories: all were sharply realized. Apparently, the filming took twenty days, all told, though it was incredibly well done. None of it was over-fussy or pretentious; though there are a few of these grand, precise shots, standing out as if to put everything else in perspective.

Smaller and Smaller Circles was directed by Raya Martin, and he did an excellent job in setting up the various components to both the mystery and the prejudices the priests had to deal with. (Interestingly, very little they encountered had anything to do with religion.) It’s just a pity Martin couldn’t make the plot move along at a better pace. I guess in Hollywood, that might have been done with dramatic music (I found myself remembering the library scenes of Seven at times); but as it was, the style did reflect the sense of going nowhere slowly that the two priests probably felt.

And the real strength of the film was in the partnership between Saenz and Lucero. Sometimes it was like student and teacher, but other times the younger Lucero has to play a calming influence to Saenz’ frustration. They also worked well together and were friends (strictly after work) bringing to mind early True Detective (Rust Cohle gave me my opening quotation).

Considering how much time has passed since the novels first release, the author F.H. Batacan was asked if that would affect the relevance of the film. But no:

“The country’s poor are still disposable, expendable, and trapped in a broken system with very little chance of advancing in life. And the powerful, regardless of their political color are still blithely uncaring, defiantly incompetent, or spectacularly corrupt—if not, then some virulent combination of all three.”

Yes, I’m sure it’s all still relevant; perhaps even more so when you consider that this isn’t a film set in the slums, but amongst educated people looking at those who live in slums. I don’t believe IMDb even credited the child actors who became victims.