The long history of cinema has given us directors we imbue with a sense of reverence, whose names we utter with hushed tones, whose films we analyze with keen eyes. Steven Spielberg, Wes Anderson, Christopher Nolan, Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, Woody Allan, Spike Lee — each have distinct styles and intention behind their filmmaking, contributing significantly to cinema.

But Quentin Tarantino stands apart. We neither whisper his name nor merely analyze his films — we pore over them for minuscule homages to the deepest, most obscure cinema, for momentary, flippant, yet purposeful in-jokes and self-references. He’s steeped in film lore; he speaks cinema, both the elevated and the base, the jargon and the slang.

Quentin Tarantino is a singular director. As fellow RSC critic, M.N. Miller said in his review of Once Upon a Time In Hollywood:

“there is nothing like a Quentin Tarantino film. Nothing. There are few film experiences during which you can instantly know you are watching the former video store clerk’s unique blend of style and dialogue, yet each of his nine films has been singularly different from one another.”

His filmography seems like no other. It’s a series of purposeful steps; intentional choices inform what he makes. Now, other filmmakers have done the same thing, lining up funding for a dream project like Christopher Nolan making the Dark Knight Trilogy so that he could eventually make Inception.

But Quentin Tarantino is a different breed altogether. His movies are precisely his. No one could rip them off. From his unique dialogue (similar to Kevin Smith, but still bearing his own vernacular) to extra-gory scenes, to Hollywood homages, to his own cast of players, to mind-blowing shocker endings, nothing else is like a Tarantino film. And yet they’re all different from one another.

Tarantino started out as a video store clerk who wanted to make movies instead of renting them. He grew up steeped in film and music culture, letting it not only wash over him but soak into him. It practically oozes from his pores. He’s said he’ll make ten films and then retire, rather than making a string of flops as he tumbles into obscurity and old age. He’s made nine so far. He wants to cultivate a filmography rather than just be a director for hire. He wants to focus on writing film criticisms and novels and programming the films shown at his theater, The New Beverly, in Hollywood.

I’m going to rank Quentin Tarantino’s nine-film filmography here, but I’ll preface by saying that this isn’t like other rankings; he makes excellent movies. Moreover, they’re all unique — there’s really a built-in problem with the premise of ranking them. Basically, after the bottom two, I can easily say that probably depending on how recently I’ve watched them, each one could rise to the top of a ranking.

But those are our wonderful, maddening, self-imposed restrictions, and I will abide by them!

To that end, I rewatched Tarantino’s filmography (and saw Once Upon a Time in Hollywood twice) to keep them all fresh in my mind.

My rules: I’m counting Kill Bill as one movie, even though it’s two volumes — Mr. Tarantino does it, so that’s good enough for me! Also, I’m only counting his “Written and Directed by” films here, so no True Romance, From Dusk Till Dawn, Natural Born Killers, Crimson Tide, or The Rock (he wrote those first three, and the last two he did uncredited rewrites on).

9. Jackie Brown (1997)

Jackie Brown is probably Quentin Tarantino’s most conventional film, which makes it seriously unconventional for him. He had to follow up the cult classic first film, Reservoir Dogs and his gonzo smash hit Pulp Fiction with something, and he chose to really dig deep and make a pensive movie.

Pam Grier and Robert Forster, both of whom were critically lauded for their performances (Forster garnering an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor) are absolutely pitch-perfect in their roles. Jackie Brown (Grier) is a flight attendant who hopes to double-cross the man she’s been smuggling money for (Samuel L. Jackson).

It’s a solid crime switcheroo. However, it’s missing Tarantino’s feeling, his signature wit seems grafted into another story—which it is. Jackie Brown is based upon a novel by Elmore Leonard. It’s his only adaptation, and the story is told chronologically (mostly — we’re still talking Tarantino, here), and there’s a lot less of his boisterous bonkers-ness.

That being said, it’s incredibly well-made and is a source he references often in later films like Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. However, it’s about half an hour too long and doesn’t quite move fast enough to make us forget the runtime, unlike most of his other films.

8. Death Proof (2007)

Kurt Russell plays the villain of Death Proof, Stunt Man Mike, who drives a death-proofed car. Of course, he uses that car to hunt and terrorize helpless women along the darkened rural American highways–that is until he meets a group of women who won’t allow themselves to be stalked or terrorized (Rosario Dawson, Zoe Bell, Tracie Thoms).

Death Proof was released along with Planet Terror (directed by Tarantino’s longtime friend and collaborator Robert Rodriguez) under the Grindhouse title, a broad homage to 70s exploitation horror films.

While not as high brow or as well-constructed as his other films, Death Proof remains layered with as many–if not more–film references as any. It’s really fun and filled with a whole lot of crazy. Death Proof‘s first half looks just like a 70s B-level horror film, complete with fake film grain and bad editing.

Then, it transitions into some higher quality, along with some of Tarantino’s stylizations: shifting into black and white, crazy music cues, etc. This is great cinema here — like I said before (and I’ll say again), Tarantino speaks fluent film.

Every moment in Death Proof feels imbued with pulpy, grody Hollywood history, and it’s just completely fun. And yet it adds to the conversation and modernizes the tropes a bit: this is a slasher film in which the women go on the offensive. They don’t wait until the last minute to finally beat the villain, but they go after him for the last act. It’s cathartic and brilliant!

7. Django Unchained (2012)

I’m going to reiterate my disclaimer: starting at this point in the list, each and every one of the films could rise to the top of Tarantino’s best.

Django Unchained is complex, brutal, emotional, hilarious, and beautiful. Following his diabolically charismatic performance in Inglorious Basterds, Christoph Waltz plays chaotic good Dr. King Schultz, a bounty hunter who frees a slave named Django (Jamie Foxx) in order to track down some horribly abusive slavers.

What ensues is a revisionist spaghetti western revenge fantasy, with Django and Schultz trying to find Django’s wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) so they can rescue her from one of the most despicable characters ever depicted on screen: slave-owner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio).

Django Unchained earned five Oscar nominations: Best Picture, Cinematography, Original Screenplay, Sound Editing, and Supporting Actor–Christoph Waltz won for Supporting Actor and Tarantino won his second Original Screenplay Oscar (his first came for Pulp Fiction).

It’s a difficult movie to watch, with frank, excruciating depictions of slavery, accompanied by accordingly explicit language. While Tarantino has absolutely deserved criticism for his use of racial expletives in his previous movies (particularly in Jackie Brown and Pulp Fiction), the context here adds another layer to the already visceral impact of slavery. It’s a movie that, in many ways, needs to be seen to make sure that no one forgets the evils of our past, but that is also off-putting for the casual viewer. But that’s the point, isn’t it?

6. The Hateful Eight (2015)

I saw The Hateful Eight with a bunch of friends from work. When we walked out, we all started discussing our reactions to this intense, bloody film. One of my friends observed that she thought it was beautiful, really well-made, and super suspenseful, but she really just didn’t like it. She told us, “I just really didn’t like the characters! They’re all terrible people.” She had a point–they’re all horrible people. I replied, “Yeah, that’s why they’re the hateful eight! Not the warm and cuddly eight! It’s in the title!”

That’s the point of the film: this is a (nearly) one-locked-room whodunit set in the middle of a blizzard in 1877 Wyoming. Samuel L. Jackson stars as Major Marquis Warren who hitches a ride with bounty hunter John “The Hangman” Ruth (Kurt Russell) who’s transporting the evil Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh) to Red Rock to hang for her crimes.

A blizzard traps them inside a cabin with a truly hateful cast of characters. They meet a horrifically racist Confederate general (Bruce Dern), a former Confederate-turned-sheriff (Walton Goggins), and a bunch of gang members (Tim Roth, Michael Madsen, Demián Bichir, and Channing Tatum). Everyone has some sort of lie. Someone is betraying and plotting to kill the others, and everyone is a suspect.

This is my kind of movie: a bunch of characters stuck in one place, talking and arguing. From a construction standpoint, it’s a nearly perfect film. The cinematography is perfect, as is Ennio Morricone’s haunting score (for which he won an Oscar). The writing, as expected, is razor-sharp. This should probably be my favorite of Tarantino’s films. There are some majorly problematic things: the violence toward the women and increased use of racial slurs knock it down a few pegs for me, as they’re not aging well (and shouldn’t).

5. Pulp Fiction (1994)

Pulp Fiction Poster

This might be the one that I catch the most flak for bumping down on my list. Remember, catch me right after I watch it and I might argue for it to be number one. Following Reservoir Dogs, Tarantino seemed to be settling into a pattern. He was the gangster-crime movie guy, the non-chronological narrative director. He tells a series of interconnected, fractured stories about criminals in LA. It’s really a series of long scenes of dialogue and diatribes, of mishaps and mayhem put on by these criminals and the people they encounter.

There’s no star, really, though you can make the argument for Samuel L. Jackson’s Jules and John Travolta’s Vincent, as they’re sort of the thread that connects everything.

It’s the movie of the 90s for many people. You couldn’t go into a dorm room or bachelor pad for the next ten to fifteen years without a Pulp Fiction poster on your wall. No costume party went on without a Mia Wallace/Vincent Vega (Uma Thurman/John Travolta) impersonator or four.

Everyone quoted Samuel L. Jackson as Jules misquoting Scripture before killing the yuppies. Every high school and college student wore out the soundtrack (I had it on CD and cassette before I’d even seen the movie!). It’s infused with homages and references to anything and everything Hollywood, and it made me want to learn more about film.

I think it’s nearly perfect, with a few major flaws: Tarantino’s use of the n-word for no purpose other than to have it, and its overall point. While I’m fully aware of its place in postmodern cinema: there’s not really supposed to be a point. And that’s fine. I can still enjoy the film. But because (most of) Quentin Tarantino’s later movies are truly trying to say something meaningful, I have to give points to those.

4. Inglorious Basterds (2009)

Quentin Tarantino worked on Inglorious Basterds on and off for over a decade, shelving the script and then dusting it off and coming at it again. It stars Brad Pitt as Aldo Raine, an American lieutenant in charge of a special forces unit (called The Inglorious Basterds) with orders to terrorize and scalp Nazis behind enemy lines.

Meanwhile, SS Officer Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz–winning his first Oscar for a Tarantino movie for Supporting Actor) is on a mission to root out all the Jews in Nazi-occupied France. These storylines converge as the Nazi brass, including Hitler, attends a major propaganda film premiere in Paris, and both the underground resistance and the Basterds intend to blow up the theater and end the war.

This represents a major leap forward for Tarantino’s directorial style, just as Kill Bill did. It’s a polished, beautiful film, an homage to World War II epics like The Dirty Dozen and The Guns of Navarone, while also demonstrating a phenomenal grasp of complexity and nuance and suspense.

There are many, many long scenes of conversations (already a Tarantino trademark), but rather than filling those conversations with offshoots and non-sequiturs into the annals of pop culture, Tarantino relishes in the suspense of the situations, not letting the audience breathe for wondering the outcome.

A few of those scenes just don’t work as well as in other films–like the opening scene in Reservoir Dogs or the entirety of The Hateful Eight. However, as Aldo says to “Little Man” (BJ Novak), Inglorious Basterds “just might be [Tarantino’s] masterpiece.” I disagree slightly, as you’ll see in this Ranking–but I don’t want to spoil things for you.

3. Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Quentin Tarantino’s debut, Reservoir Dogs, presents a nonlinear narrative about the planning for and the fallout from a diamond heist. It’s fast-paced and pensive and brutal. It establishes what would be many of Tarantino’s hallmark moves: an ensemble cast, long scenes of dialogue, often about nothing important other than characterization, pop culture, and mood. It’s soaked in blood and loud, unflinching from the dark reality of the world, but still with a light touch.

It’s hard to critique this one. It’s so very solid. While his other films tend toward the sprawling epic, Reservoir Dogs is tight and taut. There’s nearly no fat here, with Tarantino bending everything toward characterization and tension. Its opening scene has oft been imitated but never matched for its ability to flesh out characters and drop us into a story while also feeling incredibly real. It’s an excellent, brilliant film on just about every level.

2. Kill Bill, Vols. 1 & 2 (2003 & 2004)

Poster image of Kill Bill

This whole bloody affair follows The Bride, a character conceived of by Tarantino and Uma Thurman (credited as Q & U). The Deadly Viper Assassination Squad (Vivica A. Fox, Lucy Liu, Daryl Hannah, and Michael Madsen), led by Bill (David Carradine) attempted to assassinate the Bride on her wedding day, but only succeed in killing her entire wedding party and putting her in a coma for four years. And so, she must have her revenge.

This is a bonkers film, conceived of and shot as a single film, but split up because of its nearly four-hour runtime. One by one, Thurman’s Bride hunts down and takes her revenge on the people who destroyed her life, each one with a bloody, violent, beautiful set-piece. As she gets closer to Bill, the fights get more difficult and brutal–and more personal. Kill Bill is modeled after martial arts, samurai, spaghetti westerns, and blaxploitation films.

For the longest time, I said that Kill Bill, Vol. 1 is the best Quentin Tarantino movie. It’s the most fun, the most action-packed, possibly the best acted by Uma Thurman. That might remain the case. However, the only reason Kill Bill (as a whole) doesn’t hold that number one spot on this list is because Volume 2 is just nowhere near as good. It’s not in the same ballpark. In fact, if I wasn’t combining them into one film for this review, Volume 2 would be dead last. Don’t get me wrong, it has its moments: the coffin escape, the Ellie Driver fight, and the opening monologue are brilliant. And don’t forget, this is a Quentin Tarantino flick: it’s inherently great, just not up to par with the rest.

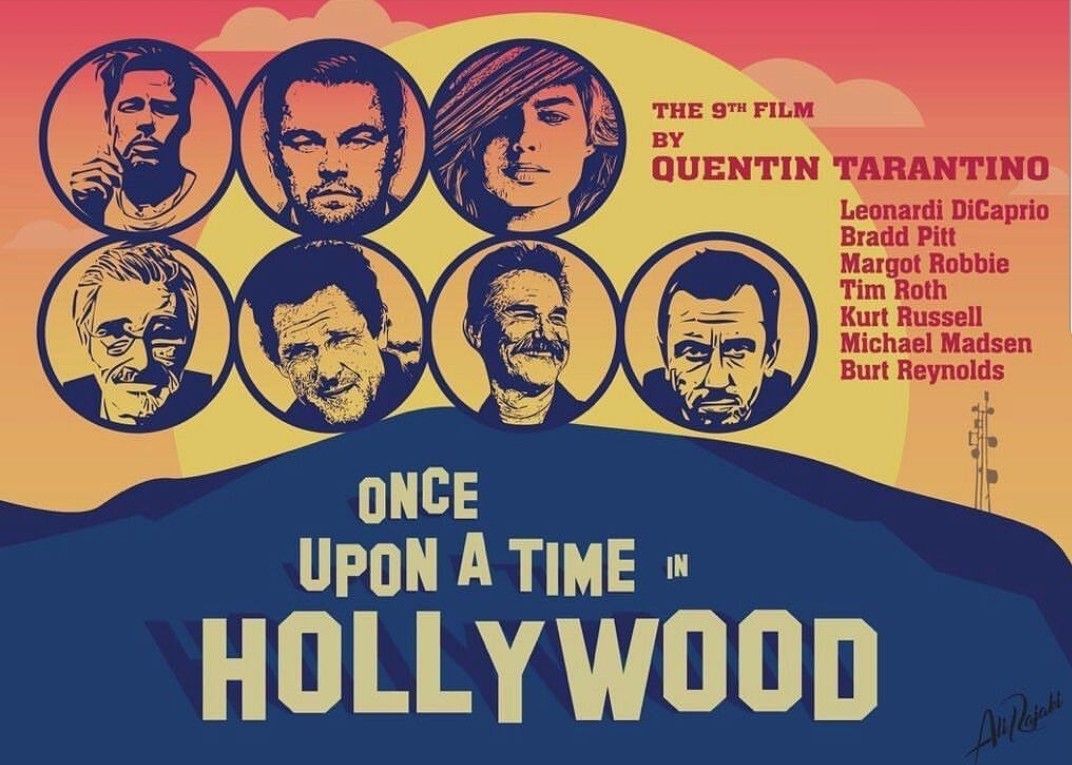

1. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

Poster for ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’

According to Tarantino’s longstanding (though oft-disbelieved) claim, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood will be his penultimate film. I say, regardless, it’s his magnum opus.

Leonardo DiCaprio plays Rick Dalton, a waning Hollywood star in 1969, and Brad Pitt plays Cliff Booth, Rick’s stunt double. The two men are inseparable, Dalton desperately trying to hold onto his stalled career while Booth is sort of aimlessly continuing on as his friend’s gopher. They stand on the cusp of middle age at the same time that Hollywood’s golden age is fading, and both men need to figure out how to navigate the rapidly changing world.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is easily Quentin Tarantino’s most lovingly made, precisely crafted film. It’s a heartfelt love letter to Hollywood, creating a true sense of time and place and life. This has always been Tarantino’s strong suit, which he’s developed and honed since he began: creating a sense of character and place.

The layers of reference and homage are deep, and Tarantino’s matured, deft hand is felt—maybe for the first time in his career. Instead of simply having characters reference films or music, we live it with them. He lets us fall headlong into 1960s Hollywood in all its glory and foibles.

It’s a thoroughly engrossing, deeply layered film about a transition in life and time. The backdrop of the Manson murders, against which Tarantino has set Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, symbolizes this nearly violent change of times. The times are truly changing, and the hippies are going to try to kill off the old guard–but they won’t go quietly.

Gone are films like The Great Escape in favor of Easy Rider and exploitation films. Tarantino has no major problem with those films; they’ve been his vernacular since he began making movies. He simply adores this bygone time and laments its waning presence today. It’s beautiful and haunting and meaningful—easily Tarantino’s most restrained, impressively constructed film.

At this point in Quentin Tarantino’s career, I honestly think that he should wait to make his final film (if indeed he only has ten in him). I think he should wait until, like Clint Eastwood, he’s gotten beyond his Dirty Harry years and makes a film about old age. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood seems to me like his true pièce de résistance. He should let it sit with us for a decade before dropping his last film.

But I won’t complain if he scrubs his self-imposed limit and keeps giving us more.