Summary

Gentle, but thought-provoking drama about a young professor taking a wrong step in class, and about his family trying to step around the decline of their beloved grandmother.

Having watched and enjoyed Echo Boomers recently, a crime story with a theme of generational conflict, it was especially interesting to find myself watching another film with a similar theme. Safe Spaces (or After Class, as it was called in the USA) isn’t about resentment towards career success though, but rather different expectations that Generation Y and Millennials may have towards communication and honesty.

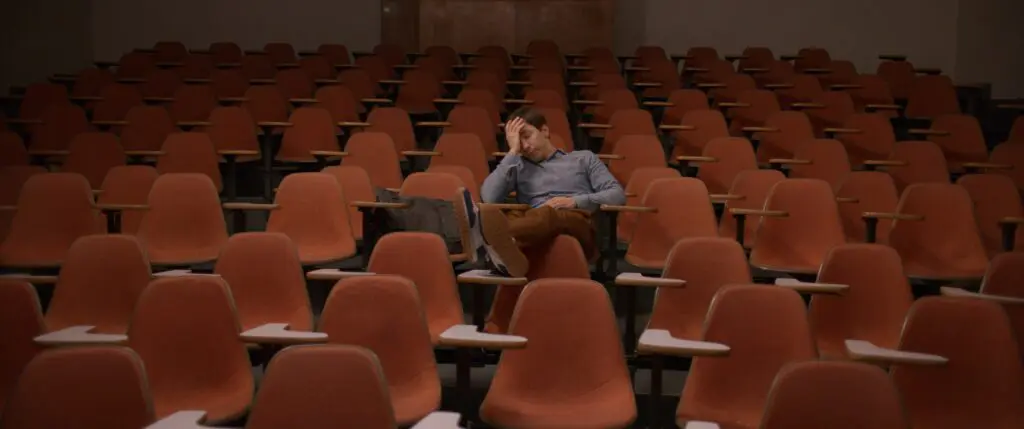

Safe Spaces follows Josh Cohn (Justin Long) navigating two crises in parallel; one in his career and one in his family. He has little control over either (for different reasons) but somehow manages to clumsily make matters worse for other people in both. This may sound like a comedy (and the publicity told me to expect a “dramedy”), but it certainly doesn’t feel like it while watching: it feels instead like writer/director Daniel Schechter has produced a case study of modern city life as a white man.

Justin Long – though still doing cartoon voice acting – has certainly grown up in his roles, as The Wave and Giri/Haji demonstrated last year. There’s no doubt his character is baffled by what life wants from him (a feeling Long seems to have been born to present), but when the whirlwind settles down and he can think clearly again, Josh finds he can actually see everyone’s point of view. So now what?

I’m referring to the main character by his first name for a change because as it happens in this film, about half the people who appear have the same last name. His beloved grandmother Agatha (the late Lynn Cohen) is in hospital, barely taking a breath after one ailment before being floored by another. The richly drawn New York Jewish family, including Josh’s parents (Richard Schiff and Fran Drescher), and siblings (Kate Berlant and Michael Godere), as well as various spouses and offspring, all have their own issues and strikingly different ways of responding to Agatha’s condition. Here lies the crisis in the midst of Josh’s family, and a little more time is spent with these people than those he mixes with at work, a city college, where he teaches creative writing.

In his class, he encourages (or pressures) his students to be honest: “Embarrass yourself. Write what hurts.” This may be a valuable philosophy for writing, but it is most definitely not what these young people want in a classroom setting: they want consideration and compassion. In contrast, there does seem to be a place for honesty in the family, when people can manage it. There is definitely a great deal to observe and think about here in relation to how we might respond to different people and situations, and Safe Spaces does not take sides, present an answer, or preach. It does, however, poke fun a little at those who do preach and makes it pretty clear that one has to speak with care in order to be listened to and supported.

So yes, there may be some very mild satire here in Safe Spaces. For the most part, though, the message about sensitivity towards others comes with one of perspective: you cannot tell what individuals you meet (or teach) are going through, but there are good odds that their lives aren’t as rough as the Jews who survived concentration camps, as the central grandmother did. Some have likened the film to a mild Woody Allen comedy, but there’s no self-deprecating sarcasm in Safe Spaces, but warmth and introspection.

The film sees both crises to their conclusions but does not provide a conclusion in itself. This somewhat ambiguous ending – especially in relation to Josh’s character development – is perfectly appropriate in my opinion: life is not clear cut. Not every criticism towards something a black person says is due to racism, just as not everyone can talk openly about delicate subjects. Safe Spaces boasts a cleverly and wittily written screenplay, and I hope it will be viewed widely and generate many conversations.