Summary

Natalie Palamides: Nate – A One Man Show isn’t as funny or clever as it thinks it is, but its so-called examination of consent will at least compel you to say no in pretty clear terms.

Natalie Palamides: Nate — A One Man Show was released on Netflix on December 1, 2020.

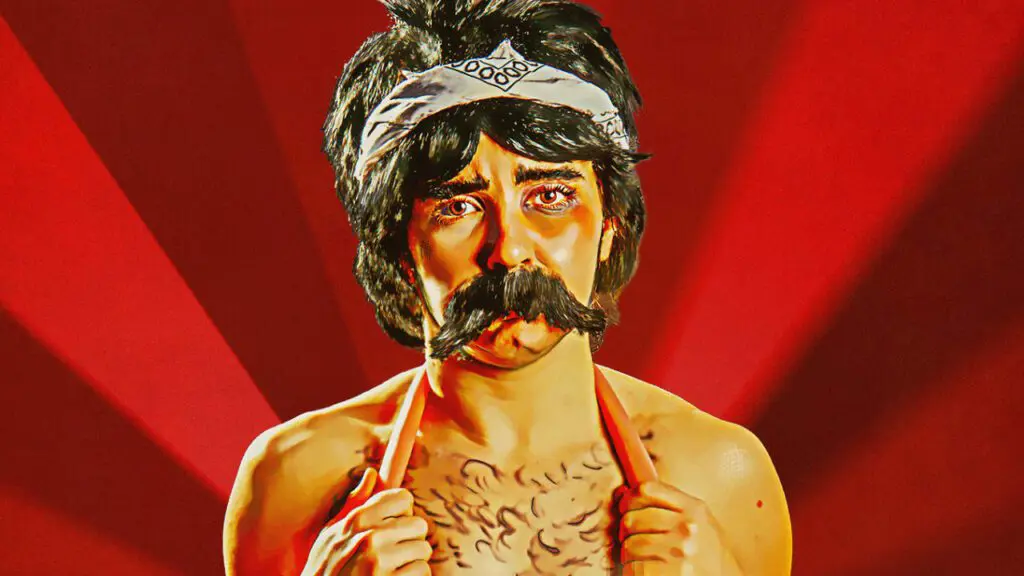

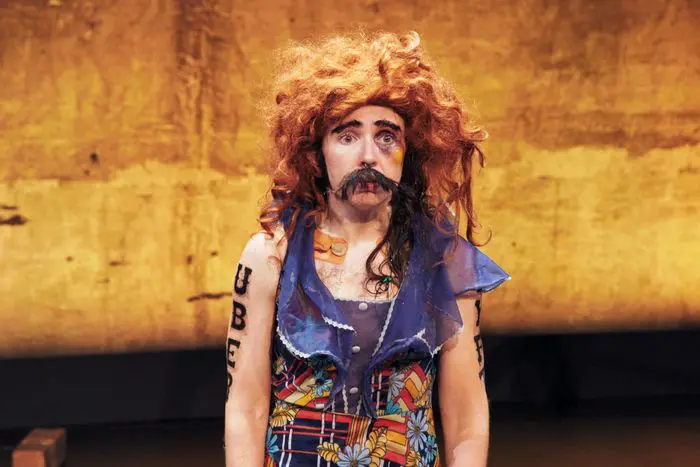

Nate is a man. And not just any man, you understand, but a cartoonishly exaggerated stereotypical manly man, with bushy sideburns, a mustache halfway between Borat’s and Wilford Brimley’s, and bristling stuck-on chest hair beneath an open fleece-lined jacket. He wears comically oversized camouflage pants and rides on-stage through a smoky haze of pyrotechnics on a comically undersized motorcycle. Part of his opening gambit is to gobble a scoopful of protein powder, which he promptly spits out in a brief arc of flame, choking and spluttering on the remainder. The rest of this supposedly one-man show, which nonetheless relies heavily on the befuddled audience, a mannequin, and several other props, plays very much like a performer determinedly hacking up the claggy remnants of something designed for one purpose and put to misguided use in another.

Nate is also Natalie Palamides. Nate, the show, is another of those proudly experimental stand-up specials which seem as determined to redefine the boundaries of the form as they do to not be funny in the slightest. But whereas something like, say, Nanette at least has a cogent point and a distinct authorial voice, Nate has a surface-level pastiche and an inflated sense of self-importance. In a prologue during which Netflix braces us with audience testimony and comments from producer Amy Poehler insisting that the show elicits genuine confusion and anger, we’re told that “that’s art, baby.” But is it, really?

I suppose, in a sense, it is, but in that same sense so are the things engraved on toilet cubicle walls, and those are much less pretentious. We’re to assume, because Nate is gradually threading a narrative through its patchwork assemblage of performance, audience interaction, and explication, and because it’s touching on serious and difficult to answer questions, that it’s a work of ambiguity and nuance. But there is very little nuance in leading an audience through a chanted reminder to just ask permission before groping someone’s genitals – anyone grotesque enough to not have known that ahead of time isn’t likely to be suddenly swayed to feminism at this point, and nobody in their right mind would consider it an ambiguous issue in the first place.

What Nate believes to be its cleverest meta flourish is also the source of its most crippling awkwardness and stop-start pace. Often, Nate will address the audience directly, not just to make fun of them, as most comics do, but to rope them into the performance as characters in the story. During one section a man is brought on-stage for a topless wrestling match, and he’s into it enough that, if you squint, you can sort of see the logic behind Palamides using the audience to construct the show’s story. But later, when Nate repeatedly yells, “Hey, Lucas!” into the crowd, waiting for a willing response, the amount of time that has to elapse before someone gets it is unbearable. The dude who eventually answers the call lollops onto the stage on a couple of occasions to play Nate’s best friend and looks decidedly uncomfortable each time. This unease and awkwardness is not a commentary on consent, but the painfully obvious anxiety of non-performers being led through a not particularly well-constructed routine.

Nate – A One Man Show wants to live in the surreal space between dumb immaturity and a genuine interrogation of tricky themes and ideas, but it’s too underwritten to work as the latter, and any point it has to make beyond the obvious ones is obscured behind the bushy mustaches and rubbery penis props. Any laughs the show is able to summon are accidental cackles of awkwardness when the dead air between beats becomes suffocating. The only genuine insight to be gleaned doesn’t pertain to consent or performance or gender, but to how unwise it is to make this light of such heavy topics. The show ends with Nate once again asking a question of the audience, inquiring about whether what they’d just seen was acceptable or not. Everyone in attendance is too confused to give an answer one way or the other. I knew how they felt.

Thanks for reading our review of Natalie Palamides: Nate — A One Man Show.