Larry Fessenden has been making films for – let’s say – a number of decades, a thoroughly hands-on auteur in the American indie horror scene. An interest in such films had crept up on me over about half that time, so I was most intrigued to find out what insights he had to share. His latest film, Depraved, has recently arrived on Shudder, so we talked about that, as well as his approach to films, his production company Glass Eye, and a little philosophy of life.

I introduced myself as having been writing for Ready Steady Cut for just over three years, relatively new to interviewing, and laughed that Larry must have been talking to strangers about his films for much longer. (“Go easy on me,” I begged without saying it.) “Yeah well it’s fun to connect with people,” Larry said “and find that people do watch the movies, after all the work. So it’s fun!” And presumably, you make those movies as much for the fun, as for the audiences? “I take it all quite seriously: the idea of communicating, trying to find commonality with other people through movies, even if they’re scary movies.”

The name of Larry Fessenden is very well known in the indie horror industry, but not so much outside of it; he seems to be a legend in his own field. So I asked Larry how he sees himself. “I loved Jaws when I was little, so I thought I would be a filmmaker like that. But at the same time, in my generation, I didn’t really know how to ‘break into showbiz’, so my point is you have different levels of ambition, and as you get older, you realize there are many different careers. I also very much like George Romero, he is a role model, and he always felt frustrated that he wasn’t supported by Hollywood; he had a few forays. At some point they attached the word ‘icon’ in front of my name, and it’s a complete mystery but why wouldn’t I take it? Not for the ego: I always say you want good reviews, and words like ‘icon’ in order to gain power in the industry to make good work, or support other people’s work. That’s really the agenda. So it hasn’t worked out terribly well, but it’s still nice to have a voice; in that, I’m privileged. Even in my small section of the world.”

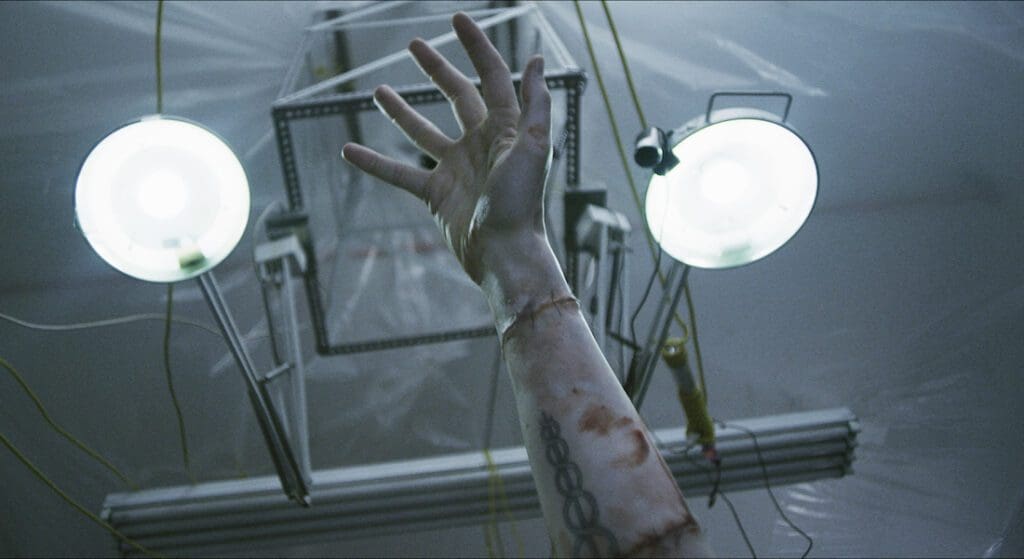

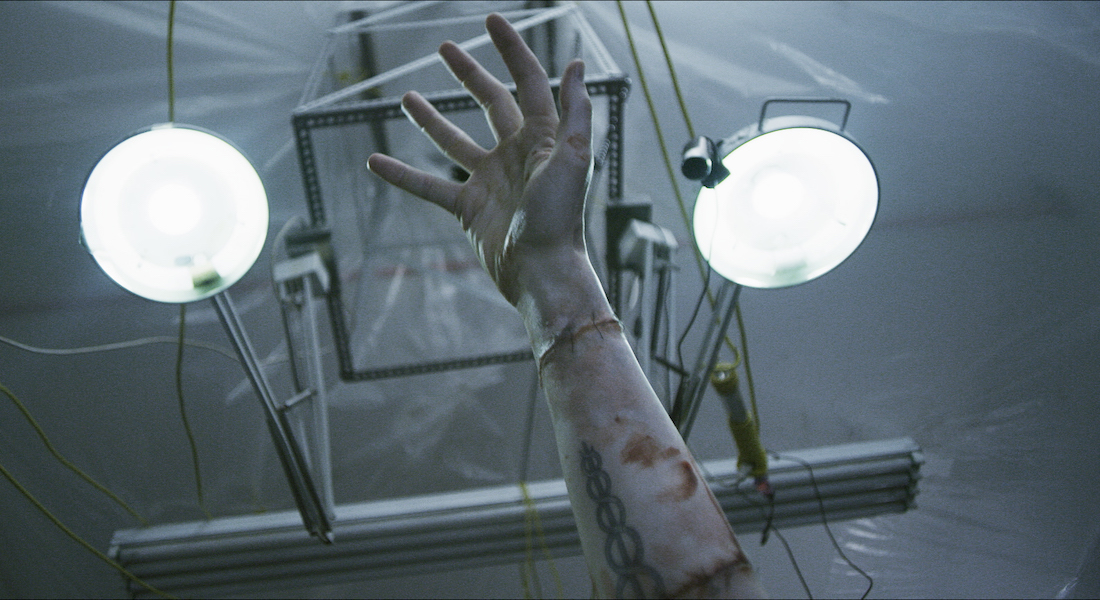

Depraved was written, directed, edited, and produced by Larry Fessenden; an impressive range of roles just in one project, though it does reflect somewhat his whole career. It was a captivating film, and I found myself most interested in some aspects of the writing. Depraved is an adaptation of the Frankenstein story, largely from the monster’s point of view, and it opens with a scene that shows where his brain was obtained from. I asked how a writer decides where to start a story: this one could have started with the doctor’s research, with his inspiration for it, or indeed at almost any point. “Absolutely,” said Larry. “And I think what struck me was that that in the overhashed story of Frankenstein what hadn’t been explored was the experience of the monster. So with that in mind, I wanted to portray a very personal thing, which is that life is bewildering and alienating and you always feel unsure of your place. I think that’s very universal, no matter where you are. This takes me back to what we were saying about career: I love that Scorsese never knew if he was going to be able to make another movie, all through the seventies and eighties, yet he is now one of our most cherished filmmakers. So you have to always know that no matter where you are in the pecking order, there is still insecurity and no sense that anything is definite. I wanted to bring that personal subjectivity to the story of Frankenstein’s monster, and have him wake up, be an individual who doesn’t know his past, doesn’t know who his friends are, and has to learn life all over again. So that’s what led me to have the opening scene, and from there just traced a very familiar story through that lens. Many stories would start with the doctor, the lab, and everything; but I do show the creation of the monster, through his own eyes, when he discovers the videos. So this is just a way to re-engage and revitalize the true pathos of the story: he doesn’t know how he came to be. And I think that’s a strength that films have: to surprise and reimagine a story through pacing and how you reveal the story.”

I asked Larry whether he’d stretched his creativity like this before, writing from the point of view of a completely fictitious creature. “Well, I made a movie called Habit, which is about a guy who lives on the Lower East Side, drinks too much, meets a girl, and becomes convinced she’s a vampire. So there I’m asking again a fundamental question: in taking these great stories – the vampire, the Frankenstein monster – and let’s picture what it might really have been like. That’s the question I ask. If I’m going to do a home invasion or a slasher, rather than using the tropes of horror to create a wonderful artifice, I’d rather consider what it would be like from moment to moment. That’s sort of my way into any story. If I made a war movie, I wouldn’t be concerned with the great battles, but the things you carry in your rucksack, what takes you to the next moment. So it’s just a matter of scale: my vision of life is about the details and how profound they are. My movie is called Depraved, a rather lofty word which kind of invokes butchery and people frothing at the mouth; but I’d rather listen to that word again and look at the little depravities in the way people act with each other. So it’s trying to get you to focus more on the so-called daily horrors of life.

Something else interesting that struck me about Depraved was the trauma the doctor had experienced as a medic in Iraq, and how he was in firm denial of it. “I’ll answer your other question first, about getting into his shoes, thinking about the monster’s brain. I learned a bit about the brain from a book called ‘My Stroke of Insight’, about Jill Bolte Taylor who had a stroke, and she happened to be a brain doctor. So as it was happening, she was very self-aware, saw the abyss, and was slowly brought back. She reconnected her synapses and is now functioning, wrote a TED talk, but there’s a part of her brain that’s gone. I highly recommend the book and the talk, in which she talks all about her experiences. That was influential in terms of the monster, how he tries to remember his former life, reignite cognition.

“As for the doctor, I read another book called ‘On Call in Hell’ and that was an account of being a field surgeon in Iraq. You could see the sense of loss that this doctor had and the passion to save lives at all cost. I felt that was a story we don’t tell enough, especially as I read the book during the Bush era when we were in Iraq: there was all this political talk, but nothing about real experiences of doctors who wanted to save the kids. Once again it is about thinking more closely about personal experience on the world stage, or in the genre of horror.”

Thinking of other characters in Depraved, I asked is it just me, or are the most likable characters the women? “Of course they are,” said Larry with a big smile. I especially liked Shelley (who the monster – called Adam by then – meets in a bar) and asked whether she was based on someone Larry knows. “Maybe, in the sense that she’s the one I’m most fond of, she’s like the kind of chick I’d hang out with in a bar. A salt-of-the-Earth character, but it’s also Addison: she brings such humanity to the character. She’s a loner and a bit of a drinker too, she’s at this bar, and willing to talk to this slightly creepy fellow and give him the benefit of the doubt; which, you know, leads to tragedy. It’s an observation about how sad the world is: two people who cannot connect. I always joke that I make feminist films because I feel the male ego has driven history and driven it into the ground. As I’m an environmentalist, thinking about the imagery of mother Earth and all those things, I always feel it’s the childish male ego that’s responsible for so much damage in the world. Look at the male characters: there’s rivalry like two boys in a sandbox. And now we have an entire national drama in America based on these kinds of emotions, all of which I think are entirely disdainful. The other thing is that in most horror movies the women get killed, and there’s an unfortunate feeling of glee from the filmmakers creating this exploitation feel. Not that I’m above anything, but my interest is to show how innocence, kindness, and tenderness are the first casualties in this society we’ve built. So that’s really what the girlfriend, Elizabeth, represents: even the monster knows this, but he acts on it not to hurt her, but to hurt the doctor, his ‘father’. Once again you see this sad chain of pettiness and desperation from the men, and the women fall by the wayside.”

Adam’s character had to grow up rapidly and didn’t have the chance to do so except with the influence of two significant male figures. “The film’s about, well, lots of things, but mostly fatherhood. Henry’s very sweet at the start, very patient, but he lets his own ego and disappointments and frustration and – quite honestly – his lack of interest get in the way. The monster is tender enough that he feels that psychological violence and rebels against it. So it’s also about those little shocks in life that lead to damaged people: in this case, the monster is clearly damaged and lashes out, which is just the same trajectory of the book: I didn’t make anything up here!”

There was something Larry had certainly added which I liked a lot: there were swirling colored graphics added that presumably reflected Adam’s mind developing, though I wasn’t sure how to interpret them. “Everything is for the audience to decide what it’s about. But I wanted to assert that the brain is how we interpret the world: the brain is actually a physical thing that is having synapses and little jolts. And it’s also a reference to the Hollywood versions of the story where the monster is brought to life with electricity. I don’t have that in my movie, but I’m saying that the brain is driven by electricity: that is in fact part of my Frankenstein story, in that the electrical impulses are our synapses, which are reconnected if you have a stroke. When I make a film, I like to get into that world and see the connection of the themes. I had some resistance to those effects, even from my collaborators who felt they were a bit goofy, but I felt we haven’t seen that. I’m always aware that my body is a part of my experience in how I’m seeing things, so I wanted a layer of that awareness on top of the movie. And only in the Frankenstein story do you have this as part of the DNA of the story, a reason to think about a person who has been reanimated: you wouldn’t see this perspective in any other story, so you have an excuse to contemplate those things. Well, maybe you could in a thriller or detective story: they have things on the screen in the Sherlock show, invoking his thought process. It may be a bit ballsy, but these are the kind of experiments I want to do in my work because no-one really cares what I do: I don’t have any executive! Perhaps I pay the price of obscurity.”

I suggested that his independence does bring freedom, a notion which brought me back to the ending of the film, which I really liked: Adam simply walking away to find himself and his new life. The way it was presented was reminiscent of The Incredible Hulk that I watched as a kid: at the end of each episode, Banner walked off, to his next episode. I asked whether Larry had another episode in mind for Adam. “I do actually. I wrote Depraved originally as a TV series. I don’t love that format, because it often feels like it could go on forever, but in the course of trying to raise the money, I had several meetings with HBO. They eventually felt that they had other Frankenstein projects – none of which I’ve seen, so I think perhaps it was a way to get rid of me! But I do have a wonderful way to continue the story of Adam, and I am amused to think about that challenge of what you would do with that character.”

Larry didn’t give away any of that potential story: “it’s so sad when you go back and read this interview five years from now and see that I’ve done nothing. But you know, when I was a kid, I used to watch The Mod Squad with my brother, and they always used to have a walk-away at the end of the episode. I think maybe it was a fun seventies TV trope.”

The conversation broadened to other aspects of Larry’s career. I had first come across his name as an actor in other people’s films, such as You’re Next and We Are Still Here. I asked whether he had ever been tempted to tap the director on the shoulder and say you don’t want to do it like that, do it like this instead? “No, I’m firstly in the service of the director. I really believe in empowering that single vision and everyone needs to work towards that vision. But of course, any director can get lost and be helped by a gentle prodding. For example, I brought my experience to a scene where there was going to be a bloody nose, and I said I think we should make sure to get all the material up to that point because once the blood starts, you don’t want to be changing shirts and washing things. So I don’t mind asserting myself in a practical respect. I’ll occasionally say things like we might just get the wide here and we can go in later, so I can get a little bossy: not because I know best, but if I think I can be helpful. You always need to be sensitive to what they’re after. I’ve felt that as a producer: the director is really able to hear their own thoughts and instincts and you want to support them and gently push them towards that.

“I’ve had the experience of working for my son. He’s now twenty years old, but he was sixteen when he made his first feature, and I was an actor, producer, and DP, but it was his movie. So it was a very interesting dynamic, the father and serving his vision at the same time.” I was going to ask what it was like seeing his son take the same direction and supporting him with that: “it was good. My wife is very practical so of course, we were both mindful that it’s a tough road. But there are many jobs in film that are rewarding, and you don’t have to be endlessly at the typewriter, conceiving of an entire world: you can be director of photography, many crew positons. I really love both the art form and the burden of collaboration, the real check you have to have on your ego: you want to give whatever’s possible, without being overbearing. This is a very engaging activity, a rich soup; and I hope my son does some things differently from me. He’s maybe not as stubborn.”

So does Larry have a regret or two? “No, I just don’t know how I could have done all this differently. I’ve always been a loner, so maybe you have to ask for help more, so you have more people invested in your future. I don’t have an agent or manager, never have, so need to be understanding of my own personality. I don’t believe in regrets, either. You just make your bed and sleep in it.”

And then get out of it the next day, I offered. “Well exactly! ‘Soldier on’ is the other metaphor.”

Considering all the types of films Larry had been involved with, different subgenres, and so on, I imagined there was a cupboard somewhere full of props and costumes: is that right? “Oh, it certainly is! I have a barn upstate with a giant twelve-foot fish, a water monster, all the guns from Stakeland, zombie apocalypse signs, and everything. Actually, the loft in Depraved: we built that whole space and then got it in a truck and brought it down from the barn. If you were a Glass Eye fanatic, you could look and see props from different movies as set dressings there.”

Moving the conversation into the present, I had to ask what this year had been like in Larry’s part of the film industry. “Well, there’s general anxiety about how we can go forward. It’s interesting when you lose the ability to dream, that can weigh on you: you think about a movie you want to make and then realize it could be pretty difficult. Having said that, I’ve always been a creative person, and my wife has too: we made a film in May, a short film with my son as DP, made in isolation that addressed COVID, and that was cathartic. I’ve made music, I’m writing a script, and we’ve had the thirty-fifth anniversary of my company, so I’ve made videos celebrating that. It’s about being myself, and at the same time doing work in a community that is defiantly original. So I really like celebrating what Glass Eye stands for, it’s not really just self-glorification.

“What I’m saying is I think I’m extremely lucky, artists and writers who like to think are extremely lucky: isolation isn’t as devastating as it could be. Elvis Costello makes me laugh: he says he always likes his own company because he was an only child. I had two brothers but I have that feeling that I’m always able to be creative and I’m very lucky for that.

“As for the overall. I’m devastated by the political shenanigans in my country: it’s a disgrace to the notion of civilization. And, not speaking with hyperbole, I think it’s a disgrace to everything that one aspires to. This is, to me, the great fever that’s taken over, not the pandemic, but this fever of resentment and simple solutions: life is very complex and I very much prefer the idea of working together and understanding different perspectives, therefore celebrating compromise. All this is thrown out the window because of an overarching narcissism in our society and our culture. I think it’s a disgrace that humanity is so self-involved that we’ve lost touch with the real things that matter, both between ourselves and in our relationship with our natural world, and our arrogance that we’re separate from it is our undoing: I hate to see it so clearly happening.

“All this is part of the pandemic’s problem: we made this insane choice of either the economy or health. That’s the original sin of this entire tragedy: it’s not one or the other, the two things can work together if you’re sensible. It’s not about listening to science, but listening to reason. Maybe you’ll encounter this film I made called No Telling; it’s about animal experimentation and vivisection. It’s another Frankenstein movie. I proposed in that movie that science is not the only framework in which to understand the world, there’s also a spiritual reality. That was in 1991, and I feel that we had the luxury to make that point, but now we have to reassert that science has so much to offer. I also resent that we can disparage science while using it: the arrogance is disconnected from the reality on which our society is based. You know we have these white supremacists called the Proud Boys, who are proud of western civilization, but they don’t understand that why western civilization is even worth celebrating is down to the work of people like Galileo who tried to work out what is going on. And they sit on the pinnacle of all that thinking, all that work, and they act like just being a white supremacist is all you need to solve the problems.”

I told Larry he sounded like someone who had been holding this back all day! “Well actually you’re right, that’s the problem with being isolated: I can’t yell and scream at my friends in the bars. So I’m yelling at you, forgive me.”

We talked briefly about the silver linings of technology, and how different people I’ve spoken to have had a range of perspectives on this year of the pandemic. “Oh I’m not anti-technology: I’m just calling for more humility in all regards. Through humility, comes grit and strength: it’s not about surrendering in any way.”

Larry is currently making a video of the puppet show that they put on as part of a Christmas party every year. “We can’t do the party, so we figured we’d do a Zoom puppet show, and have fun. We’re blessed with technology: you can’t complain about how you’re going to make low-budget movies when you can make one on your phone. The thing is to tell stories, to communicate, to be thoughtful and engaging: it’s a great time for the arts. Maybe not for corporate artists; I also lament movie theatres being gone, but they’ll come back. It’s ok that we have to think differently now.

“The whole point of 2020, people wringing their hands and saying this is what horror movies have been speaking about with great seriousness: zombie apocalypses and so on are a way to digest a reality that we have a fragile system called civilization that could unravel at any moment, and we must be vigilant in protecting it and working together to be a successful society. Monster movies show how easily that can fall apart. Now that it is falling apart, I feel like saying we kind of explained that to you before.

“There’s an issue of mine that you’ll see in The Last Winter, a film I’m proud of: it’s a movie that condemns civilization for ignoring climate change. You asked about regret: it’s one of my regrets that that movie hasn’t been championed and watched: it’s the most devastating issue. Even when we get past the pandemic, we have another incredibly difficult problem ahead that requires some belief in science, some co-operation, and some rejection of the capitalist model that has led us down this road. But there’s no way that’s going to happen if we can’t even agree when we get COVID.”

Larry’s reference to losing “the ability to dream” had stayed with me, and I took the conversation back to filmmaking by asking if there is one dream project that he hopes to do. “That’s what I’m doing next. I’m not waiting anymore for permission: I’m carrying on in the low-budget realm, as I encourage other filmmakers to do. Many have made good films, and then they graduate, move on. People like Ti West, Kelly Reichardt all started out under my model of just low-budget, grit, and rolling up your sleeves. I find that I didn’t really graduate for various reasons: I’m happy to stay in this realm because I like the hands-on approach. If I work on a big film, which I’ve done as an actor, I find it a little bit alienating, though of course, it’s thrilling. And so I’m content and I have several more stories to tell, one of which I’m writing: I’m literally waiting for COVID to give me permission. And then I’m producing something which might come even sooner.

“So I’m continuing on in this way: I don’t really imagine a path in which things change and I’m suddenly making a big film. I do have scripts for that too, some outside of the horror genre. I’ve had many stories I can imagine and I’ve had fun writing them, and that’s another way to address the creative itch. Guillermo del Toro says that a film’s natural state is not being made, and there’s some truth to that, so you have to take some solace in the imagination and the writing and you can picture the movie. In fact, once you’re making it, it’s a heart-breaking step to realize you can’t get exactly what you imagine. Then in the editing, there’s a rebirth, and hopefully, that’s something you love, but it’s often quite far from the first impulse.

“There’s a line I say on my set that some of the crews find frustrating. I say ‘it’s good enough: let’s move on.’ And they say ‘what do you mean, good enough?’ I see the full picture: good enough will get us where we want to go. Lower your expectations and you won’t be disappointed. Perfectionism is such a struggle for many people, though for some it works to push them forwards. Scorsese is an example where you can see the struggle, and you can celebrate with him the accomplishments. Even Hitchcock: sometimes his camera moves were so ambitious for the time that you can see the camera shake, but it’s still there because basically, he said I want to show you the idea I had which is more important than the perfect shot.”

These names led to a question about collaboration: although that doesn’t come easily to Larry, is there any other director he would like to work with? “I’ve been lucky to be in one of Scorsese’s movies, so I did experience being on set: one wonderful day on Bringing out the Dead. And I knew all the guys on set because they’d graduated from Glass Eye! Anyway, it wouldn’t be a collaboration, but I’d just love being on the set of someone I admire, whose films I know intimately, to get a good sense of how he works. I have a good deal of affection for a lot of filmmakers and their quirks: I think Kubrick is such a thrilling artist, limited on one hand and completely consummate on the other. Along with Hitchcock, these are my favorite people to have in my life, even though I don’t know them personally: I don’t need to, they give me so much joy. And then there’s someone like Spielberg: I can watch his films and see his process, see how he’s putting together each shot, and that’s thrilling. Then there’s people I know like Kelly Reichardt, I’m always excited by her work: she shares with me her process with most of her movies. Art is a beautiful thing to be cherished and not limited by the wrong conversations.”

He teasingly left that vague and open-ended; no surprise, having seen a few of Larry’s films.