Summary

It isn’t always the most even or consistent show, but Showtime’s The Man Who Fell to Earth asks some important questions, gives some difficult answers, and is bolstered by a terrific, virtuosic performance from Chiwetel Ejiofor.

This review of The Man Who Fell to Earth Season 1 is spoiler-free.

Jenny Lumet and Alex Kurtzman’s Showtime adaptation of The Man Who Fell to Earth, based on Walter Tevis’ 1963 science fiction novel of the same name, begins with Faraday (Chiwetel Ejiofor) addressing a room full of excitable fans. He’s well dressed and well-spoken, a billionaire playboy type, giving something halfway between a TED Talk and a product demonstration. He describes himself as an immigrant. At this point we don’t know that he means a literal alien, having fallen from outer space.

But that is indeed where Faraday – he takes the name from a disinterested cop’s name tag – comes from. His home planet, Anthea, is in a state of some disrepair, and he has been sent on a mission by a missing inventor named Thomas Newton (Bill Nighy) which involves saving both his own planet and Earth from the ravages of a ruined climate. Integral to this plan is Justin Falls (Naomie Harris), a disgraced expert in quantum fusion technology that might hold the key to human and Anthean salvation. Probably, anyway.

I’m being vague about the plot deliberately since it requires the details to be limited for the drama to work. This version of The Man Who Fell to Earth is reminiscent of countless other films and television shows right from the jump, most of which were probably already inspired by the original novel or the 1976 Nicolas Roeg adaptation starring David Bowie, but no matter how much you can see the specter of, say, Terminator in how Faraday crash-lands naked and immediately falls afoul of the locals (it’s the police in this case, though I can’t tell if the optics are intentional or not), it’s fundamentally, at least in the early going, about two very different people learning gradually how to understand and relate to one another.

Faraday is lost. He doesn’t understand Earth’s language or customs, so his attempts to explain to Justin why she’s important come out as either gobbledegook or insulting parroting of things he has overheard, which he often doesn’t understand the context of. Justin sees him as a stranger who’s perhaps drunk or simply out of his mind, but she gradually begins to pick up on moments of technical brilliance or realizes that Faraday has access to information he couldn’t possibly know. He begins to convince her of the truth in what he’s saying; of, in a roundabout way, her own importance.

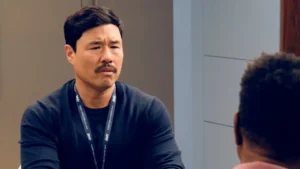

Ejiofor is delivering quite the performance here. Harris is great too, but as someone who at least resembles a human being. Ejiofor is inventing Faraday’s quirks, tics, outbursts, physical mannerisms, and mode of speech on the fly, and the feeling of never quite knowing what he’s going to do next adds a very welcome sense of comedic uncertainty to proceedings. The original novel is quite a serious work and builds to an extraordinarily bleak and cynical ending. While one supposes this adaptation will head in the same direction, it seems intent on having a lot of fun on the way there, which is perhaps just as well.

There’s some unevenness in both the moment-to-moment writing and the wider plotting, but Ejiofor and Harris both sell a sense of frustrated, frantic energy that really works to the benefit of The Man Who Fell to Earth. Faraday’s annoyance at presenting unequivocal facts from a ruined future only to be confronted by mistrust and suspicion is the same kind of thing peddled by an environmental message movie like Don’t Look Up; the disbelief at not being believed, even when supported by overwhelming evidence. Now, as culturally, socially, and politically divided as we’ve ever been, seems as good a time as any to address the theme of our own hard-headedness.