Summary

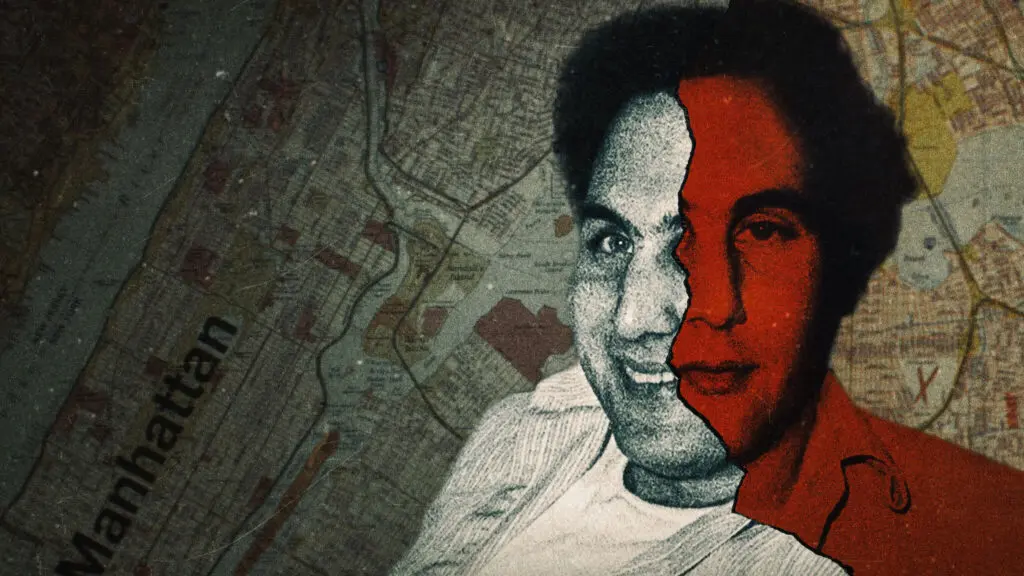

Conversations with a Killer: The Son of Sam Tapes cleverly puts a familiar format to wider use in examining not just the crimes of David Berkowitz but the cultural context that they occurred in.

The problem with David Berkowitz, aka the “.44 Caliber Killer” and, eventually, “The Son of Sam”, is that in a true crime streaming context, he isn’t weird enough. I know, I know — that’s an alarming thing to say about a serial killer. But I’m right and you know I am. Berkowitz didn’t dress up as a clown or eat people or commune with Satan. His whole shtick was being an ordinary-seeming dude. And Emmy-winning and Academy Award-nominated director Joe Berlinger seems to agree with me, since Conversations with a Killer: The Son of Sam Tapes, the fourth in Netflix’s popular series, is as much about ’70s New York as it is the titular killer.

It makes sense. The competition is fierce, with this series having already covered Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, and Jeffrey Dahmer. Judged against the standards of an everyday person, Berkowitz is a lunatic, but in that crowd, he’s almost tame. Uncomfortable though it may be, the essential appeal of these shows is the idea of hearing outright lunacy from the horse’s mouth, but in the audio interviews he recorded in 1980 with reporter Jack Jones at the Attica Correctional Facility in Wyoming County, New York, Berkowitz is pretty even-keel. He calmly explains the genesis of his antisocial outbursts, his particular disdain for women, or at least those he perceived to be like the biological mother who abandoned him, and the formation of the “Son of Sam” identity, which has a surprisingly mundane explanation. All the characteristics that made David Berkowitz an effective serial killer — his rationalism, his self-awareness, and his ability to present himself as utterly everyday — also make him a less-than-ideal interview subject.

But the New York he terrorised is fascinating. Underinvested, wracked by crime, and having been supposedly told by Henry Ford to “drop dead”, the city had become a warren of failing infrastructure and bad actors, with law enforcement in all five boroughs overworked and entangled. The NYPD was so ill-equipped to catch Berkowitz that he took to leaving crazy letters to encourage them, building his own infamy in the meantime, and the randomness of his crimes left the citizenry, especially young brunette women, with a pervading sense of fear. For twelve months, Berkowitz held an entire city hostage, which is the most essential and engaging part of his story.

As ever, that story unfolds in a medley of present-day interviews, reconstructions, archival footage, and the titular tapes, returned to relatively infrequently for Berkowitz himself to add a little pointed context to what he was doing. True insight is a little thin on the ground, but the general banality of it all is, in itself, intriguing. Berkowitz describing how he planned to kill a couple whose car was stuck in the snow, only to end up helping them free the vehicle because they were polite to him, is a genuinely fascinating nugget, because it helps to psychologize a man who needed to be needed above all else. What Berkowitz craved was normality; he spent his life cosplaying a normal guy because he had never felt like one. His hero complex was about wanting to belong, to be helpful, to be necessary. It’s this kind of thing that makes the underpinning idea behind Conversations with a Killer so tantalizing.

But opportunities seem to have been missed. Berkowitz’s rather sudden mental decline around the time he developed the “Son of Sam” persona is explained by a third party, and Berkowitz himself has little to say about it beyond too-obvious observations like a continuously barking dog being annoying. Fundamental to the Berkowitz story is the Jekyll and Hyde component to his character, but this never comes across during the interviews, which are intended to be the selling point. The docuseries has the unusual distinction of being about a man who is the least interesting thing about it.

True-crime fans will lap it up, of course. Aficionados will learn little from The Son of Sam Tapes that they didn’t already know, but that’s never the point of this series, which always seeks to crack a window into the psyche of the world’s worst killers. Berkowitz isn’t the best conversationalist, granted, but Netflix has documentaries like this down to such a fine art by now that simply having the story recounted so effectively is enough to justify a look. There are worse ways to spend three hours.