Summary

WWE: Unreal pretends to pull back the curtain on how sports entertainment is crafted, but it’s a mess of internal contradictions that never manages to escape being a sanitised marketing ploy.

There’s a concept in professional wrestling – or “sports entertainment”, whatever you prefer – known as “kayfabe”. In simple terms, it’s the idea of keeping up the illusion no matter what. Detractors will always say that pro-wrestling is “fake”, but that’s the wrong word. It’s pre-written, sure. The outcomes are predetermined. Most of the big moments are carefully stage-managed. But the physical performances are very real, as are the deeply human emotions threaded through the meta-stories of fulfilled childhood dreams and career swansongs. Kayfabe exists, or at least existed, to protect all that, to fill a moat of ambiguity around the teetering castle of WWE’s industry dominance. And this is what WWE: Unreal gets most fundamentally wrong.

Pro-wrestling is a unique storytelling medium. Its longevity and distinct on-the-fly improvisational quality allow it to craft organic narratives that can stretch across decades. Kayfabe is essential to all that, so you can never truly abandon it, which everyone behind this five-episode trip into wrestling writers’ rooms was presumably well aware of. That’s why it’s so sanitised, safe, and curated. What was advertised as a searing exposé, which would in itself have been a bad idea, is really just an on-brand marketing ploy to coax new viewers following the transition to Netflix on January 6, 2025. And that’s a worse idea, because it’s so cynical, and so antithetical to the spirit of refusing to acknowledge the obvious. David Schultz slapped a reporter for less.

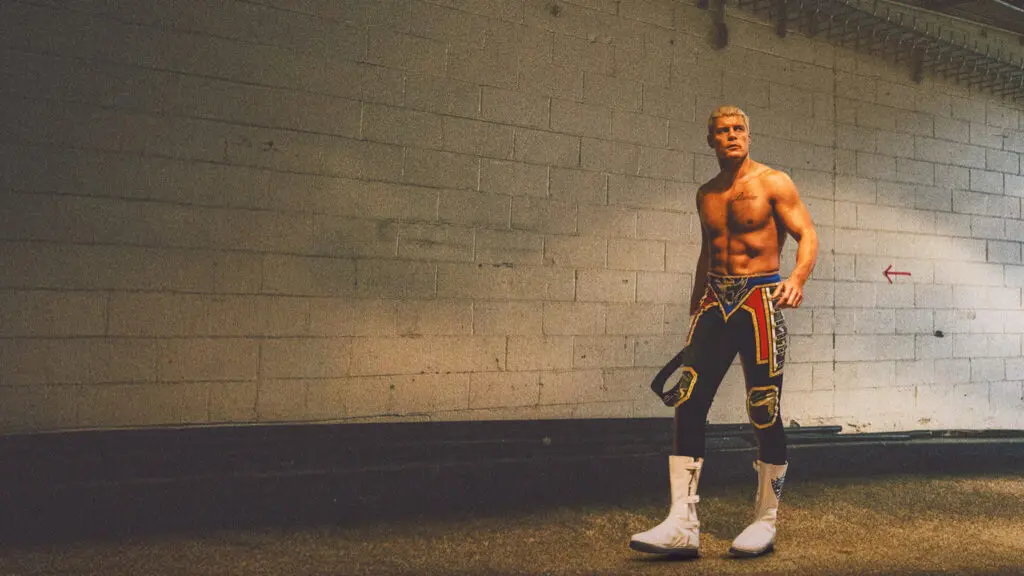

But this is, lamentably, the Netflix era. It’s obvious everywhere. The series charts a timeline from WWE’s Netflix debut to its springtime flagship event, WrestleMania, following various wrestlers and storylines as they develop over multiple matches, promo segments, and backstage interactions. It’s big on recognisable faces, including, unavoidably, Paul “Triple H” Levesque, WWE’s current Chief Content Officer, and trans-media talents like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson and John Cena (seen recently in Prime Video’s surprisingly good Heads of State). But it’s light on the creative friction that was often integral to the development of those characters. You need only look at how quickly the show glosses over CM Punk’s infamous pipe bomb moment, subsequent departure from the company, and eventual return to get the idea. This isn’t a series that’s especially interested in the famously discordant backstage environment that brings pro-wrestling to life, but instead in presenting a well-oiled and unflinchingly professional version of it that tries to leverage the blurred line between live performance and written storytelling.

What WWE: Unreal overlooks, deliberately or otherwise, is how essential the legacy of kayfabe is to how the company operates creatively. There was a time when the only way of getting any information that WWE hadn’t pre-approved for consumption was through dirt sheets, which were often inaccurate anyway. The fact that you never quite knew what was real or what was fake, or to use wrestling parlance, what was a work and what was a shoot, was part of the fun. This series is undeniably a work, albeit one pretending it isn’t, which means it has to constantly reframe details to leverage the idea of pulling back the curtain. It’s an internal contradiction from which the show can never quite escape.

Every now and again, it does a halfway decent job of trying to. A lot of relatable emotion comes from John Cena, of all people, whose frank description of ageing out of the business and hoping his body holds up for a final go-home run is effective. And the particular travails of female superstars are handled decently well, especially focusing on up-and-comers like Chelsea Green. Unreal’s cards are firmly on the table even here, though, with the constant reiteration of Rhea Ripley’s ascendancy being a thinly-veiled way of directing new viewers to the company’s most marketable product. A more interesting angle for a show ostensibly about WWE’s creative process might have been how Ripley, a south Australian who debuted as a kind of androgynous punk-rock bodybuilder, has become increasingly sexualised the more popular and successful she has become, but just as Unreal is completely unwilling to utter the acronym “AEW”, it’s also reluctant to admit what it’s selling and who it’s trying to sell it to.

The frustrating thing is that the behind-the-scenes stuff – especially everything going on in “Gorilla Position”, the staging area behind the entrance where producers and creative coordinate the action in real time – is genuinely more engaging than the in-ring action. There was absolutely a fascinating docuseries to be made about the live high-wire act of bringing these shows to life twice a week, but it’d be an enthusiast product for wrestling die-hards, which, based on the near-constant over-explaining of basic match rules and well-known pro-wrestling concepts, isn’t who Unreal is being marketed towards. Another contradiction, then. Add it to the list.