Summary

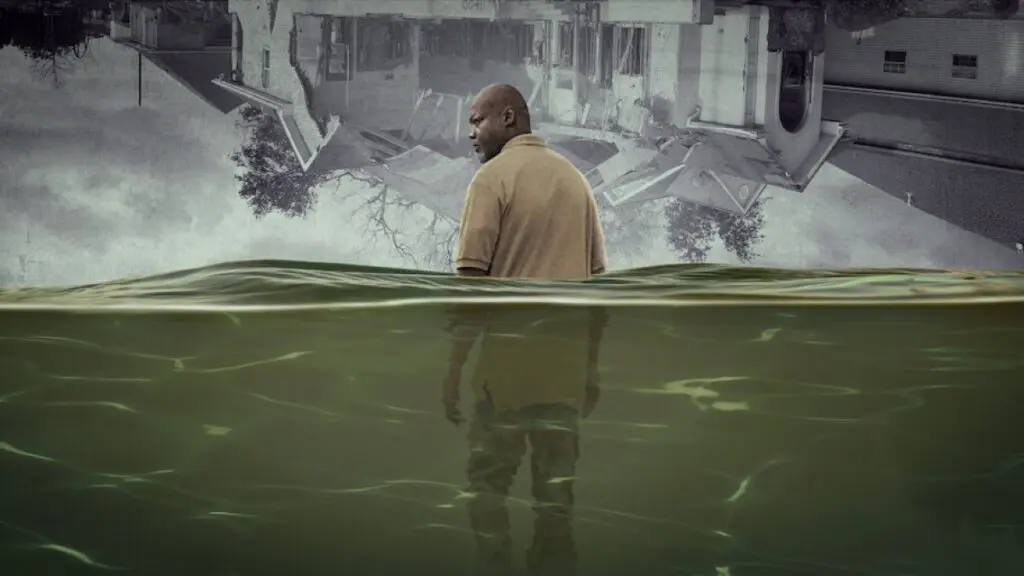

Katrina: Come Hell and High Water has obvious similarities to other recent docuseries on the same subject, but Spike Lee’s righteous indignation comes through powerfully, resulting in a resonant and valuable recounting.

Apparently, documentaries about Hurricane Katrina are like buses – you wait ages for one to come along, and then you get two pretty much at once. Disney+’s Hurricane Katrina: Race Against Time, executive produced by Ryan Coogler, covered a lot of ground in a forensic timeline of the events before, during, and after the disaster. In Netflix’s Katrina: Come Hell and High Water, Spike Lee approaches a lot of the same material with less detail but more righteous anger at the devastation of the event and the racist underpinnings of the overdue relief efforts. It’s a worse documentary but a more impassioned work of filmmaking.

These things also divide the two shows, making them equally valuable and relevant despite their similarities. Katrina is one of those unique events that never wanes in relevance because it wasn’t just a tragic natural disaster of record-breaking scale but also a profound institutional and systemic failure, one tinged with racially-motivated indifference and then a more sinister effort to allow the flood waters to wash away the unique and vibrant cultural identity of New Orleans. This, if nothing else, seems to be impossible, and it’s this nonconformist spirit that Lee chooses to focus on in his brilliant, scathing final episode (of three).

Come Hell and High Water can’t help but use a lot of the same footage and several of the same interviewees as Race Against Time, but it’s better in the build-up and the aftermath, despite being less comprehensive. The essentials are easy enough to grasp, anyway. New Orleans was no stranger to hurricanes, but its levees and drainage systems were designed to counteract a Category 3. Hurricane Katrina, which struck on August 29, 2005, was a Category 5, and it’s probably worth noting that the scale doesn’t go any higher. Prior experiences with smaller hurricanes that veered away in the final moments gave the populace misplaced confidence. By the time the severity of the situation was clarified, it was too late. The mandatory evacuation was too delayed to be effective and was essentially impossible to enforce anyway. Most residents of the impoverished, primarily African-American neighborhoods, lacked the money to move regardless. The water cleared the levees, flooding entire districts, and thanks to the bowl-like shape of New Orleans, it had nowhere to go. 1392 people died.

And nobody, it seemed, cared a great deal about this. The Bush administration met the disaster with characteristic disinterest, and the public framing of its aftermath took on a tone of accusatory finger-pointing and racist propagandising. The implications were clear. A flooded community was “out of control”; desperate attempts to procure life-saving supplies were “looting”. The racial makeup of the majority of the victims could only mean one thing – that, on some level, they must have deserved it.

This is foremost in Spike Lee’s ire over the situation and particularly its aftermath, when insurance companies, banks, politicians, and wealthy citizens picked the bones of devastated neighborhoods to rebuild New Orleans in their own image. Federal funding was allocated not by need, but to according to the original value of destroyed buildings, directing the money towards citizens who were already wealthy in the first place, leaving the poor Black communities to rot while the middle classes left for pastures new. Crime spiked, many residents were imprisoned, and their homes were gentrified. The floods damaged the infrastructure, but the state continued to feast on the culture long after the water receded.

Spike Lee gets this intuitively, and in its best stretches, Katrina: Come Hell and High Water vibrates with righteous indignation but also hope for the indefatigable spirit of New Orleans. There’s no happy ending here, but only because there is no ending at all – the city, its people, and its culture endure.