Summary

Twisted has a good underpinning premise, but it’s a weird movie overall trapped between many competing genres and ideas.

Twisted (2026) is one of those interesting inversions of home invasion horror, where the seemingly unsuspecting mark of a couple of opportunist grifters turns out to have more in store for them than they bargained for. Think of Don’t Breathe – but ideally not its sequel – or better yet, Barbarian. Just filter that idea through some quasi-Giallo stylistic beats, all canted camera angles and occasionally gaudy uses of colour, and you have a pretty good idea of how this movie looks. But how it fares holistically is a bit harder to explain.

Coming from Darren Lynn Bousman, primarily of Saw fame, you’d think this would be a movie that would rejoice more in a torture-porn sensibility that I never really got from it. It’s aspiring to something a bit more cerebral and morally nuanced, though “aspiring” is the key word there, since it doesn’t achieve it. I appreciate the effort, but the ways in which it strives and ultimately fails make it an odd little film to consider.

Let’s just get the plot stuff out of the way. Paloma (Lauren LaVera, Terrifier) and Smith (Mia Healey, The Wilds) are con artists running a fairly lucrative scam to rent out well-appointed properties to dopes who are seduced by their charms and good looks, not realising they’re paying for six-month stays in homes that were never on the market in the first place. The screenplay doesn’t dig too much into the specifics of how this scheme works, which is perhaps just a well, since there are about a million ways in which it quite clearly wouldn’t. But just roll with it.

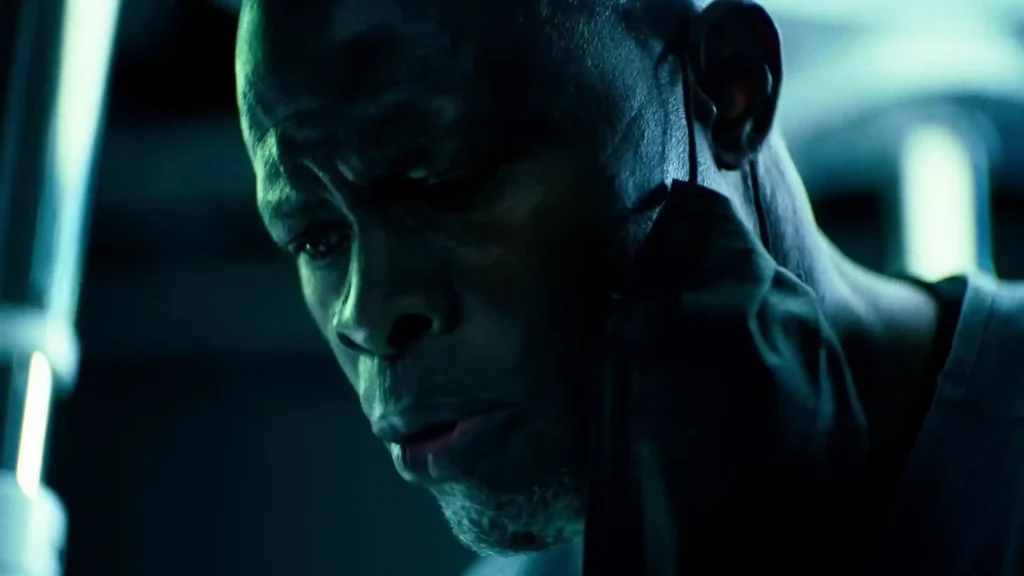

Paloma and Smith – who are in a relationship, by the way, a fact that is mostly used for cheap titillation in the early going until the third act when we’re supposed to swallow that it was a genuine love story – set their sights on a lovely brownstone owned by Dr. Kezian (Djimon Hounsou, Rebel Moon), a famed neurosurgeon still smarting from the death of his equally accomplished wife. Paloma moves in, but quickly discovers that Kezian is up to some rather morally questionable things in the property. And now she’s an unwilling part of them.

So far, so familiar. The inversion of the predator and prey dynamic is effective enough, but nothing new, though after a while, it ceases to be the point. There are problems even here, though. Paloma’s Final Girl status is a bit difficult to buy into since you never really feel compelled to root for her, and Kezian can come across as a bit of a weak antagonist because he still has a spark of humanity about him, and he never really commits to doing anything that monstrous. He’s a bad guy, without question, but Twisted is trying to highlight his human side and emotional baggage so we understand why he’s doing what he’s doing.

This is where the movie suffers the most, I think. It feels trapped between all these warring genres and ideas, never quite committing to any of them strongly enough to make an impact. You can’t classify it as really taut home invasion horror, since Paloma becomes a fairly inert captive pretty early. It doesn’t have the schlocky B-movie uber-violence you might be expecting. But its attempts at moral nuance aren’t great either, so it ultimately ends up being a substandard version of a handful of things instead of a better version of just one.

It makes for a frustrating experience overall, which brings the cliches – in both the writing and direction – into starker relief. These simply aren’t very interesting characters. Neal McDonough (Tulsa King) is here for, like, two scenes (not playing the bad guy for once), but even he fails to really liven things up. LaVera is game, and Hounsou is effectively chilling, especially in the third act when he’s allowed to go a bit bigger with the portrayal, but it’s just a strangely tame movie given how macabre and potentially even thought-provoking it might have been in different circumstances.

Bousman does a good job with the setting – a late reveal even contextualises some bits that initially seem like giant contrivances – and there is some fun, nasty stuff eventually. Anyone who doesn’t enjoy the sight of exposed brains need not apply, though. There’s a lot of that particular visual, enough to make you wonder where the prop department acquired such a considerable supply. Perhaps the writers?