Summary

David Yarovesky proves again with Brightburn that there’s no concept so intriguing that his lack of ambition can’t squander.

Sometimes a movie feels like it was created with passion, and sometimes it feels “pitched.” Brightburn is a pitch film, one that sounds like an idea a couple of dudebros stumbled on somewhere around their fifth beer. A “Superman horror movie” might lure you to the theater, but whether or not Brightburn felt like another Screen Gems scam, in the end, depended on whether director David Yarovesky could find more in that concept than the pitch. He could not.

I recently saw and reviewed his first film, The Hive, which was a stale twist on slasher movies with some gore garnished on top. Not only does Brightburn follow the same pattern, but the words “the hive” are spoken in this new movie within the first six minutes. I was wondering how I would describe Yarovesky as a director and when the schoolteacher says those words at the end of a dramatic sentence, I knew how to do it: he’s the kind of artist who can’t recreate anything but the simplest genre tropes and he already thinks he’s making an oeuvre worthy of self-reference.

Brightburn makes its first mistake before it even starts. Its mistake is in marketing.

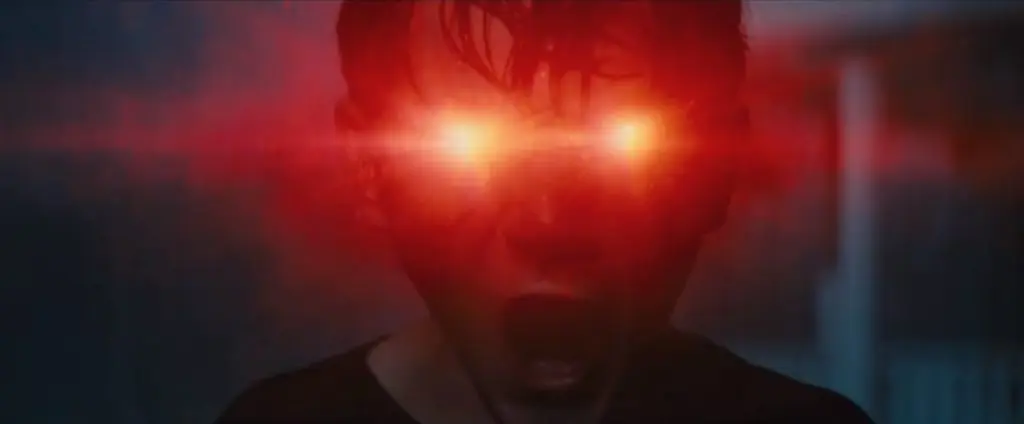

Everyone knew going into this movie that it was a Superman horror movie: that’s how everyone knew this movie to begin with. Creating dramatic tension in Brightburn required that we not know that for the first half of the film. But since we know everything about this movie already – he’s a Superman clone except that he’s evil – there’s absolutely no thrill in the mystery of the movie’s first half. We know what’s in the barn and what it will do to Brandon (Jackson A. Dunn). I found myself bored waiting for the bloodbath to start.

What Brightburn really misses in this crucial first half is a sense of Brandon’s goodness, or his desire to be good. He says the word “good” a few times, but it’s hard to believe him. He’s sweet at the beginning, but from the moment the spaceship turns on and tells him to be a villain, he’s Damien from The Omen. The nice boy never comes back, not for guilt or even for vengeance. This is when the only concept that could have improved Brightburn disappears, and we’re left waiting for the gore.

What this film really needed was a sense of what his great power convinces him to do despite his good upbringing. Or, as a different twist, perhaps his parents could have been abusive, turning our little Superman into a Damien. The purpose of any of this would be to explore the Superman concept: what people do with great power, what is in our natures that makes us act the way we do, and how experiences influence our beliefs. Instead, Brightburn equips Brandon with an ideal upbringing – though bummy, Elizabeth Banks and David Denman have endearing chemistry, like a couple of woodland bears that you blame for nothing. At the beginning of this movie, he seems like a good little kid. When the probe “changes” him into an evil monster, it absolves him of his responsibility for being evil and the parents of the possibility that they did anything wrong. Writers Brian and Mark Gunn are absolving themselves of thinking about this too hard.

Brandon discovers he has superpowers in a flimsy scene involving a lawnmower. He accidentally throws it across a field and his next inclination is to grab the spinning rotary blades (he does so off-screen). This is a kid who’s read Superman comics, though no one in this universe acts like they’ve heard of superheroes. Why does he think those powers would be correlative? I imagine someone would say that the voices in his head are telling him that they are: at that point, the aliens are basically just subbing for the writers.

Of course, there’s a trap here: there must be more to Brightburn than what we expect of its premise. Likewise, criticism can’t center only on what I’d hoped it would do based on that juicy idea of a Superman twist. So let’s ditch Superman for a minute. How good is this movie, just as a slasher film in 2019?

Brightburn is full of jump-scares, false scares, and lead-ins on the soundtrack, something which I believe turns a scary situation into a predictable jack-in-the-box. You can count down to the scares in this movie. It’s no different at the beginning when Brandon is playing hide and seek with his mom but this part works in a chilling way, by putting Brandon in a scary context before there’s anything to be scared of. It’s the only time that our foreknowledge of where this is going actually increases the tension.

Michael Dallatorre shoots the movie competently; there are far uglier horror films out there. But since Brandon’s change isn’t meaningful, no amount of composition can give this opening more meaning either. It doesn’t hide the terror of the situation; that terror simply doesn’t exist yet. This movie is stuffed with cheap horror house stuff in general (he’s there, and then when you turn on the lights, he’s gone!). It’s never scary even a little (there’s a Raggedy-Anne doll printed on the wall, a reference to Anabelle perhaps, who was a Raggedy-Anne in real life, but Yarovesky forgets that James Wan is a true horror technician on those Conjuring movies; it would be like putting a Casablanca poster in The Hustle).

But that’s not the real issue: Brandon, the way the writers conceived him, is what drags Brightburn down. The horror of male puberty is a standard trope in slasher movies. Michael Myers was six years old when he killed his sister in Halloween. They locked him up for fifteen years before he came back, finally of age to use his big knife to punish people for having sex without him. That was way more potent than Brandon’s transformation because it challenged our idea of childhood, which Brightburn believes it’s doing but never does. Imagine if Michael Myers or Kevin from We Need to Talk About Kevin were aliens, as though they weren’t responsible for the tension they cause, and we weren’t either. Kevin was a film that terrorized not only a mother but the very concept of being a mother in the first place. Brightburn is one wheezy little note of Kevin’s horror symphony.

It asks the question of whether Superman is evil but not as though that tells us anything about human nature. It boils down basically to: what if an alien came to earth … and was hostile? They’ve been making horror movies about that for forever. Brightburn needed to be careful not to support the xenophobia that modern Superman movies debate and condemn but it absolutely does: it is an argument for considering a foreigner evil because of his foreignness, not because of his upbringing or even his own character as an individual. Horror movie people always do stupid things. The only stupid thing they do in Brightburn is love someone that isn’t human.

The movie is accessorized by some surprises. The gore, for instance, is ratcheted way up: there’s a close-up scene of a skewered eyeball that recalls The Andalusian Dog, Dali’s old short film made to make people question their existence and possibly barf about it. Why does Brightburn do it? Matt L. Jones (you might remember him as Badger from Breaking Bad) plays a part that Yarovesky clearly can’t figure out. In a moment of extreme duress (it’s in the trailer), he says things like “Aw, man” and “Oh, sh**” and the people in the theater were laughing. It’s hard to figure out what to feel during this movie. True bodily grotesquerie – the theater was filled with the slurping sounds of someone gagging on their own blood and teeth as their body parts fell off – might be preceded by corny humor in Brightburn. It’s the kind of movie where the most intense parts illicit laughter over the pleasure of being grossed out, rather than terror over the cost of thinking about something. Only one moment hits that sublime sweet spot of dark comic horror technique: a person is about to be pummeled to death and the camera cuts to a bowl of oatmeal. It’s often better not to see it.

It’s weird how this movie was advertised as being so creative and edgy when the exact concept has already been done so much better: Josh Trank’s Chronicle was exactly this but with the addition of the hero’s voice in deciding whether he should be good or evil and for what reason. Brightburn acts like it answers the question, “What if Superman was evil?” but it actually does much less. Instead, it asks, “What if a slasher villain had superpowers?” That’s the extent of its imagination. The reason is that the script never deals with Brandon in an intimate way and why he does what he does; as soon as the plot engineers a way for him to be different, none of his experiences seem to matter. Not even the bullies matter, who bother him at the beginning; the writers don’t even make his retaliation or angst a theme by bringing them back into the fold once Brandon is powerful. Brandon is given the chance to do so little based on his own beliefs or experience that if Clark Kent himself was taken over by an alien probe (which I’m sure has happened at least once), the results would be the same. That’s how little a “twist” on anything this really is.

And if Brightburn is more like The Omen or Kevin, the missing element is the voice of the mother: Banks, playing the mom as a kind of quirky parody of Parker Posey, isn’t given a lot of time to face her own feelings in this movie. We don’t get a sense of her struggle even though none of the performances thwart that possibility. Banks is appropriately exertive. Dunn is passable as a deadpan evil kid. Denman is a friendly grizzly, the kind of guy that the people who pine after the Banner/Hulk hybrid in Avengers: Endgame will think is really yummy.

Brightburn is a brisk 90 minutes, almost like it doesn’t have time to build to anything: the ending has the same hurry in it that a carnival man has when he rolls up his exhibit and gets out of town before people realize it’s a sham (you can always spot this kind of illusion when you see the trailer and notice how prominently it features its famous producer rather than its director). The problem really is the script. Even those who want something specific from Brightburn – those who laugh at the gore, especially – won’t be happy with how it ends. They’ll want a payoff. If they had gotten it, they’d probably have also gotten the double “B” symbol the movie really wants you to think is a “thing” tattooed on their ankle. Some of them probably still will. I honestly have no idea who would like this movie. Those who know the value of a good pitch, I guess.

More Stories