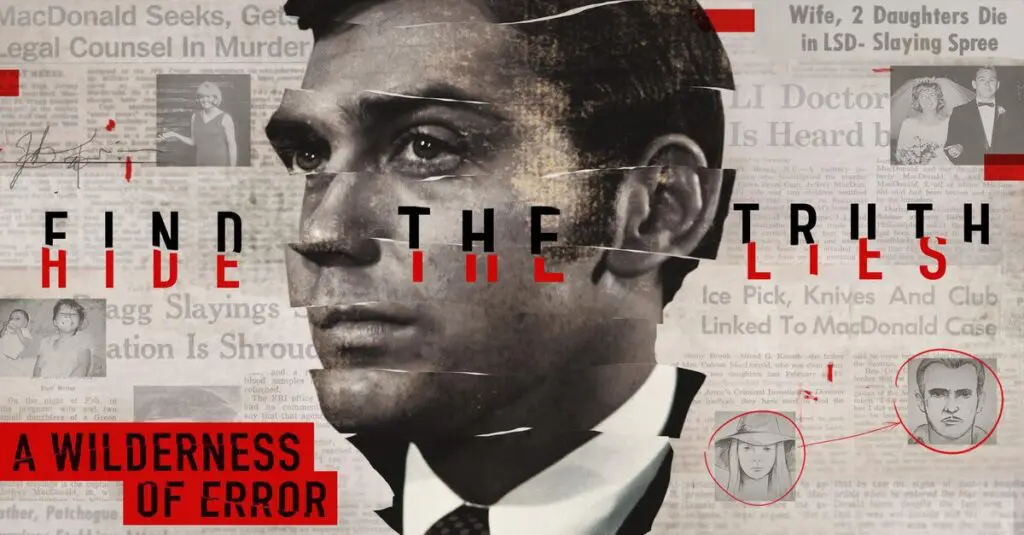

Summary

A Wilderness of Error is an atypical true-crime docuseries that interrogates the form itself just as much as the case in question. It’ll divide audiences, and so it should.

This review of A Wilderness of Error is spoiler-free.

It’s only a coincidence that I’m reviewing FX’s new true-crime docuseries A Wilderness of Error the day after Netflix’s A Perfect Crime, but it’s a fitting one since I said in my write-up about the latter that true-crime as a genre has a duty to not just the truth but to entertainment. The question of how much of what you’re seeing has been deliberately arranged to drum up renewed speculation and engage an audience is ever-present in this format, and it’s addressed directly in this new series by Marc Smerling.

A Wilderness of Error, then, perhaps obviously given the title, is about not just the crime but the way that crime is repackaged as entertainment for a mainstream audience (Smerling himself was a producer on The Jinx, which received its fair share of criticism.) The crime in question is the 1970 murder of Green Beret doctor Jeffrey MacDonald’s pregnant wife and two daughters, ostensibly by a Manson Family-style gang of hippies led by a woman in a floppy hat.

Of course, nothing is ever that simple, and the idea of drama and a drummed-up narrative is integral to the case itself, not just this exploration of it. As explained by Errol Morris, from whose same-titled book the series takes its name, the idea of convenient narrative works hand-in-hand with human beings’ innate stubbornness and desire to make things fit. If a story makes some degree of sense, and it plays on prevailing cultural currents, people will be inclined to swallow it wholesale. This is the means by which killers try to cover up and get away with their crimes. It’s also the impulse on which true-crime as a genre functions.

As the so-called facts of the case are challenged in turn, the mechanics of true-crime are also interrogated. The blurring of the line between recreation and entertainment is examined. The likelihood of personal bias is brought up. Each conflicting theory is presented as equally viable and their knock-on effects, not just their evidentiary basis, are considered also. In a sense, this format is mimicking the justice system itself, following every red herring and loose end to a nest of more questions and theories. A Wilderness of Error doesn’t take a side or present its own theory; instead, and intentionally, it posits that the “what if?” questions so inherent to the appeal of true-crime can just as easily be “what if this case is completely cut and dry and there’s no mystery here at all?” as any kind of broader conspiracy. Not knowing is, in and of itself, powerful enough.