Summary

Flashback is well constructed and capably performed, but its stylish excess obscures a lack of depth and substance.

This review of Flashback is spoiler-free.

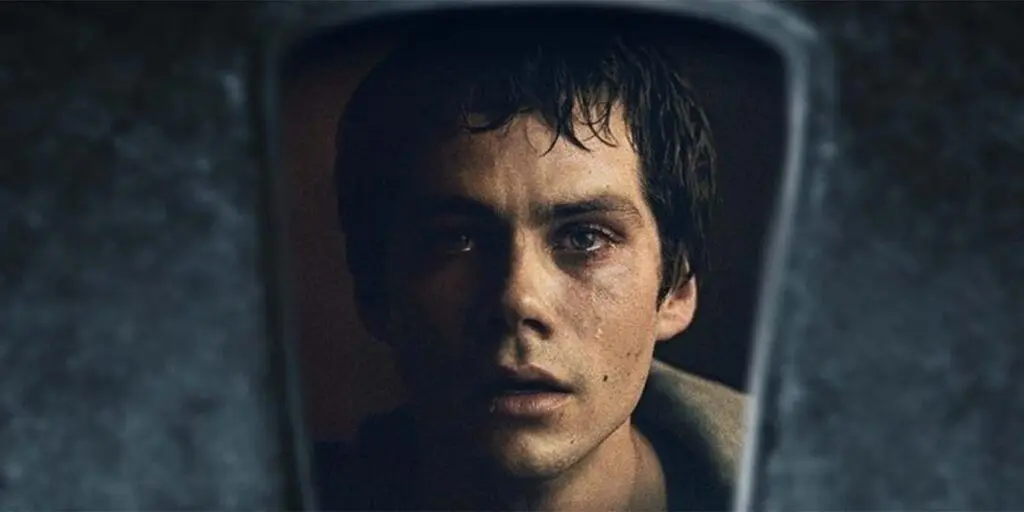

Dylan O’Brien is lucky enough to have been blessed with a handsome babyface, which is probably what got him sucked into the young-adult franchise machinery of The Maze Runner and its sequels. The downside is that people equate all his success with his good looks and don’t appreciate that he’s a pretty decent actor. Netflix’s recent Love and Monsters went some way towards proving that, and writer-director Christopher MacBride’s second feature, Flashback, might be his most interesting work yet.

It won’t appeal to his usual audience, though. A surreal patchwork of intermingling realities, it’s one of those too-clever-by-half puzzle box narratives that uses a lot of style to obscure too little substance. It’s still being released in some markets under its original title, The Education of Fredrick Fitzell, which feels more fittingly pretentious for an admirably constructed film that nonetheless disappears into an alternate reality of its own backside after a while.

It’s fun until it gets to that point, though. O’Brien plays Fred, a nondescript IT dude who shares a functional but characterless apartment with his girlfriend Karen (Hannah Gross). He’s hardly happy-go-lucky when we meet him, but he’s thrown a loop by his dying mother (Liisa Repo-Martell) losing her memory of him. Compelled to re-examine his past, he realizes that he’s perhaps reliving it and that a designer drug called Mercury that he and his buddies experimented with 15 years earlier might be to blame for both his current experiences and the disappearance of Cindy (Maika Monroe), whom Fred had a crush on at the time and nobody has seen or heard from since.

With the help of two former classmates, Sebastian (Emory Cohen) and Andre (Keir Gilchrist), he begins to explore his childhood and slips deeper and deeper into a fusion of past and present, as though he stepped through a portal – a theory posited by Flashback itself – into a confluence point of various realities. The filmmaking matches the increasing weirdness of Fred’s experiences with an increasing overuse of psychedelia and surrealism, and it’s easy to lose track of both the plot and the point as things progress. O’Brien is good, as usual, but he’s also playing a cipher rather than a character, a troubled young man whose purpose is to justify the film’s structural and storytelling flourishes rather than discover anything meaningful about himself, his friends, or the world(s) they all inhabit.