Summary

Midnight Mass is preaching to the choir somewhat, but those who get on its wordy wavelength might just find it Mike Flanagan’s best, most contemplative work yet.

This review of Midnight Mass is spoiler-free.

Netflix is so well-suited to writer/director Mike Flanagan’s specific form of slow-burn, talkative horror that the latest release from him is beginning to feel like an event. After the success of The Haunting of Hill House, The Haunting of Bly Manor was welcome proof that he hadn’t just struck it lucky. Midnight Mass, then, is eagerly anticipated, and the streaming giant has spared no expense in promoting it. The seven episodes – all, predictably, a touch overlong – have nothing to do with either of the two preceding series’, despite being populated by a number of familiar faces, but the eager binge-watching crowd will no doubt power through them all the same. Many will be put off by it. But some, and I think I count myself among their number, will find it the best work Flanagan has ever put his name to – provided they can get on its verbose, contemplative wavelength.

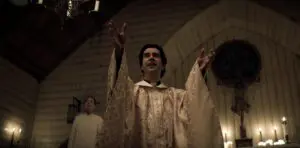

Midnight Mass is contemplative about many things – life and death; love and hate; Heaven and Hell – but what it primarily has on its mind is Roman Catholicism, and when I say that a healthy contingent of devout Catholics will be extremely annoyed by it, that shouldn’t be taken as an understatement. Our initial point-of-view is that of an atheist, Riley Flynn (Zach Gilford), who despises his former religion and indeed his isolated and deeply pious hometown of Crockett Island, aka the Crock Pot, a community comprised of mainly blue-collar fishermen whose population of 127 is dwindling after an oil spill decimated what little industry was available there. All that remains on the island is faith, which is just as well, since their new priest, Father Paul Hill (Hamish Linklater doing the best work of his career), can apparently perform miracles.

Riley is a former altar boy who lost his faith after his alcoholism led to the death of a young woman and a stint in prison. There are few like him on the island. Most are committed believers, with some, such as Samantha Sloyan’s wonderfully detestable Bev Keane, so devout as to border on fanatics. For several of the early episodes, Flanagan focuses on building this community, giving us a sense of its history, its current predicament, and the people who continue to cling to it, perhaps against their better judgment. There are too many important characters to name here; almost everyone has a part to play, however small, in what follows – and what follows might not be entirely what even devoted fans of Flanagan expect.

For one thing, monologues. Midnight Mass is full of them, and a couple – one shared by Riley and Father Paul about why the former lost his faith, and another between Riley and his old flame Erin (Kate Siegel) about what happens after we die – are striking. Oftentimes the show indulges itself by allowing these soul-searching diversions to go on much longer than any real conversation would; sometimes they take on a fanciful, dreamlike quality as if the characters aren’t talking to each other but to whatever deity they lost their connection to. I never thought I’d say it, but these scenes, far more than the obligatory jump-scares, gruesome imagery, or all-action climax, strike me as the most memorable.

They won’t be to everyone’s tastes, granted, and the show isn’t, at least on a superficial level, scary. But it finds terror in its contortion of Catholic staples such as Holy Communion, and the idea of unwavering belief as an excuse for bigotry and fanaticism. It’s deeply critical of religion in general and Catholicism specifically, even while it finds the beauty in a haunting rendition of a hymn or a moment of real faith. I wouldn’t quite declare it anti-religion, but at least a cautionary tale about becoming too complacent to interrogate one’s own beliefs. And the patience Flanagan exhibits in the early going allows for the show to mostly subvert the cliché of God-fearing isolationist islanders and avoid lazily equating piety with stupidity. It does, in simple terms, make you think, and it rewards your consideration with a number of powerful character moments, some of which, such as everything involving the town’s Muslim Sheriff, Hassan (Rahul Kohli), who is mostly on-hand to provide the perspective of a non-Christian believer, work far better than they have any right to.

Many of the show’s weaker moments are saved by some exquisite performances, particularly from Linklater, who turns the trope of the enigmatic holy man on its head, as well as a tremendously warm and likable Kate Siegel. Even comparatively minor figures, such as the town’s boorish alcoholic, Joe Collie (Robert Longstreet), are surprisingly layered and nuanced. Eventually, you come to care about almost everyone, which makes the long-awaited climax surprisingly effective. The fact it pays off almost every plot thread and theme isn’t just atypical of Netflix’s original series’, but of the genre in general, and Flanagan makes a well-worn framework that much more compelling by simply taking the time to really explore it, for better and for worse.

More Stories