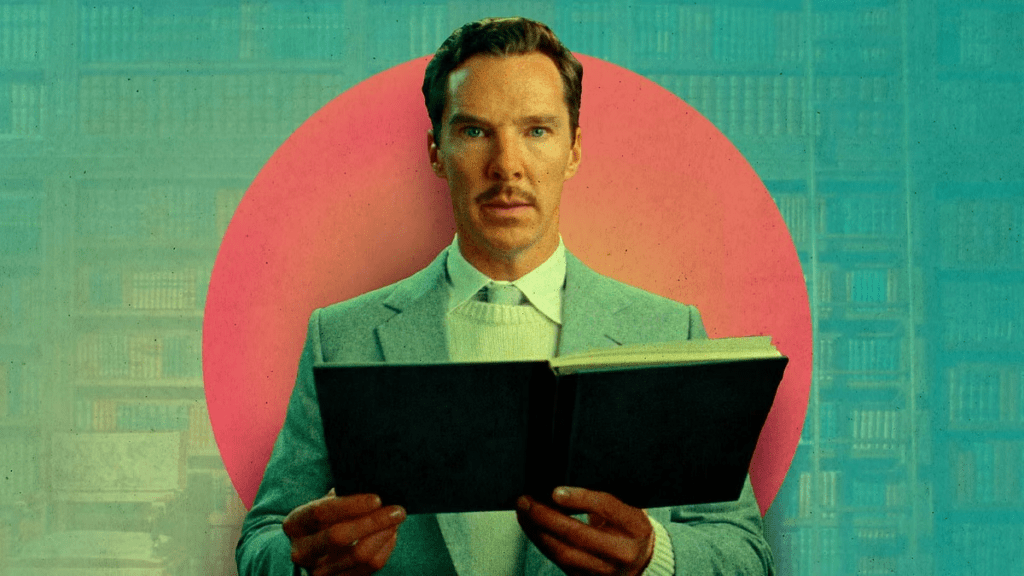

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar combines the best of both Roald Dahl and Wes Anderson in a 40-minute Netflix short. The first of four Dahl adaptations for the streamer, it’s certainly a clear metaphor for greed and the dissatisfaction of unearned success, but, in true Anderson fashion, its nested storytelling leaves certain elements deliberately unclear. Allow us to walk you through the ending of The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and unpack some of its obvious and subtler meanings.

Naturally, spoilers to follow.

The plot of the short film revolves around the titular Henry Sugar, a wealthy bachelor who teaches himself the ability to see without his eyes and uses it to swindle casinos out of their money.

The story is told in a theatrical reading of Dahl’s original work, pretty much word for word, though with some of Anderson’s structural flourishes. As we change perspectives, new characters take over the narration and we, as the audience, step into their story, with stagehands quickly shuffling around props and furniture to complete the effect.

We begin with Dahl himself, introducing us to Sugar from Gipsy House and claiming, not for the first time, that it’s all true. But is that the case?

Is it a true story?

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar is not a true story. It’s a work of fiction, but the pretense of authenticity is baked into it. There are claims that Henry Sugar is a pseudonym for a real man whose name has been changed to protect his well-to-do family. It’s a fun gimmick, but also untrue.

This is also the case for other supporting characters such as Dr. Chatterjee and, yes, Imdad Khan, although the idea of being able to see without eyes – either due to blindness or in some other, more performative way, as depicted here – is not entirely unheard of.

How does Henry learn to see without his eyes?

Early in the film, Henry steals a notebook from a library that contains the first-hand account of Dr. Chatterjee’s work with Imdad Khan, a traveling circus performer who had developed the ability, through years of practice under the tutelage of a Yogi, to see with his eyes completely obscured.

Henry mimics the practices laid out in the notebook and finally manages to learn the ability himself, which he subsequently uses to steal money from casinos. The short film takes deliberate shortcuts to obscure how this ability works, implying that it’s simply a matter of patience and practice when it’s really just a bit of hokey magical realism to support the story’s underlying point about the worthlessness of ill-gotten gains.

Why does Henry give away his winnings?

As early as Dahl’s original description of Henry, we’re told that he has never worked a day in his life and that he has a compulsion for gambling. What he swiftly realizes after defrauding the casino is that knowing the outcome in advance spoils the thrill of gambling and that his finally exhibiting some effort to learn how to do something causes him to see the easy path as suddenly valueless.

Dahl also establishes early that Henry – and indeed all rich men – will never have enough money and will always chase the next windfall to add to their already sizeable fortunes. Henry takes this to such an extreme that even the prospect of more money fails to thrill him, and he decides to give the cash away instead, throwing it from his balcony.

Having lived his life as a very rich man, Henry eventually dies without a penny to his name, having lived a much fuller life spending money as opposed to hoarding it.

Read More: