Summary

Pluribus is the rare show that gets better the more you think about it, something evident in Episode 4’s complex relationship with honesty.

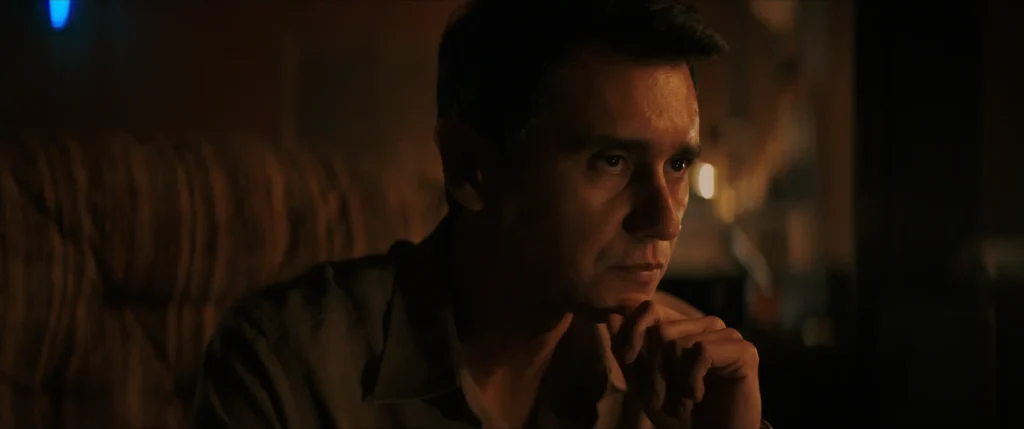

Pluribus makes the cold open an art form. There have been some all-timers already in this season – the one in Episode 2 springs to mind – but the first ten minutes of “Please, Carol” take the cake for me. It’s a lovely near-wordless stretch introducing Manousos (Carlos Manuel Vesga), the Paraguayan self-storage facility manager Carol swore at over the phone. He has taken to Vince Gilligan’s happy-clappy alien invasion rather well, holing himself up in the office and remaining stoically – albeit unhygienically – isolated. His cameo isn’t an accident. It’s a counterpoint to Carol’s ongoing arc throughout Episode 4 as she tries to navigate her relationship with the Others by teasing out the boundaries of their unflinching honesty and need to please her.

Manousos steadfastly refuses to interact with the Others; Carol has had no choice. Carol’s sweary outburst over the phone – which “Please, Carol” shows from Manousos’s perspective – was a personal failing for her, a loss of control after being cautioned about the wide-reaching ramifications of her emotional outbursts; for Manousos, it was a glimmer of hope that there was someone out there like him, an “Other” to the Others. But there are parallels, too. Manousos rigorously notes down radio frequencies; when we shift to Carol, she starts a whiteboard of notes listing things she has learned about the invaders.

Lovely storytelling, this, lean and economical enough to feel mysterious while also containing in that ten-minute stretch a pretty complete thesis on what the entire episode is about: Manousos’s solitude and complete refusal to engage versus Carol’s unavoidable inclusion in a society she can’t fully understand but is developing increasingly mixed feelings for.

Carol’s efforts to collate all of the information she has gleaned thus far hit some snags, and her potential solutions are disquietingly close to self-penance, as if she’s trying to figure things out by inviting as much discomfort on herself as possible. Because of how things work in this world, it’s impossible to tell whether this is a manifestation of Carol’s survivor’s guilt, a purely practical acknowledgement that the only way she can stress-test the limits of her overseers is by challenging their dynamic with her, or, most likely, some combination of the two. Either way, it manifests as a string of scenes that Rhea Seehorn is miraculously good in.

The first is a conversation with Larry, a seemingly innocuous Other in cycling shorts, whom she sits down and interrogates, lightly at first, about the quality of her books. Of course, the Others love her work, considering it on a par with Shakespeare, a sentiment that Carol finds deeply disingenuous. But it’s a crucial insight into how the Others think. It isn’t about the quality of the prose – Larry recites some, and it’s terrible – but what that shoddy writing means to lonely women in Kansas City (or wherever) whose lives were saved by Carol’s Wycaro books. The Others haven’t just assimilated likes and dislikes, but the most profound depths of feeling. It’s part of what Carol is struggling with. On some level, she wants the Others to tell her that her writing is garbage, but they’re incapable of doing that, not just because they’re trying to keep her sweet – although they are – but because they’re operating on a more complex level than simple preference.

So, Carol changes the terms. She asks Larry to tell her what Helen specifically thought of her books, especially the unpublished Bitter Chrysalis, her magnum opus freed from the trappings of airport genre fiction. And she was unimpressed. It’s a bitter pill for Carol to swallow, both that her best friend consistently lied about her writing to continue reaping the lifestyle benefits it afforded her, and that Carol isn’t very good at the thing she has defined herself by. But it gives Carol insight into how she can use this unflinching honesty to her benefit in the hopes of reversing the Joining. The key issue is that you can tell she still doesn’t quite understand how the hivemind works. Even in her recruitment of Larry, she overlooked the mayor, who was outside cleaning up her front yard, since she didn’t trust a politician to be honest with her. She still can’t rationalise the idea that any Other is a mouthpiece for their entire shared consciousness, stripped of everything that makes them an individual.

But there’s an opportunity nonetheless, one that Carol pursues in Pluribus Episode 4 in a number of creative ways, first by visiting Zosia in the hospital and asking her outright if the Joining can be reversed. The Others can’t lie, after all, so even though Zosia dances around the issue, her refusal to simply say “no” proves it’s a possibility. Carol can tease that possibility out, but it’ll take some creative thinking. In the meantime, she unburdens herself of a core memory that goes some way towards explaining why she’s so reticent to blithely accept the idea of “assimilation”; when she was younger, she was sent to a conversation therapy camp full of “some of the worst people I have ever known.” Those people “smiled all the time. Just like you.” To Carol, normalcy has always been a con; niceness always a ploy.

Carol turns to Pentothal, commonly considered to be a truth serum, hilariously spiriting it away from the hospital pharmacy under the guise of trying to secure heroin (building on the grenade thing in the previous episode, Carol is learning how to make the Others do what she wants by pretending she wants something else). She administers the Pentothal first to herself, recording her own ramblings to check its efficacy as she freewheels through her feelings about Helen’s opinions on her books and Zosia’s general “fuckability” – Seehorn is so good here, both in the video and in her reactions to it – and then she administers the serum to Zosia herself in the hopes of getting her to inadvertently admit how the Joining can be reversed.

This last bit backfires, since Zosia slumps into cardiac arrest without revealing anything. Has Carol found a weakness in the Others here, in the idea that they can be isolated and manipulated? Or a weakness in herself, in that she can’t quite consider them as anything other than individuals even now? As soon as she’s asked to step back so the Others can save Zosia, she acquiesces, since she has clearly come to like her a bit and doesn’t want to see her die. Every effort Carol makes to deduce the hivemind as an alien menace that can be toppled, the closer she comes to being assimilated under her own nose.

RELATED: