Summary

As a subtle actor’s showcase Foxcatcher is undeniably a triumph. Every frame is dripping with sincerity and an almost palpable sense that something awful is approaching.

When I sat down to watch Foxcatcher, ready to review, I had no knowledge of Foxcatcher. Didn’t know it was a real-life tragedy; I had no idea the movie was based on a true story at all. And I think, honestly, that deepened my appreciation for not just where the story ultimately goes but how sincerely (and, in many ways, mundanely) director Bennett Miller chose to present it.

Foxcatcher bleeds color. It’s detached and observant. Quiet. Deliberate. Characters shuffle from scene to scene like mourners. Eventually, the movie depicts a funeral, but it feels like one from the very beginning.

I suppose that constitutes a spoiler. The case is twenty-odd years old and the details are public record, so you can’t be too upset, but I’ll refrain from mentioning anything specific. The cutting and the writing and the seriousness and the mystery of it all keep you curious about where things are headed. Part of the experience is letting the movie show you when it gets there.

Foxcatcher Review and Plot Summary

Before that, there is a sprawling Pennsylvania country estate where John E. du Pont (Steve Carell), the heir to a multi-million dollar chemical and weapon company, has built a state-of-the-art training facility for a team of freestyle wrestlers who he plans to bankroll all the way to the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games.

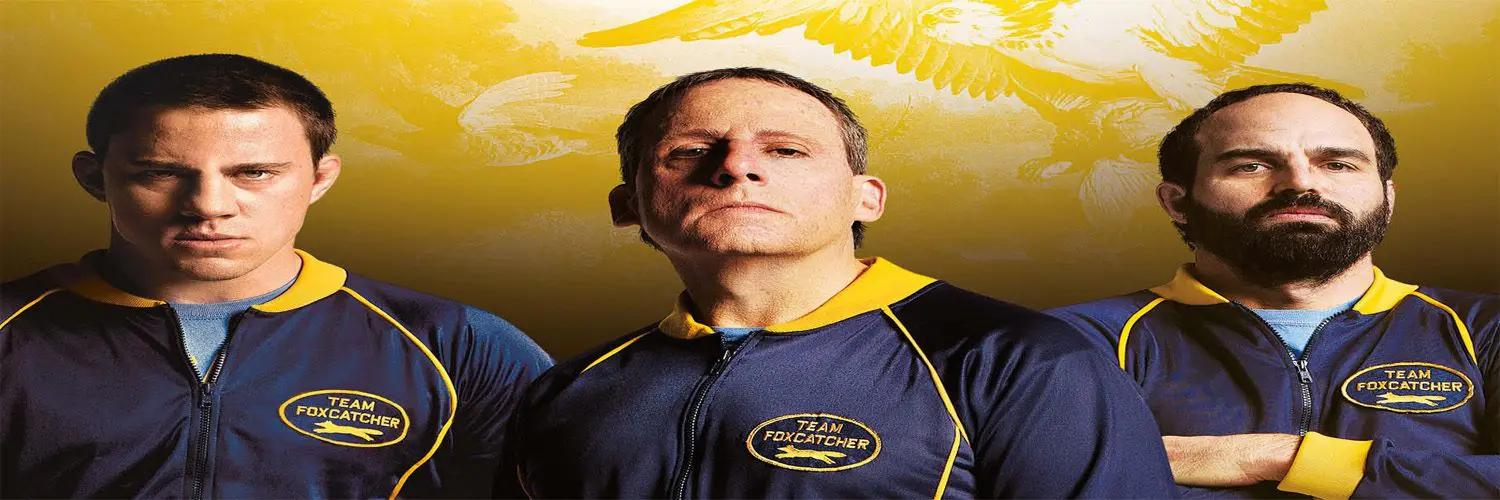

To lead “Team Foxcatcher”, du Pont coerced Mark and Dave Schultz (Channing Tatum and Mark Ruffalo), two former gold-medallists, into living on the farm and training the Olympic hopefuls.

Foxcatcher looks to hone in on du Pont’s unique, oddly banal psychosis, and the various unusual ways it manifested in the several years between the formation of Team Foxcatcher and the tragedy it would eventually come to be synonymous with.

As a sports movie, Foxcatcher is antithetical. Scenes of actual competition are few and far between; none are glorified or triumphant. There is minimal dramatic assistance by music unless it’s a sharp note of dread.

READ: Six Alternative Wrestling Movies

This is less a movie about wrestling as it is one about men who happen to be wrestlers. Professional competition is not the point of the story, but one of several intensely masculine spaces within which men – particularly damaged men – can be seen to relate to one another. Wrestling is the conduit. Through it, psychoses flicker and spark like live wires.

Du Pont, for instance, is fixated on wrestling as a means to differentiate himself from his socialite mother (who at one point describes the sport as being “low”), and due to an implied repressed homosexuality.

Insinuation is as far as the movie goes, but it’s hardly a subtle point. Late one night, du Pont wakes up Mark for a late-night practice that is really just the old man writhing and thrusting on top of the young one. In another scene, Mark is crouched at du Pont’s feet, like a pet.

The Schultz brothers express through wrestling a wordless understanding of and attachment to each other, which we later learn is deeply-rooted in shared childhood trauma – they pretty much raised each other in the absence of their parents.

Despite this closeness and their mutual sporting success, the two are drastically different. Dave is arguably more likeable and inarguably more functional; he’s happily married, a father, and a successful coach, whereas Mark is single, dim-witted and burdened by intense self-loathing.

We’re introduced to him as he ekes out an existence in the long shadow cast by his brother, living alone in a tiny apartment, training alone in a decrepit gym, and giving lectures to bewildered school children about how he won his gold medal. He’s vulnerable and malleable, which multi-millionaire du Pont is able to exploit (along with an all-too-true example of class-based ignorance) in order to recruit him as Team Foxcatcher’s head coach.

In du Pont Mark initially sees a father figure, a less overbearing older brother, a boss and a friend all at once. The movie is smart enough that you understand du Pont’s appeal to him.

Mark is willing to overlook du Pont’s various neuroses just to preserve his position as the focal point of someone’s life. He’s spent so long living and training alone that he’s enraptured by the idea that someone would value his talents.

The essential flaw in his thinking, of course, is that du Point doesn’t value anything about him other than the characteristics he’s trying to appropriate. As a scion of once-great men in his inherited corridors of power and privilege, du Pont’s monomaniacal fixation on wrestling is an avenue through which he believes he can restore the honour and tradition of American masculinity and patriotism.

But the fact he’s really just a garden-variety nutcase in a psychological tailspin means he’s unable to really grasp what any of his outdated ideals and pioneer machismo actually mean. Outside of his affection for Americana, he has no real understanding of what it means to be a great or even good man by the standards of the culture he so desperately seeks to embody.

And because he cannot succeed as an athlete like Mark and Dave have, or as an innovator like his ancestors once did, he instead attempts to use his wealth and psychological terrorism to buy and control those who can. It’s probably not a coincidence that he stores Mark in a cottage that also contains a full taxidermy case.

Mark is particularly empathetic because he clearly sees this, and yet is unable to separate himself from du Pont until he has already been irreparably damaged by him. Channing Tatum lends the role his distinctly likeable aura, but also an almost childlike vulnerability – a particularly difficult quality to imbue in a character that also has to be credible as an Olympic-level wrestler.

Likewise, Mark Ruffalo, here a bearded, balding bear of a man, turns in a surprisingly tender and layered performance as Dave. In perhaps the film’s best scene, his character is interviewed as part of a laudatory video extolling the virtues of du Pont as a leader, athlete and patriot, and Ruffalo’s hesitant, modulated responses are perhaps the most excellently squirm-inducing acting committed to film in 2014.

How does Steve Carell perform in Foxcatcher?

Most notable, I suppose, is a nigh-unrecognizable Steve Carell playing extremely against type as John du Pont. Carell is a great comic actor, but one imagines he doesn’t frequently foray into dramatic territory for a reason. Not that he doesn’t often come across as incredibly chilling, but that he just as often tends to oversell the role in such a way that it borders on parody.

It doesn’t help that the makeup intended to serve his performance is so distractingly poor (the nose is a different texture and coloration to the rest of his face), or that Miller has him use it in such obvious ways.

He cuts an absurd figure, and his more obvious eccentricities – asking his “friends” to call him “The Golden Eagle”, or actually taking part in the (fixed) over-50s wrestling category – are almost damagingly humorous.

Outside of that odd, almost turkey-like physicality though, Carell has the real du Pont’s halting, nasal speech pattern just right, and a lot of the more broadly horrifying things he says and does are also the most reserved.

He’s at his best when the screenplay allows him to be quietly exploitative, though some important context is only alluded to with a single throwaway line. In the late 80s, at the tail end of the Cold War, U.S. wrestling was in dire straits, severely lacking the necessary support and funding to properly remunerate the athletes who dedicated much of their lives to representing America in the sport.

To people like Mark and Dave, du Pont being willing to essentially create a hub for freestyle wrestling was a huge deal and a significant part of the reason why the brothers – latterly Dave in particular – were willing to shelve their integrity and principles.

Foxcatcher doesn’t overlook these details; it just treats them as the subtext of the eventual crime rather than a fundamental component of why it was able to take place. To the movie’s credit it never really seems interested in being anything other than a stark presentation of the facts.

It never tries to moralize or rationalize du Pont or his actions, merely acknowledges that they happened. It’s frank, and in turn very effective and unsettling. But this kind of context is important, and it could have been included without anything else being lost.

Where Foxcatcher is most insightful is in its depiction of du Pont’s gradual realization that he cannot purchase and own people the way he can ornithological texts or extraordinarily rare stamps.

While it is ostensibly a film about male self-identity, at its heart is really a story about an insanely rich and lonely man who committed terrible atrocities for no reason other than he was crazy.

As a subtle actor’s showcase Foxcatcher is undeniably a triumph. Every frame is dripping with sincerity and an almost palpable sense that something awful is approaching. But du Pont is too enigmatic a figure for the filmmakers to unpick, and so we’re left with a slight air of frustration when the closing credits roll.

This is not a story which is wrapped up in a neat little bow. Really, it has no resolution at all. In life, many things remain unresolved though, and a courtroom conclusion or an assurance that justice had been served would not have remedied the damage caused by this bizarre tragedy. That these things leave us feeling sad and frustrated might even be the point.

More Stories