Summary

A Cure for Wellness is cripplingly self-indulgent, much, much too long, the narrative doesn’t hold up to even a cursory examination, and it’s just about the most depraved thing to have been bankrolled by Hollywood in recent years.

A Cure for Wellness is an old-school, Lovecraftian gothic horror picture that comes directly from the addled mind of Gore Verbinski – and Christ, you can tell. It’s wildly ambitious, the production design is immaculate, the visuals are remarkable, it’s cripplingly self-indulgent, much, much too long, the narrative doesn’t hold up to even a cursory examination, and it’s just about the most depraved thing to have been bankrolled by Hollywood in recent years.

It’s a movie I expected to mostly like and ending up mostly hating; a true love-it-or-hate-it marmite experience, albeit one in which the marmite is swimming with eels and being forced down your throat by a mad scientist.

A Cure for Wellness Review and Plot Summary

The mad scientist here, Dr. Volmer, is played by Jason Isaacs, and he’s the demented director of an alpine sanatorium built on the cremated remnants of a spooky castle. There’s a pleasantly occult reason for the fire-and-pitchforks peasant uprising that immolated the old residence a century prior, but I’ll leave you to discover that on your own.

These days, Volmer runs the place as an exclusive wellness centre for overfed corporate bigwigs who’re attracted to the miraculous restorative properties of the clinic’s aquifer-fed water supply. Funnily enough, everyone still looks ill.

That includes Lockhart (Dane DeHaan), a young Nicorette-chomping Wall Street stockbroker who looks as though he’s only moments away from finalising the biggest financial deal of the century or dropping dead at his desk.

With his sunken eyes and twitchy demeanour, he’s in dire need of a spa day – which is just as well, because the executive board of his brokerage firm despatch him to Switzerland in order to retrieve their CEO, Pembroke (Harry Groener), in time for a lucrative merger.

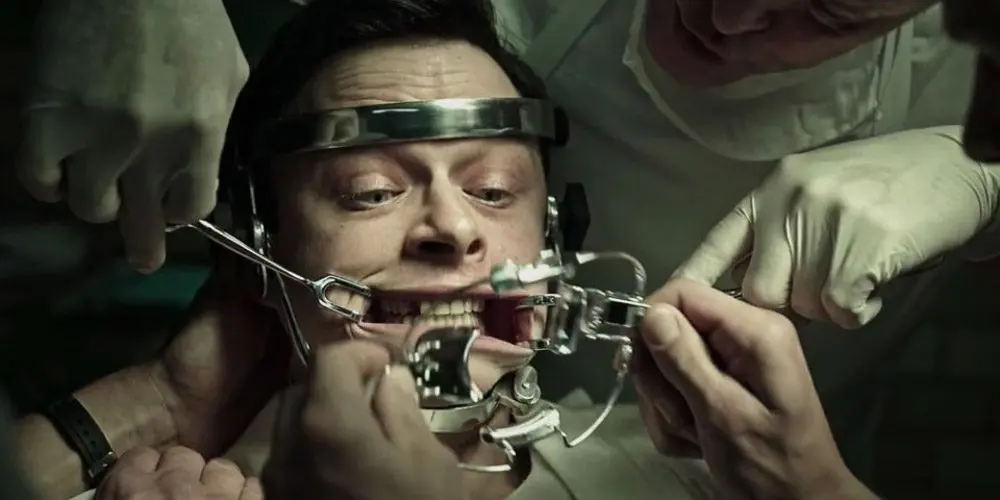

Lockhart has his teeth fixed in ‘A Cure for Wellness’ (Image Courtesy of 20th Century Fox)

Lockhart is an irritable irritant, and you have to imagine Verbinski and his co-writer, Justin Haythe, are aware of this. Why else, when he arrives at Volmer’s insidious retreat, would he sign a document without even glancing at the fine print? He’s too busy climbing the corporate ladder to trouble himself with whoever’s beneath him; he half-listens, half-looks, half-cares. Doesn’t seem to notice that all the resort’s staff seem cultishly devoted to their cobalt vials of the famed water, which Lockhart necks a tall glass of without much fuss. He’ll be gone soon, after all.

Needless to say, he won’t. A freak car accident prevents him leaving, and a badly broken leg keeps him hobbling on crutches (this is a smart suspense device that reminded me a little of the wheelchair-bound heroine from 2014’s mediocre Jessabelle). Now he needs to unravel the institution’s whats, wheres, whos and whys: what’s up with the water? Where’s Pembroke? Who’s the spaced-out young girl (Mia Goth) moping around the grounds? And why has everyone, including Lockhart, been diagnosed with the same mysterious illness?

You know there’s something in the water. Verbinski opens with a scene in a Manhattan skyscraper, where a stressed-out office worker takes a drink from the water cooler and thuddingly keels over. The camera lingers on the burbling liquid long enough to let you know that Verbinski’s eye for obvious symbolism is still wide open. A Cure for Wellness is amphibian.

A scene from ‘A Cure for Wellness’ (Image Courtesy of 20th Century Fox)

The high-rise false start seems unnecessary, and a less effective opening than the ominous, winding approach to the hilltop sanatorium would have been. But if A Cure for Wellness yearns to be anything besides unpleasant, it’s a capitalist critique.

And how better to address the morally-bankrupt fantasy of wealth and power than to shoot New York’s financial sector as a foreboding warren of glass-and-steel edifices, all canted and lopsided; bleak, drab, soulless.

Any detours here are crawling with European actors, and there’s not a conscience between them. You see the overweight residents of the spa swim idly through green-tinged pools, and you’re reminded of the automated lifestyles lived by the residents of Axiom in Pixar’s Wall-E. And you get the sense that a charismatic maniac like Volmer could convince these people of anything, so long as it cost enough to seem enticingly exclusive.

Is A Cure for Wellness a good movie?

The problem, from a storytelling perspective, is that it’s difficult to care about these people. That might be the point. But if it is, you have to ask why the movie exists. It deprives us of a sympathetic lead and then expects his squirm-inducing comeuppance to move us.

The most giddily violent sequences – in particular, a bit of impromptu dentistry – hold on for longer than you expect; show more than they need to. But you mostly feel like Lockhart deserves it.

This is a guy who barks at orderlies and asks his secretary to pick up a birthday present for his mother. He’s unscrupulous and, in his own way, a little unhinged. The irony is that the shark wants to escape the pool, but the reality is that you couldn’t care less if he drowned.

It doesn’t help that the movie’s mysteries aren’t particularly mysterious. The centre might be blessed with stunning snow-capped vistas, but there’s no coyness about its malevolence. The story twists and turns, and sometimes lurches, but never enough to truly sicken or disorient anyone.

There’s a vague pleasure in piecing together the layers of history, tracing the outlines of various nightmarish steampunk devices and wondering what they mean; which modern ill they’re intended to “cure”. But the paths all converge at a destination that feels as hokey as it does perverse. The journey is better than the destination, but the journey isn’t one worth repeating.

RELATED: