Summary

“Innocence and Panic” offers an insightful, powerfully grounded look into a seemingly “normal” marriage, even if it’s clearly aimed at critics rather than audiences.

There’s an accusation that often gets thrown around that certain pieces of art are designed for critics rather than audiences. It usually applies to stuff that is obnoxiously ambiguous, such as, say, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, but sometimes you find it being leveled at stuff like Malcolm & Marie, which for the most part is just dialogue-driven. (You could also make a case that film is explicitly anti-critic, actually, but that’s neither here nor there.)

The point is, film and TV being made “for critics” isn’t new, and neither is people calling it out for such, accurately or otherwise. Hagai Levi’s Scenes from a Marriage, a remake for HBO of Ingmar Bergman’s 1973 television miniseries of the same name, feels like it has been made for critics.

Even I’m not sure what that necessarily entails, though it’s a feeling I had all throughout. The entirety of the first episode, titled “Innocence and Panic”, is basically a series of protracted conversations between a couple whose happiness or even contentedness is difficult to get a read on. It’s intended as a snapshot of a believably “real” relationship, but for me the efforts in that regard made it feel ironically performative. The effect isn’t helped by the episode being bookended by meta flourishes detached from the show’s fiction; it’s a reminder of the artifice.

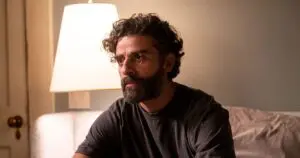

I never forgot, for instance, that Mira was really just Jessica Chastain (Molly’s Game; It Chapter Two; Ava), who plays her pent-up anxiety and tamped-down feelings like she’s the cork in a bottle of champagne. Likewise, her husband, Jonathan, an academic and stay-at-home father to their daughter, Ava, is Oscar Isaac (Star Wars; Annihilation; Dune; The Card Counter) with the frayed appearance of a sleepless college lecturer.

There are quirks to their relationship – she’s the breadwinner, and she’s sending sneaky text messages in the upstairs bathroom; he defines himself as a 41-year-old Jewish asthmatic like he’s toking on Chekov’s inhaler – but they’re both making such an effort to feign normality and happiness that you start to think maybe everything really is as it seems. An early interview with a psychology grad student who wants to use their decade-long relationship as a study of monogamy and gender norms feels like it’s leading somewhere more telling.

It’s mostly just an excuse for Jonathan to reject the student’s hypotheses.

If nothing else this scene gives us an idea of how they both see the institution of marriage. Jonathan’s take – Mira seems happy to let him do the talking for both of them – is interesting, since he mostly sees it as creating a stable framework for self-improvement. It’s a very specific type of man who sees the most overt symbol of the union between two people as the jumping-off point for individual progression. He doesn’t seem dismissive of his wife in a dangerous way, just an arrogant one; he hasn’t stopped to consider that she could ever feel differently than he does.

Mira and Jonathan are friends with another couple, Kate and Peter, though it’s hard to tell whether their comparative lack of stability is intended to make the other two seem happier or more boring. When they all have dinner and get drunk together, Mira doesn’t drink the toast, and later we find out why – she’s pregnant.

The revelatory scene feels truthful in concept – both want to figure out how the other feels before they confess their own opinion – but brutally put-on in its execution. I was eventually surprised when Jonathan finally plucked up the courage to say he wanted the baby, despite the additional pressure it would put on him being at home with two children, but that’s only because it’s a reversal of the usual gender roles. Mira doesn’t seem quite as enthusiastic, but eventually, both agree, if only because they both feel that’s exactly what a couple that pretends to be as happily married as they are would do.

In the very next scene, Mira is having an abortion. Time has passed, we’re to understand, but we never saw any of it elapse, so it feels a bit like there’s a scene missing. It’s still bold, in a sense, for a mainstream drama on HBO to depict abortion so frankly, as a legitimate medical decision made between two successful professionals after an honest appraisal of their circumstances. But that’s the problem with Jon and Mira – they make all their innermost feelings feel like admin. He clearly doesn’t want the abortion; she has resigned herself to it, but it’s hard to tell whether she wants it or not.

It takes a good while of fussing back and forth between vending machines and nodding politely along as the doctor lists side effects for Mira to finally pluck up the courage to tell Jonathan she wants to be alone with her grief for a moment. He’s happy to give her the space. He’s happy to give her everything, except perhaps the truth of how he really feels.