Summary

Girl Taken is an unconventional, slow-burn thriller that builds a story around the psychological implications of its grim premise instead of just the cat-and-mouse tension.

I’ve often wondered why Alfie Allen (Night Teeth), pays his agent, since nobody seems to be cast as feckless creeps with more consistency than him. At first blush, Paramount+ original Girl Taken doesn’t buck that trend, but appearances can be deceiving. Sure, Allen’s once again playing a deplorable sort here, but it’s a real, meaty character, and he’s chillingly good in the role across six slow-burning but psychologically complex episodes.

Based on the 2016 book Baby Doll by Hollie Overton, this is, on paper, a relatively straightforward thriller. A teenage girl is suddenly abducted by her English teacher, leaving her twin sister and mother behind to try, alongside a couple of coppers, to figure out what happened. But things get weird from there. Huge chunks of time elapse with alarming speed, and the story continues to shift in and out of different modes. The kidnapping and early search give way to something resembling a deeply uncomfortable domestic drama, and then everything morphs again into a manhunt, a court case, and a surprisingly nuanced portrayal of how loss and trauma ripple through an entire family.

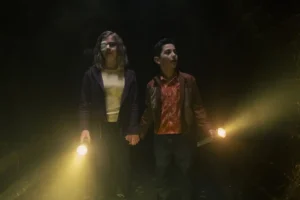

Lily and Abby (played, rather brilliantly, by twins Tallulah and Delphi Evans) are initially at odds. As 17-year-olds with very different social circles, interests, and temperaments, they often clash, and it’s an argument between them that leads to Lily walking home alone. A seemingly helpful lift from English teacher Rick Hansen (Allen), whom Abby has a fondness for, leads to Lily being snatched and imprisoned in the basement of a rural cottage where he pretends to his wife, Zoe (Niamh Walsh, Good Omens), that he’s writing a novel. And there she remains for several years.

Girl Taken makes a ton of very smart decisions. It uses Rick’s obvious grooming of Abby as a fake-out, since he ends up taking her sister simply because it’s more convenient. It uses the passage of time to indicate the kind of violence – sexual and otherwise – that Rick has committed against Lily without having to sordidly detail it on-screen. When we rejoin her in the basement a year after her disappearance, and she’s swollen with child, it doesn’t take Hercule Poirot to put two and two together. It allows Rick’s treatment of Zoe, and certain errant details and lines of dialogue, to form a picture of their relationship and his past without anyone having to, say, walk into a room with a file and read out a bunch of exposition.

The effect makes for a slower pace but a richer overall impression. The world feels lived-in, both before the kidnapping and after, and you’re consequently able to understand how certain things have happened in the interim, even though we didn’t see them develop ourselves. Abby, for instance, dwells in her grief over what happened, and gravitates first to drugs and then to Lily’s well-meaning boyfriend, Wes (Levi Brown). The girls’ mother, Eve (Jill Halfpenny), retreats into alcoholism, but we rarely see her drinking or being histrionically drunk; her dependency is largely implied, but Halfpenny’s performance highlights the gradual decline in thoughtful, grounded ways. Similarly, Zoe’s burgeoning suspicions about Rick, and her inability to confront them due to the grooming and abuse – a subtler variety than what Lily is subjected to – that she has suffered is very smartly done.

But the MVP is, somewhat unexpectedly, Alfie Allen, who plays Rick in a strikingly restrained way, only rarely ever indulging in over-the-top cartoon villain theatrics. I’m not sure I buy Allen as the kind of swaggering teacher that several students playfully refer to as “Mr. Handsome”, but he’s extremely convincing as a shrewd manipulator who shifts his demeanour to satisfy certain targets. His interactions with Eve and the authorities when he’s pitching in on the search for Lily are very different from his coercive control over Zoe, whose attachment to him for a while seems mysterious until an errant line of dialogue in the back half sheds some light on why she’s so dependent on him. We’re only in January, of course, so we must resist the allure of hyperbole, but it wouldn’t surprise me if this low-key ended up being one of the better bad guy performances of the year.

But as much as Allen stands out, Girl Taken boasts impressive performances and details everywhere, and it’s bold, especially in its back half, to shift from being a thriller about a young girl in captivity to being about a young girl who has escaped from captivity – that isn’t a spoiler; it’s central to the narrative – and now has to ingratiate herself back into a family and a community that have been deeply scarred by her absence. The final few episodes interweave legal thriller with fraught domestic drama to thought-provoking, often tender effect, and the show deserves real credit for not being content to just be a thriller. It works as one of those too, though.

RELATED: